This is a note from the The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Check out the previous installment.

In the next few installments, I’m gonna continue writing about my family’s early Soviet history — this time concentrating on my father’s parents. To start, I want to publish a kind of summary outline that my uncle Mikhail, who now lives in Israel, wrote up a few years ago detailing what he remembered about his father’s (my grandfather’s) life. His notes span the time from when my grandfather was born in 1909 in a village near Tambov to when he died as a result of a botched hernia operation in a hospital in Kingisepp in 1967.

My grandfather Aaron Moiseevich.

I gotta say, reading about my grandfather’s life — and by extension the life of my grandmother and my father’s early childhood years — it is downright depressing when laid out in the unemotional factual style that my uncle Mikhail employs.

Aaron, my grandfather, was a true believer in communism. He had joined the komsomol early and was active in Yiddish Bolshevik circles — “cells,” they called them — in Ukraine in his youth. From everything I know he was a kind and earnest person, and he got fucked for it in his long career of serving the state — beginning with him being banished to a crappy job when he was fifteen because he had criticized his komsomol superior.

And it was all downhill from there.

He got sucked into working the prison camp system as a political officer — first with Japanese and German prisoners of war, and then with regular Soviet convicts — working and living in log cabins in primitive frontier surroundings in the harshest, most remote reaches of Siberia. That’s where he spent most of his adult life, and where my father and his siblings spent their early childhoods.

I remember reading somewhere that to be stationed in a faraway labor camp was itself a kind of softer prison sentence or exile — not just for the individual, but their family, too. And that’s what this chronology reads like — like a chronicle of someone sent into exile. His life was better than the life of a convict but not by much. After his retirement, he was not allowed to go back to Leningrad but had to settle in a small industrial town 100 km away. Ex-cons faced similar restrictions on where they could live.

So yeah, this might be the most straight depressing grandparent story I have. Working on it has made me understand my dad’s anticommunism a lot better. His father had a grim life and a grim death. He — along with his wife — were true believers. But they still got ground up and spat out by the system. And it wasn’t clear to him what it was all for.

My dad Boris and other camp kids outside the labor camp’s fire station. The year’s 1956. He’s the one with the cap — second from the right. Nizhnyaya Poyma, Reshety station.

It’s not all horrible, obviously. My father remembers the wild nature of Siberia that he got to experience as a small child with fondness. And my uncle remembers some weird and touching moments, too. Like the time railroad operators cleared the tracks to let his family leave the camp:

In 1957, my father retired. In his many years of service, he had several government awards. That summer he was supposed to leave his post at the camp, there appeared a problem: he needed to get approval from high authorities to clear out all the cargo railroad cars that were parked on a branch of the railroad that led out of the taiga and linked up the main federal railroad line. To get this approval delayed his departure. So the railroad management there, in violation of the rules, agreed amongst themselves to open up a path for our family to the main railroad line and moved all the parked train cars into dead-end branches: “the major is leaving for retirement!”

Anyway, I’m reprinting my uncle’s chronology blow. I translated it from Russian.

—Yasha Levine

I am Mikhail. My father — Aaron Moiseevich — was born on May 13, 1909 in the village of Shaposhnik in the city of Tambov.

1909-1924

My father’s parents were Moisei and Sofia. In addition to my father, they had two daughters and a son.

Before the revolution, the governor of Tambov deported all the Jews from the city. So the family settled in Ukraine — according to my father, in the city of Glukhov, which is where he spent his childhood.

In 1924, at a komsomol meeting, he criticized the secretary of the city’s komsomol committee for shirking his work duties. For this he was punished — and sent to work as a representative of chemical artel on the outskirts of Glukhov.1 He was 15-years-old.

In the artel, they didn’t have enough boilers. So my father traveled to procure some in Leningrad. He bought and shipped them to his artel. He had some help from relatives who lived in Leningrad.

Young Aaron in the Komsomol. That’s him bottom row, first from the right.

1930-1936

In 1930, being already a member of the VKP(B)2, he was accepted into the RabFak.3 He was not allowed to finish his studies at the RabFak. Insteadn, in 1931 my father was drafted into the army — into a sapper battalion stationed in Pskov, where he was elected as the battalion’s Party Bureau secretary.4 Because he was a soldier, his election into the Party Bureau gave him some privileges. He was allowed to live in a rented apartment, rather than the barracks. And for his personal weapon he was given a Nagant, rather than a rifle.5

Before he was demobilized from the army, in 1933, my father was transferred to Leningrad — to the PolitOtdel, where he was offered the opportunity to study at a military-political school. It was impossible for him to decline. If he did, he’d have to give up his party membership.

During his studies at the school, he married Anna Perlova. In 1935, I was born — in the city of Leningrad.

After finishing the military-political school in 1936 my father was sent as a politruk to a military base in the Transbaikal Military District (Lesnaya station, 60 km. from Chita).6 He moved there with his family and was elected as the Party Bureau secretary of his company. In Chita, in 1937, my sister Larissa was born.

1936-1941

During the mass repressions of 1937, an NKVD official ordered the secretary of the komsomol to spy on my father and to report on his activities and conversations, threatening him that if he refused to carry out this order he’ll be sent to jail or a labor camp.

My father found out about this and he went to the head of the Operational Department of the Transbaikal Military District to ask him about the justification for this order.7 As a result, the head of the Operational Department of the Transbaikal Military District gave the NKVD official a serious reprimand and the issue was resolved.

There were two other dangerous incidents:

— When General Levandovky (who had the same last name as my father, but was not related; he was Polish by nationality), the commander of the Far Eastern Military District, was repressed, my father was interrogated by the NKVD: was he related to the arrested general?

— Syrovaiski, a general of Engineering Troops, was arrested and shot in Moscow. His wife was my father’s second cousin, was sentenced to 10 years. My father was certain that his family ties to the general would eventually lead to him and prepared himself for arrest. Because people were usually arrested at night and grabbed ”from their beds” in their underwear, my father didn’t want to suffer that kind of humiliation. So he spent a whole year going to sleep not taking off his clothes, in his military uniform. Eventually the Syrovaiski family was rehabilitated — after the general’s death. His wife had her Moscow apartment returned to her.

In 1941, my father was transferred to Chita. His position was senior politruk of a company stationed in the Transbaikal Military District — now with the rank of “capitain” — in a settlement by the name of Antipikha (6 km. From Chita). He was an assistant to the commander in charge of the political section of made of soldiers recovering from their wounds after coming back from the front.

1943-1946

In the autumn of 1943, my father was transferred to the 235th Infantry Division (Transbaikal Military District, Solovyovsk station — on the border with Mongolia) — to the Medsanbat battalion there.8 He was assistant to the commander in charge of the political section. He served there until August 1945. In August 1945, his division advanced to Manchuria through Mongolia to fight against the Japanese Army.

After Japan’s capitulation, his battalion was sent to Antipikha and disbanded.9 Shortly after, the battalion was reformed and (for those with families — including our family) was sent to guard a Japanese prisoner of war camp (101 km. From the city of Tayshet in Irkutsk Oblast).

The Japanese prisoners were put to use laying down gravel for the construction of a railroad. Before the war this was carried out by regular convicts.

When his division left for Manchuria, an auxiliary support division (in short, a diary farm) was left abandoned. The officers’ wives took it under their control. Because my mother was the only woman there who knew how to work with cows she was elected as the head of the dairy.

My mother had been born 1910 in Ukraine in the city of Konotop.10 Her father was a tailor.

During the first world war, German troops occupied parts of Ukraine. During the civil war, power in the city changed many times: reds-whites-bandits. My grandfather — Abraham Solomonovich Perlov — and his whole family were saved by his profession as a tailor, but not always. Sometimes they had to hide from the new “masters” in the basements of their relatives in the village.

After the formation of the USSR, my mother joined the komsomol. She worked as a sales clerk and a machinist at the Kharkov Tractor Factory, and at the end of the 1920s moved to Leningrad and found a job at a housing maintenance office. There she was given her own small — 10 square meters — room.11

In 1931, she became a candidate for the VKP(B) but was accepted as a member only in 1939. That’s because during the times of the repressions new membership into the Communist Party were held up.

1946-1949

Then in the spring of 1946 a part of the battalion that was guarding the Japanese prisoners of war was demobilized — and that included my father. Our entire family — me, my parents, and my sister — moved to Leningrad and lived with our relatives. A few months later, my father found work as an instructor at the political department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.12 This was in Kohtla-Järve, Estonia. That summer he was transferred to serve as deputy to the commander of a prisoner of war camp in Kiviõli, Estonia.

In 1949, German prisoners of war began to be returned to Germany. My father was involved in work with the German Antisfascist Committee to filter out prisoners who had been members of the SS and Gestapo and who then were sent to a special camp.

In Estonia my brother Gena was born. Sadly he didn’t live very long — about two-and-a-half years. He came down with a serious flu. It was a bad case. He went to the hospital and — shockingly: the hospital didn’t have any oxygen.

1950-1952

After the liquidation of the German prisoner of war camps, my father was transferred to Krasnoyarsk Krai to a settlement named Sora (Erbinskaya station).13 He was the deputy commander for political affairs at a militarized detachment guarding inmates at a labor camp where they mined molybdenum. By this point he had achieved the rank of major.

At Sora, my family lived for a year. Conditions there were not easy. The first couple of months all the families — about forty people — lived together in one room, in a community center.14 Later we got one small log cabin without a roof for two families — ours and that of a road engineer. Each family got one room and we shared a kitchen. Half a year later we moved to an apartment in a building that was being constructed.

With food — like everywhere in those years — it was bad. A cow that was purchased helped a lot. Thanks to it we had milk, sour cream, cottage cheese, butter, fermented milk, and buttermilk. Thanks to these milk products, my father was able to cure his stomach ulcer (medicine had not helped).

There was a school in the settlement where I went to school (7th grade) and my sister (6th grade). There I was accepted into the komsomol.

In 1950 my father was transferred to a geological exploratory expedition as a deputy for political affairs in Nizhneangarsk (Usovo).15 The expedition was involved in measuring iron ore reserves and was under the control of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

People manning the drilling rigs, driving trucks, and working in laboratories — along with free workers, there were also former inmates that had already served out their terms, both political prisoners and criminals. After serving out their sentence, they were exiled and were not allowed to move more than 60 km from where they lived.

In Nizhneangarsk we spent two years. Me and my sister went to school in a settlement named Razdominsk (35 km from the expedition site), where we rented a room. During this time, my mother worked as the head of the expedition’s cultural club and helped people who were trying to add something cultural and spiritual to a difficult and mundane situation: a painter (Godlevskii), a singer (Baklina), a violinist, some actors. My mother was able to provide a material base for a theatrical production: costumes, materials for the set decorations, paint, and other things. She also tried to make things easier for people. For instance, she was able to get the violinist transferred to job that would not stress and ruin his fingers and hands.

There was a small orchestra that performed in the club once a week. I was a tenor in this orchestra.

There was a group of exiled officers who had been prisoners of war.16 They organized a volleyball team. I played on this team and we played against other teams in different settlements — within 60 km.

On this expedition, among the exiled workers, were famous specialists:

— Naval commissar (Lentovskii)

— Moscow prosecutor (Angelopulo)

— A general and artillery specialist who continued to produce works on ballistics.

The absurdity of the convictions of these people is exemplified in the story of the film engineer:

He had sent his film technology invention to BRIZ (Bureau of Rationalizations, Proposals, and Inventions) in Moscow.17 One of the bureaucrats there answered that this invention is not interesting to anyone, while himself taking it and selling the invention to foreigners. The NKVD convicted both of them. By sheer luck they both wound up in the same transfer jail and the former bureaucrat from BRIZ told the inventor the story of why he was convicted. The film engineer did not tell the bureaucrat that he is the inventor in this story, as he was afraid that the bureaucrat would kill him. When the film engineer wound up in exile, he told my father this story — and my father started putting together a petition for this man’s rehabilitation.

In Nizhneangarsk there were people who were not convicts but they had the same restrictions on movement. These were people who had been exiled from Western Ukraine, the Baltics, the Volga Germans, Greeks.

In 1951, when we lived in this expedition, my brother Boris was born. To give birth, my mother travelled to Krasnoyarsk, as she was already 42 years old and she was worried about complications during birth. The birth indeed turned out to be difficult. Doctors gave her a choice: save the life of her baby or save her own life. She told them to save the life of her child. Luckily, they both survived.18

My grandfather top row, first from the right. My dad the kid with the dark hair in the foreground. 1957. Labor camp. Nizhnyaya Poyma, Reshety station.

1952-1957

After the expedition, my dad was transferred to the Directorate of Labor Camps in Nizhnyaya Poyma (Reshety station) — to serve as deputy commander for political affairs for the militarized guard there. The work there was very difficult. My father was very proper and independent, he treated soldiers and convicts with respect and humanity — convicts respected him. For this his boss in the Directorate of Labor Camp took a dislike to him and made his life miserable in all sorts of way: he kept transferring my father form one post to another (once even to head the administrative-maintenance division, which was considered disrespectful for a person of his rank) and accused him of having improper contacts with inmates.

My mother, as a wife and a member of the communist party, complained about this constant harassment to party’s regional committee — she notified the secretary of the party in writing. They solved the problem and removed his boss, a colonel, from his post. His boss never returned to his old post.

In 1957, my father retired. In his many years of service, he had several government awards. That summer he was supposed to leave his post at the camp, there appeared a problem: he needed to get approval from high authorities to clear out all the cargo railroad cars that were parked on a branch of the railroad that led out of the taiga and linked up the main federal railroad line. To get this approval delayed his departure. So the railroad management there, in violation of the rules, agreed amongst themselves to open up a path for our family to the main railroad line and moved all the parked train cars into dead-end branches: “the major is leaving for retirement.”

The convicts at the camp told my mom: “There was one good man in the taiga, and that man is leaving.”

On advice of my dad’s colleagues, our family moved to the city of Kropotkin in Krasnoyarsk Krai and I was demilitarized to that city as well.

My father’s health worsened. He could not tolerate the hot southern climate and even lost consciousness several times. He spent a month undergoing treatment in the MVD’s Central Hospital in Moscow but it didn’t really help. He was officially categorized as an invalid — category three.19

My father was very sick all the years he spent in retirement. There was no possibility for him to get better, and in 1967 he died.20 My mother died in 1982.

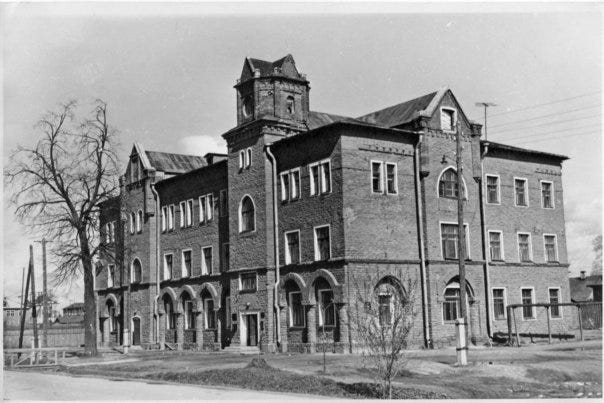

The hospital in Kingisepp where my grandfather died.

An Artel was a kind of worker cooperative that existed in Russia and then in the Soviet Union.

VKP(B) is an abbreviation of what was then the Bolshevik branch of the All-Russian Communist Party. The VKP(B) became officially Communist Party of the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death.

The RabFak — abbreviation of “Workers’ Faculty” — was an educational system that prepared workers for study in colleges and universities.

As I understand it, the secretary of the Party Bureau was meant to coordinate and oversee ideological work within the battalion. This role existed in most government structures — from small to large.

A Nagant was a Russian/Soviet revolver typically carried by officers back then.

Politruk is short for “political commissar” or “political officer” — someone whose job to make sure everything is done within proper ideological boundaries of the party. Chita is just north of the border with Mongolia.

Guessing that this was the Operational Department of the NKVD.

Medsanbat is short for a “medical sanitary battalion.”

Antipikha is a settlement on the outskirts of Chita.

A city in Sumy Oblast, northeastern Ukraine.

In a communal apartment.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs was basically the federal police force. It was spun off from the NKVD after World War II and oversaw, among other things, law enforcement, internal troops, prison camps.

https://gulagmap.ru/camp403

My dad explains: “It would be a simple building, probably even with a small stage for concerts and other events, mostly of political nature, and some rooms with simple entertainment, like chess boards, and for use as classrooms for propaganda gatherings.”

A settlement in Buryatia.

I’m guessing they were Red Army officers captured by Germans.

A patent bureau.

From my dad about his own birth: “A late-term abortion would have taken care of the problem. Although, at the time, abortions after 12 weeks were banned in the Soviet Union, barring special circumstances. But I think my mother's case qualified.”

The highest level of disability in the USSR.

He didn’t die of natural causes. He died from complications following an operation to fix his hernia. Apparently the surgeons introduced an infection into the wound…and that’s what killed him. He died in the town of Kingisep.

That is very depressing.. What a world we live in. Cant wait for the apocalapolis.

Your grand-parents were damn good communists, the kind all communists should aspire to be.

Thanks for this: it's a good tonic for the usual bourgeois triumphalism out there.