“Who am I? Well, I was born in Ukraine, so I am Ukrainian. But I am from the Donbas, and we’ve always been something different..."

The muddy issue of identity.

This is a note from the The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Check out the previous installment.

I wrote the other day about Russia’s invasion and occupation of Ukraine and the issue of national identity. For many it’ll almost certainly harden one way: towards a much firmer Ukrainian sense of self. For others, things might not be so simple…

The war — it looks like it’s gonna go on for a while. So who knows how things will shake out in the end. Being a Soviet Jew and an immigrant, I know firsthand that national self-identity is a weird fluid thing — a product of many forces, most of them outside of an individual’s control. In Ukraine today, I imagine some of those forces can be very basic. A lot of Ukrainians are gonna reject their Russianness for obvious reasons: Russia’s waging a war on them and killing their friends and family. For others things might be a bit mushier. They might identify as Ukrainian but also Russian and not feel the same antagonism for the Russian side. For them Russia might not be so bad — even if it had just leveled the city where they lived and forced them to go on the run. Russia is a place where they have family and friends, where they know the language and culture, where they can quickly get a job, find a safe place for their kids.

Fred Weir — a very good journalist who back in the day cowrote an indispensable book about the Soviet elite’s capitalist counter-revolution — has a short article in the Christian Science Monitor about Ukrainian war refugees in Russia. It gives a glimpse into the muddy issue of blame and identity.

While precise figures are difficult to come by, about 12 million Ukrainians are thought to have been displaced by the war, and as many as 5 million have left the country. Most have headed west, to European countries that have flung open their doors to take them in.

But about 2.3 million Ukrainians, mostly from the war-torn and Russian-speaking east, have arrived in Russia since late February, according to the Russian Ministry of Emergency Situations. Though the Ukrainian government, backed by the United States, alleges that many Ukrainians have been “forcibly deported” to Russia and subjected to various kinds of abuse, several war refugees, including Ms. Lyashova, and the volunteers who work with them, offered different accounts at an aid center run by the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow in mid-July.

Although most of those who seek refuge in Russia hail from the Russian-speaking parts of eastern Ukraine, it would probably be a mistake to view their choice as “voting with their feet” in some neo-Cold War sense, experts say. For many, Russia is just an enduring fact, familiar and relatively safe, and it’s possible for them to blend in easily.

“Almost every family in Ukraine has close friends or relatives in Russia. So many come to Russia because they have people here who can help,” says Mikhail Chernysh, an expert with the official Institute of Sociology in Moscow. “It’s not ideological. There can be political disagreements within families, even quite bitter ones, but they still help each other. ... Russia is big, it has demographic problems, and many regions have serious labor shortages. I know the logic sounds strange, but an influx of friendly population is welcome in many parts of the country. Russia has the capacity to receive them, offer opportunities, and it’s nothing to do with politics.”

…Several of the refugees interviewed for this story said prospects for returning depend upon whether the Russians will rebuild the shattered towns and cities they have fled from, and create prospects for a decent life. Few seem to care whether the government will be Russian or Ukrainian.

“Who am I? Well, I was born in Ukraine, so I am Ukrainian. But I am from the Donbas, and we’ve always been something different, not Russian, not Ukrainian,” says Ms. Lyashova. “I don’t know. I want to live in peace, with my family, to see my children grow up. If Mariupol is restored, of course we’ll go back there. It’s so hard to say anything right now. We just want to survive.”

It might be surprising that people who had their cities and apartments leveled by Russia would see Russia as safe haven, and not just as an evil that needs to be avoided at all costs. But then the politics of allegiance and blame and national identity in Ukraine are a lot more muddy that people here in America and Europe understand them to be.

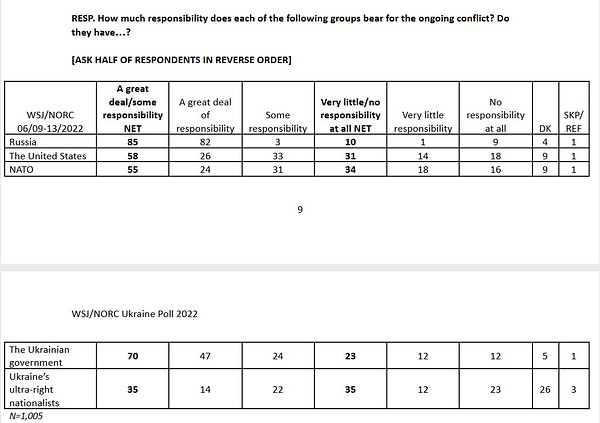

Reliable opinions-and-beliefs data is always hard to come by — and even more so when you’re dealing with a population at war. But it’s clear that many Ukrainians have a complex view of this war and its causes. For instance: A recent Wall Street Journal poll found that the vast majority Ukrainians blame Russia for the war — that’s not surprising. What is surprising, though, is that big proportions also believe the United Staes, NATO, the Ukrainian government, and even Ukrainian nationalists are to various-but-large degrees to blame as well.

But polling is polling, so you can trust it or not…

—Yasha Levine

This is a note from the The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Check out the previous installment.