The Personal is Political

The Soviet Union is long gone. But we Soviet immigrants continue to be useful tools — trophies that can be paraded around as living examples of American superiority.

This is the second installment of my intro to The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Read the previous segment: “Victims of Communism.”

After the Victims of Communism conference, I spent my free time figuring out how I would write my book about America’s various efforts to weaponize nationalism and its nationalistic immigrant communities.

I focused on the Ukrainian diaspora, a community that was most developed by American intelligence agencies. I looked at the scaffolding used to support the process — propaganda projects like the CIA’s Radio Liberty and even Radio Free Asia. I began working the archives, took a short trip to Ukraine to get into the mood, and started drafting a book proposal. The way I saw it, this was a true crime story — the story of a cynical, highly-classified plan to rescue European fascism, to nurture it, to inject it back into Europe and Russia, and to watch as it ratcheted up long-simmering ethnic strife and turned people against one another. I wanted to unravel the story like a detective thriller: Clandestine meetings with the enemy. Recruitment of sadists and mass murderers. Doomed commando missions behind the Iron Curtain. Soviet assassins prowling Europe. Defection and infiltration. Genociders enjoying quiet, respectable lives in America, while secretly living in fear of being exposed. American politicians in bed with Nazi collaborators.

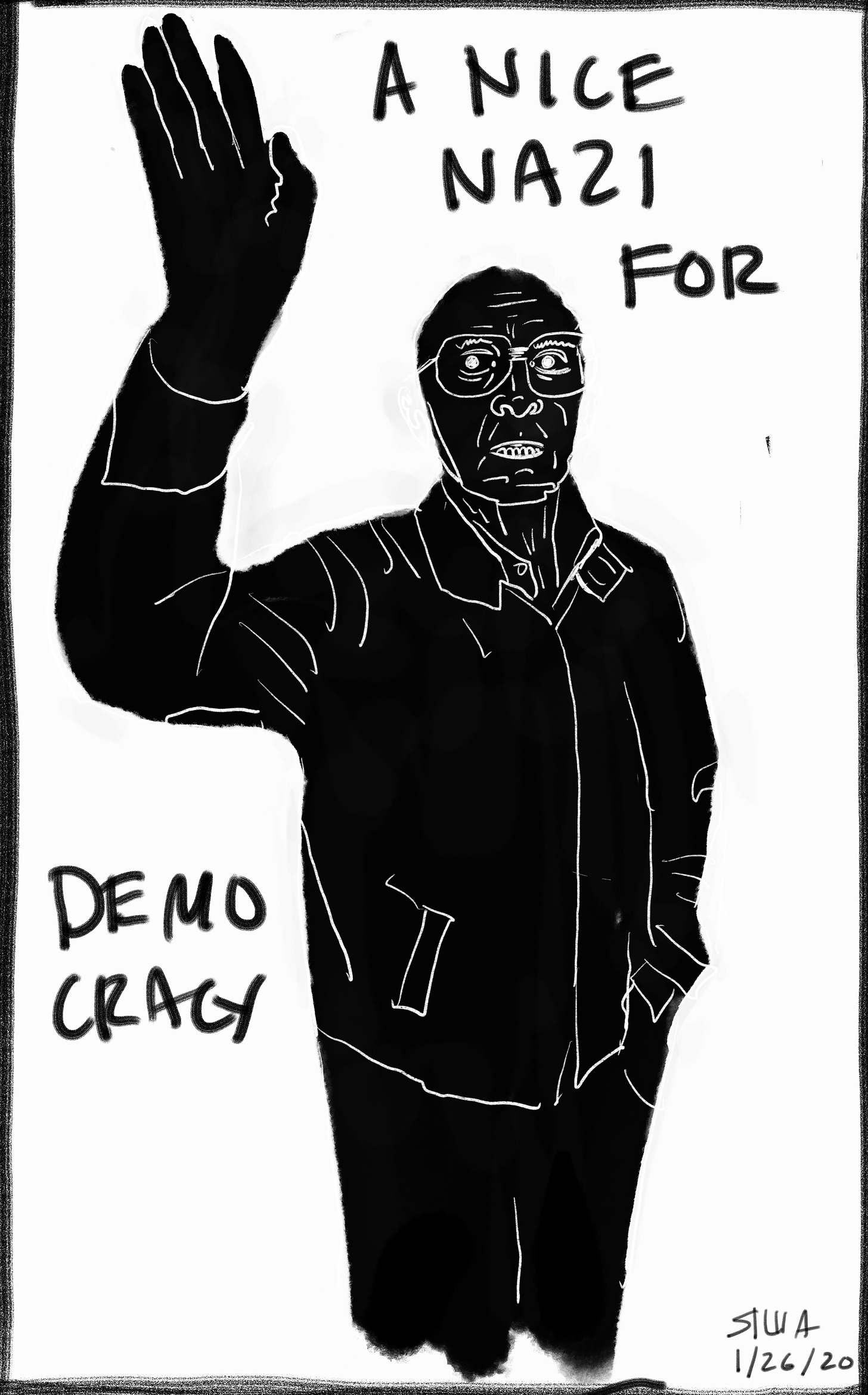

Mykola Lebed, weaponized immigrant and a true fighter for democracy.

But as I got into the project, my excitement for the original idea began to wane. It dawned on me that my hyper-focused interest in Ukrainian fascists and on Nazi collabo emigres and my grand plan of writing a Hollywood type Nazi crime thriller was a massive copout. There was cowardice lurking underneath. Here I was planning this big project to look into weaponized immigrants and yet I was keeping my own weaponized nationalistic immigrant community completely out of the picture.

Sure it was easy to get worked up about America working with cartoonishly evil Nazi collaborators — I mean, who doesn’t hate goose-stepping, genocidal Nazis? But it was a tricker to look at the much subtler weaponization of my own family and my own Soviet immigrant community for pretty much the same exact purposes.

Why had I avoided looking into it? For years — well into my 30s — I was in denial about my immigrantness, preferring to think of myself as just “an American,” as ridiculous as that may seem. Even when I started to come to terms with my identity, it didn’t really cross over into my journalism. Guess I didn’t want to deal with the personal and familial messiness of it all. Deep down in my subconscious mind I probably knew that if I went even just a bit into that direction, I’d have to go all in. I couldn’t do it casually or halfway. So it was much easier to look at Ukrainian fascists and Nazis. They existed outside of my own story, and the morality was black and white there. It was easy.

I had long been aware of the Cold War politics behind my family’s immigration to the United States. But for years it had been compartmentalized — existing in a space in my head all by itself. It took me delving into the Ukrainian Nazi collabo emigre question to connect the obvious, and to realize that my “being saved” from communism was part a larger program to weaponize nationalism — a program adopted by America after World War II to fight the Soviet Union and the Eastern Block. And as I put the personal and the historical strands of this thing together, I realized that my disembodied approach to the subject was absolutely the wrong way to do it. So I scrapped the original idea and decided to look at the subject of weaponized immigrants from a much more personal perspective.

My family in our finest clothes on a trip to Rome from our migrant camp in Ostia. 1990.

My family — my brother, mom, dad, and I — left Leningrad in 1989 when I was eight years old. We took off in a hurry with a bit of cash and one-way tickets to Warsaw, where my mom had to sell her mother’s jewelry so we could buy connecting tickets to Vienna. We spent the better part of a year in refugee camps — first in village in Austria and then in Italy, where we lived in a grimy trailer park by the name of “Castel Fusano” in the town of Ostia, just outside of Rome.

We left the Soviet Union as part of a huge wave of mass Jewish immigration that started in the 1970s and really blew up towards the end of the 1980s, when Mikhail Gorbachev finally whipped open the gates.

For most of the 20th century, American lawmakers had crafted laws to specifically keep Jews out. We were “rats,” according to Wisconsin Senator Alexander Wiley, who helped craft a 1948 law to prevent Jewish survivors of the Nazi genocide from immigrating to America, while letting in the very people that had carried out the genocide. Yet with us it was different. Suddenly Soviet Jews occupied a special, glorified place in American political culture. Americans protested outside Soviet embassies on our behalf. Some — like Meir Kahane’s people — even lobbed bombs. Lobbyists and lawmakers from Washington, DC championed our cause and put together sanctions to secure our release. We were a happy bipartisan project — supported by the might of the American Empire.

As far as immigrants were concerned, we were a very privileged class. The question is: Why?