The Newly Converted

Nativ’s nationalist mythology triggered something deep. It wasn’t a materialist thing. It was spiritual, closer to a religious awakening.

Chapter One of The Soviet Jew continued: Part III.

I’ll be dropping all installments into this table of contents going forward. Paid subscribers get full access to all chapters and footnotes and audio versions. Read the previous bit: “The Farmer Spy.”

The year was 1956. Moscow. Four years had passed since Israel launched Nativ.

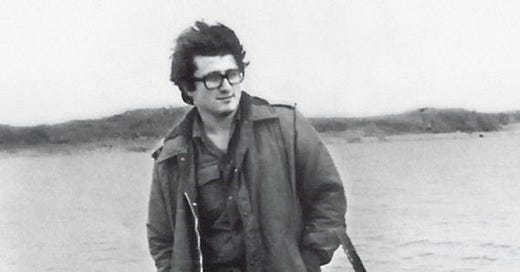

Yakov Kazakov, a 19-year-old engineering student who looked a bit like a young Brace Beldon, was headed to class with a Jewish friend of his to take an exam. “I have a pamphlet,” the friend said to him. “Maybe you’d like to see it?”

Yakov had thick black hair, a boxy jaw, and was always wearing his square-rimmed glasses. He took the pamphlet, looked at it, turned it over. It had a Hebrew calendar on its cover. Inside was some text and some pictures. Yakov flipped through the pages. They described what life was like in Israel and showed photos of young Jews laughing and enjoying themselves. To Yakov, it all looked very exotic. But the text in the pamphlet explained that there was nothing exotic about it at all. Israel was his historic homeland. These Jewish youths, people just like him, were home — his home.

Yakov was a typical assimilated Soviet Jew. A lot of his family came from Belorussia. Many of his male relatives died during the Great Patriotic War fighting the Nazis. His parents were both engineers, and he was following in their footsteps. He had been in the Komsomol, the Communist Party youth wing, and had recently joined the Party itself in order to help his career. He had never been religious, nor was he particularly tied to his Jewish identity. The most Jewish thing his parents did was speak a bit of Yiddish at home. And he had never experienced any real antisemitism — except maybe one instance when he was a child and Stalin had died and some kid at school said something about “the Jews” killing their great leader. But that was a minor thing, a bizarre brief event devoid of deeper meaning. Yakov’s Jewishness was never really part of his identity.

Yakov was a Soviet man — hopeful about a bright modern Soviet future. He had never thought about Israel before. But the pamphlet changed all that — it changed his life.

“I found it hard to be calm after that,” he later explained. “Everything that had been important to me until then lost all meaning. Apparently, all the emotions that had been building up inside me for years, ever since the first time I heard the word ‘Jewish’ applied to me with disgust, were bursting forth. Everything I had tried to repress and ignore, all the half-statements, the attempt to attach no importance to my Jewishness, all of these had been simmering inside me, waiting for the right moment. For the first time, I felt proud of my Jewishness and proud to be connected to the State of Israel. I felt, more than understood, that if I wanted to be a proud man, at peace with myself and my identity, I could only do so in the Jewish state. In any alternative, I would have to compromise with my truth and live a lie. The decision was made even before I fully understood it and all its implications. I no longer had any choice.”1

That little pamphlet hit Yakov like a lighting bolt coming straight from Mount Sini, rearranging his brain and turning him into a Zionist on the spot.

At the time, Yakov didn’t know that the pamphlet was no ordinary thing. It didn’t randomly appear in the Soviet Union. It was brought into the country through covert diplomatic means by agents of Nativ, the new clandestine security service that had been set up by Israel seed Zionism and facilitate a mass migration of Soviet Jews to the Holy Land.

Three years earlier, several families — including Nechemia Levanon — had moved to the Israeli embassy in Moscow. Officially they were posted there as agricultural attaches. But this was just a flimsy cover for their real mission: to travel the country and engage in surreptitious outreach to Jews around the Soviet Union. In short: they were there to proselytize Zionism.2

These agents went whereverJews were — to big cities and out to the provinces. They handed out Zionist literature, talked up the greatness of Israel, collected names and phone numbers, and gathered intelligence on the state of Jewish identity in the USSR. They thought they were operating secretly. In reality the KGB had been onto them from the beginning — and the KGB was not happy.

“It should also be noted that recently the staff of the Israeli embassy has increased its hostile activity. Traveling to the regions of the country with the greatest concentrations of Jews, they engage in conversations with Jews in synagogues and on the street and extol living conditions in Israel, incline Jews toward leaving the USSR and distribute Zionist and anti-Soviet literature,” read a top secret report to the Central Committee, the USSR’s top executive body, compiled by Pyotr Ivashutin, the deputy chairman of the KGB.

Ivashutin was alarmed by this covert activity and told the Committee that it needed a firm solution. His suggestion? Publish some articles in the press denouncing Zionism as a reactionary anti-Soviet ideology and then get some prominent Soviet rabbis to denounce this “false propaganda of the Zionists.”3

This weak Soviet response showed the country’s top leadership thought they could deal with the growth of Jewish nationalist ideas as if they were an outcrop of fake news — harmful weeds that could be pulled and replanted with something correct and beneficial. Using the parlance of today’s ideological info-warriors, they thought they could stop Zionism by fact-checking disinformation.

But Yakov’s extreme reaction to a single Nativ pamphlet hinted at a deeper problem. These Soviet bureaucrats were clearly underestimating their enemy. And their superficial solutions revealed a deep naivety about the intense power of these nationalist ideas — about how much they could attract and electrify.

Nativ’s propaganda methods might have been crude and simplistic. But that didn’t matter. They were having an outsized effect. Nativ’s nationalist mythology triggered something deep among a small but growing number of Jews in the Soviet Union. There was something that had been lacking in their lives and Nativ’s vision of the world filled that need. It wasn’t some materialist thing. It was spiritual, closer to a religious awakening. Whatever was happening to them wasn’t going to be stopped by a few condescending Pravda editorials and finger-wagging by a couple of state-approved rabbis.

Yakov, of course, didn’t know about any of this covert behind-the-scenes activity. Nor did he grasp the worry it induced in Soviet leadership. To him, the pamphlet found its way into his hands by accident. It was providence. He read a text. The vision came in a flash. He suddenly understood his true purpose and his true identity: It was all about blood and soil and historic belonging. He was a Jew. He was part of the Jewish Nation and he was meant to be there among his people in what he now believed was his homeland.

From then on he was changed man, consumed with a singular mission: to get out of Moscow and move to Israel. Nothing else mattered.

But as Yakov quickly found out, leaving the U.S.S.R. wasn’t going to be easy. This was 1956 and his country wasn’t in the business of letting anyone out.

To be continued.

Notes available to subscribers only…