My Ukrainian grandma and our lost history of pogroms

It seems unthinkable today — when people can’t shut up about their own little petty traumas — that a family would keep quiet about such a central, horrible experience. But those were different times.

This is an installment of The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Read the previous bit here.

I started working on the next chapter of my The Soviet Jew book right before Putin invaded Ukraine. With the shock of the war, it was hard to think or write about anything else. So I dropped it for a while. Now, more than four months into this disastrous thing, I’m slowly returning to what I started writing about back in February: the first few years of my grandmother Rosa’s life, who was born in a shtetl about a century ago in Ukraine but lived most of her life in Leningrad, where she worked as a midwife and nurse. And I’m glad I’m coming back to it. Because the historical and political moment into which she was born has some relevance to the war that’s now tearing Ukraine apart.

To a lot of people here in America the war in Ukraine might seem like it came out of nowhere. People throw words like “unprecedented” to describe it. But if you take a slightly longer view on the region, you’ll see that there’s little that’s truly new about it. The internal civil war, the nationalist vs. imperialist fights, the questions of Ukrainian identity and independence, the various territorial beefs, and the faraway outside imperial powers meddling in it all — while these elements aren’t in the same exact configuration as they were a hundred years ago in Ukraine when my grandmother was born, they’re close enough that the larger history around thems feels fresh and germane.

And there’s another thing. Looking at my family history in Ukraine and Russia — what I see is a people and a land that simply can’t catch a break. Every generation going back at least a century has seen a war or a revolution or a counter-revolution or a mix of all three. There have been multiple economic collapses, famines, and death on a scale that’s hard to imagine. People were constantly displaced and forced into shifts of cultural and personal identity. Living on the edge of this kind of rolling multigenerational turmoil and violence is totally normal for people from Russia and Ukraine and much of Soviet Union. It’s the just basic background and no one thinks it’s something that needs to be dwelt on too deeply. And as the war in Ukraine is now showing, this process is far from complete — if it ever will be.

I’d say most people in America can’t imagine living like this. And yet people here love to stir things up in Ukraine — all while smugly projecting their own simplistic notions of stability and morality.

But I’m a getting slightly ahead of myself… Let start with the basics.

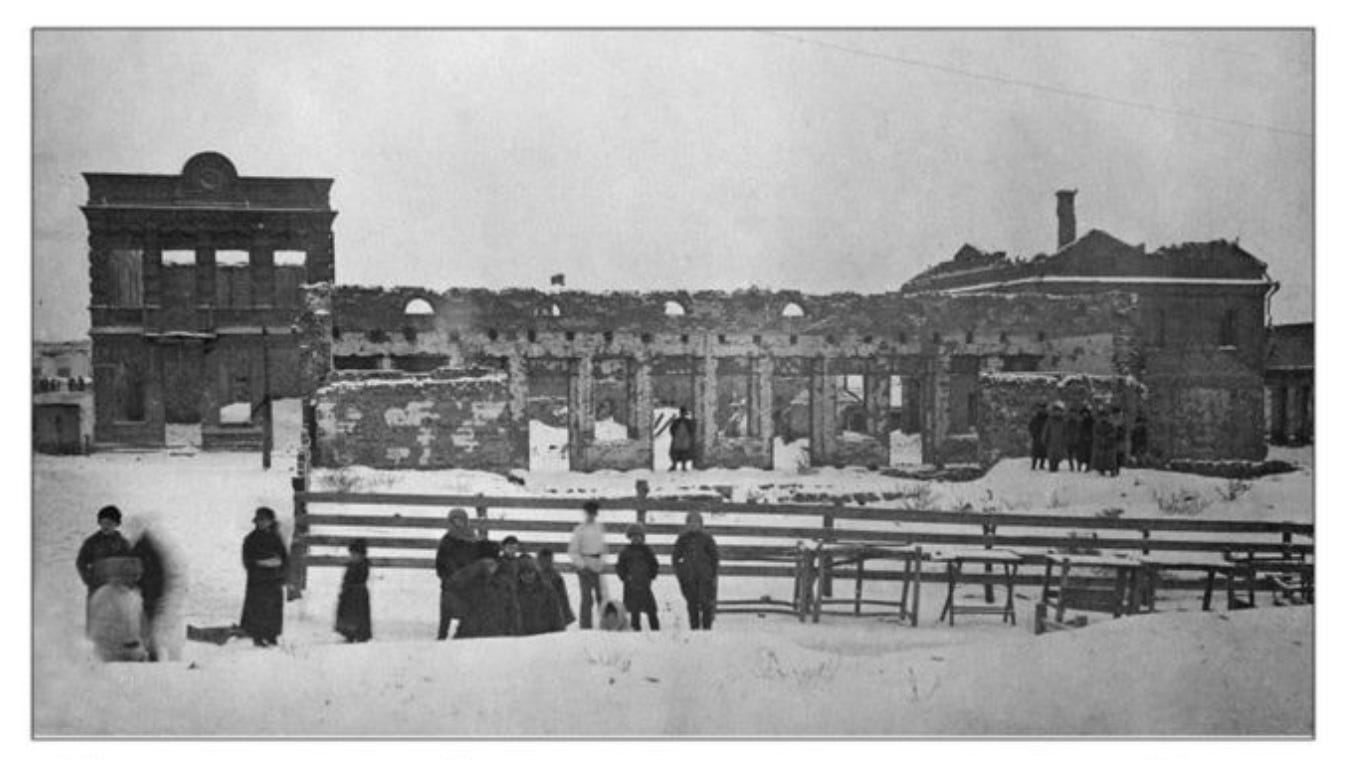

I couldn’t find a photo of my grandmother’s shtetl. It’s too insignificant. So here’s one of Korostyshev near Zhytomir.

Rosa is my grandmother on my mother’s side. She was born in 1919 in modern-day central Ukraine in Ryzhanovka, a shtetl about 120 miles south of Kiev. She had three older brothers and a twin sister — although the sister died of pneumonia or some other such sickness before she turned two.

In the late 19th century, Ryzhanovka’s big claim to fame was that an intricate Scythian burial site was found there. The grave, well preserved, dated back over 2,000 years and contained the remains of princess decked out in half a kilogram of gold ornaments. She’s now known as the “Scythian princess from Ryzhanovka” and you can see her remains today at the Archaeological Museum of Kraków.

These days, there doesn’t seem to be much that’s left in Ryzhanovka. There are some crumbling homes, an old kolhoz that might not exist anymore, grown-over plots of land, a small monument to the Red Army, and a privately installed memorial to Jews that were slaughtered here during World War II. I’ve never been to the place. But officially, about 900 people live there now — a fraction of the five or six thousand that lived there more than a century ago, about a third of them Jews.

But there used to be a lot of life in Ryzhanovka.

The Scythian princess from Ryzhanovka

Through most of the 19th century, it was a vibrant little shtetl. From the various bits and pieces of info I could pick up in the sparse reference books, it seems like more than half the people in Ryzhanovka were Ukrainian peasants. A third or so was Jewish — probably mostly merchants, craftsmen, and various peddlers. And there were also several Roman Catholic families — maybe ethnic Poles or Ukrainian elites who converted to Catholicism during Polish rule centuries earlier. The Catholics were almost certainly the big local landowners whose land the Ukrainian peasants worked. One of my relatives did make a trip out to Ryzhanovka from Leningrad in the 1950s or 60s. There were no Jews there anymore but according to him, back in the old times Jews had lived on one side of the village and the Ukrainian peasants on the other.

Just going by the basic numbers, Ryzhanovka looked like a typical smallish shtetl: It was a ”market town” — a place where people from the surrounding countryside came to buy and sell things, get their things fixed, stay at an inn, and get drunk at the local tavern. And, like in all shtetls, this trade was usually carried out by Jews. That had been true since the 16th century. After the creation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Polish Crown took control of most of Ukraine and began inviting Jews from Poland proper to run their new massive estates. In that sense Jews were agents of Polish colonization of Ukraine, helping Polish landlords develop and exploit these newly annexed territories.

Under this Polish feudal outsourcing regime, shtetls were originally private towns owned by Polish magnates. Jews lived there at the invitation of the absentee owners, running things and engaging in commerce — all while the lazy landowners collected their fees and their rents. In a lot of these places, Jews ran pretty much everything there was run: they managed forestry, managed farming and grain collection, organized town fairs, brewed alcohol, and ran the taverns. Over the years, more and more Jews came to live in these territories — bringing their extended families, setting up various shops and industries. I’m sure that’s how my family ended up there.

A lot of Jewish families became very rich and got very cosy with the Polish elites with this kind of arrangement — rich to the point that all they did was use their connections to get a monopoly contracts, which they would cut up and spread around among poorer subcontractor Jewish families: a forestry contract here, a contract to run the local market there, and a booze brewing monopoly over here. The smaller Jewish subcontractors actually did the work, while the big Jewish contractors sat back and pocketed the subcontracting fees. So there multiple levels of parasitism — one for the Polish landlords, the other for the big Jewish contractors. Towards the bottom of the pyramid were the poorer Jews who did the work, while at the very bottom were Ukrainian peasants who technically worked their landlord’s land, but dealt almost exclusively with the landlord’s local Jewish agent.

This subcontracting industry was very advanced. It kind of reminds me of how big military companies like Lockheed Martin operate today. They lobby and throw political money around to get those fat military contracts, which they turn around and farm out to smaller military subcontractors, all while demanding kickbacks and bribes. Nothing new under the sun!

Things mostly continued in a similar kind of set up when the Russian Crown took control of Central Ukraine towards the end of 18th century — although the whole system started to go through a period of decline and population loss as the 19th century progressed.

So right before my grandmother was born in Ryzhanovka it was probably much poorer and shabbier than it had been even a century century earlier. Still, it was a shtetl and adhered to the same kind of pattern. The Jews ran the business side of things. The Ukrainian peasants worked landlord’s fields. Ryzhanovka had a market and a bunch of businesses owned by the local Jews: a sawmill, an alcohol distillery, a few bakeries.

My great-grandmother and great-grandfather out picnicking in the field.

Looking at this history, it’s pretty clear that my ancestors had lived in the area for many centuries. But like all simple Jews, my family knows almost nothing about what these old timers were up to. They left no trace. No paperwork, not much of a written record. About the only thing my mother knows is that my great-grandparents were small time merchants. They had a shop or a stall — probably in the town’s market — selling flour, bread, grains, and maybe horse feed. A business directory compiled a few years before Czarist Russia collapsed lists them as engaging in the “flour” business.

As to how they lived? All that my mom knows is that the family had a small house and owned a cow, which was apparently no small thing in those days. They also had enough dough to buy special clothes that they wore on shabbat. “They were very proud that the men in the family could afford to buy silk shirts,” my mother recalls her mother telling her. My grandmother was just a child back then but she remembered the silk shirts because they were very hard to iron.

As for language, they all spoke Yiddish, barely knew any Russian, and must have known enough Ukrainian to talk to their neighbors. My mother says that my great-grandmother couldn’t read Russian. Even for my grandmother, Russian was basically a foreign language — which she had to learn formally after moved to Leningrad in the late 1930s.

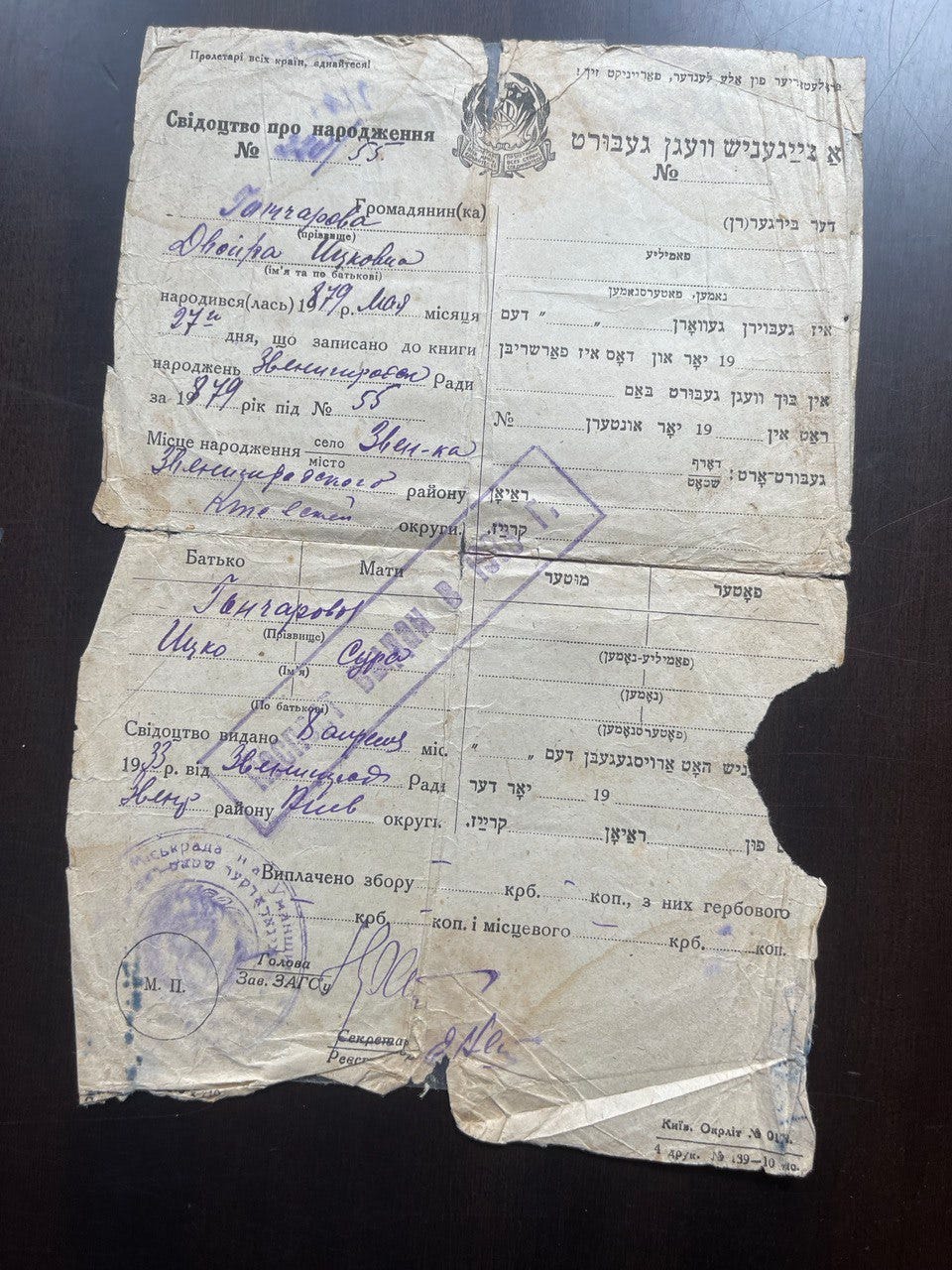

Russian simply was not used in the shtetl. Even in the 1930s, official Soviet documents in their Ukrainian region were handled in two languages: Ukrainian and Yiddish.

Ukrainian on the left, Yiddish on the right. A document given out by Soviet Ukraine in 1933. Even the official stamp had Yiddish in it.

I guess by today’s standards my family would be considered ”Ukrainian.” But I wonder if they thought of themselves that way. Probably not, not in terms of that kind of specific nationality. They probably just thought of themselves as Jews. They all spoke Yiddish and practiced Judaism but lived alongside Christians who spoke other languages — Ukrainian, Russian, maybe even a bit of Polish.

When the 20th century rolled around, the old world of the shtetl had been in decline for decades. But after World War I, the shtetl went through a whole other level of collapse.

A year before my grandmother was conceived, Ryzhanovka — like a lot of other shtetls — found itself at the center of a bloody multidimensional conflict. World War I expanded the Civil War and chaos that brought into a ridiculously confusing number of players. There was the Red Army, the Whites, Petliura’s nationalist forces, Ukrainian anarchists, the Germans, roving bands of pissed off peasants. In the span of three years, the shtetl was occupied and changed hands multiple times — and every time it was “liberated,” the Jews there got pogromed. The thing is, pretty much everyone on the list had it in for the Jews in one way or another.

The Germans took control of Ryzhanovka in 1918. There was a pogrom after that. A warlord allied with Petliura’s nationalist forces — a guy named Tsvetkovsky — took control of the shtetl in 1919. His people did a pogrom there, too. Then the White Russian Volunteer Army kicked out the nationalists and occupied the village. They, too, did a pogrom.

Soviet poster showing the different forces at work in the region after the Treaty Brest-Litovsk.

All in all, according to the Encyclopedia of Russian Jewry, something like 30 people were killed in Ryzhanovka because of all these pogroms. I don’t know what sources the encyclopedia used for the statistics. Ryzhanovka was a small shtetl and is essentially forgotten now, so it’s been hard to get any detailed info on it without access to archives and oral histories that might or might not exist in various institutions. But after combing through a bunch of literature on the topic of pogroms in Ukraine, I did find a reference that implied the destruction there was much worse that the sparse encyclopedia entry let on.

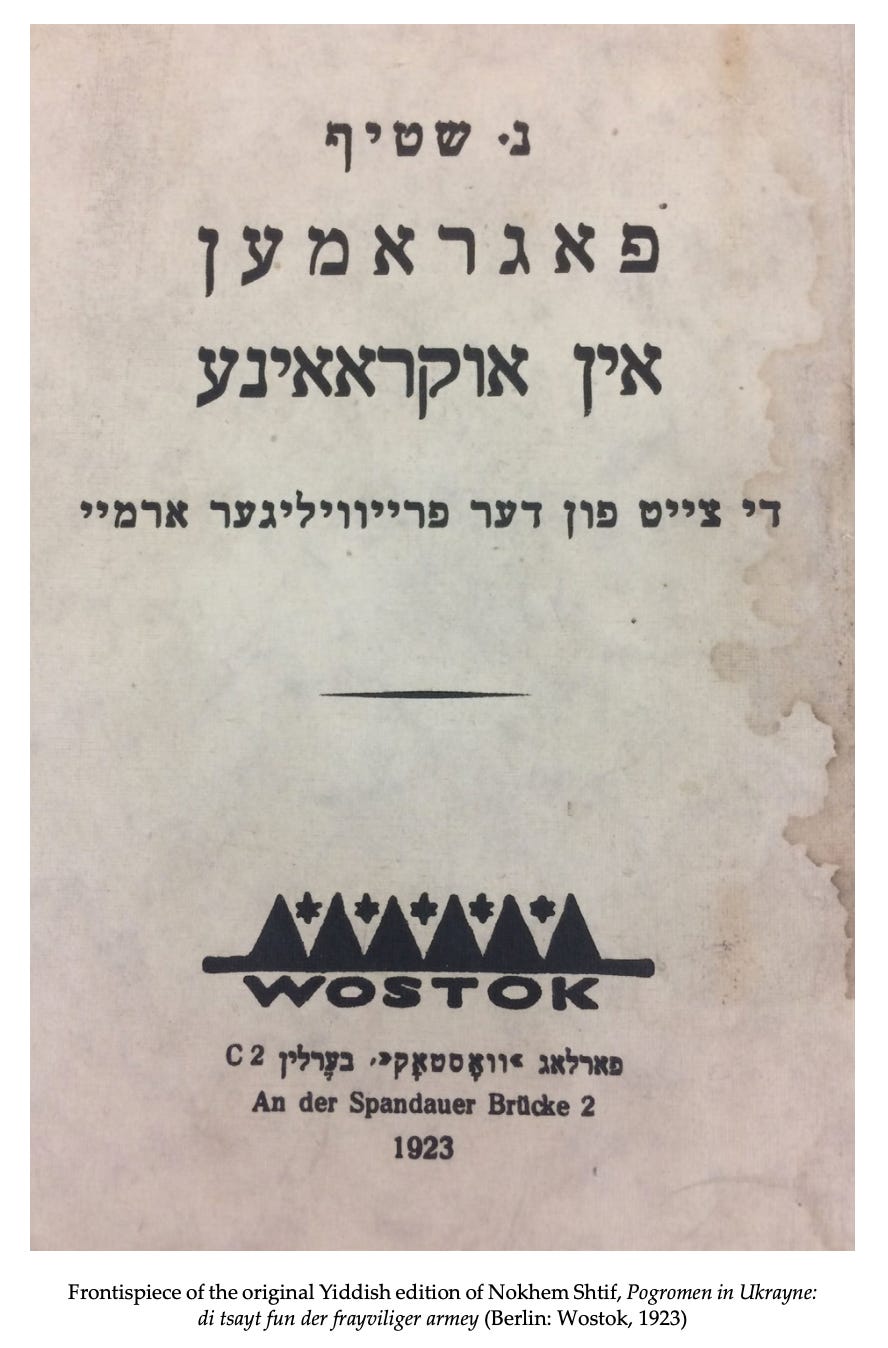

I found the reference in The Pogroms in Ukraine, 1918–19 — a book by published in Berlin 1923 by Nokhem Shtif, a Jewish political activist, linguist, and historian. He wrote it in the immediate aftermath of the pogroms that swept through Ukraine during the Civil War. Now almost entirely forgotten, these pogroms left a huge trail of Jewish bodies: anywhere from 50,000 to 200,000 Jews were brutally murdered. Countless others were raped and maimed and robbed and displaced.

While there was a big focus at the time on the role that Symon Petliura’s Ukrainian Army played in these massacres — a role that got international attention after Petliura was assassinated in Paris by a Ukrainian Jew who lost his entire family in the pogroms — Nokhem Shtif focused his study on the pogroms carried out by the White Russian Volunteer Army, which was headed Anton Denikin at the time.

Shtif’s based his book on survivor testimonies that he and others collected right after the pogroms. And as the evidence he collected showed, “Denikin’s Pogroms” were possibly the most brutal of them all — more organized and thorough and more focused on rape and looting than ones carried out by Petliura’s forces and other unaffiliated local gangs and warlords.

Aside from using loot taken from Jews as a way of paying his soldiers, there was an ideological component to the slaughter: Jews, according to propaganda pumped up by Denikin’s Volunteer Army, were synonymous with Bolshevism, and that made then main enemy of the Great Russia they were trying to restore and take back from a a Jew-dominated Bolshevist conspiracy. So shtetl Jews had to pay the price, even if most of them were as opposed to Bolshevism as the Whites and welcomed the Volunteer Army to their shtetl as liberators, which was often the case. But conflating Bolshevism with Jews and treating them as an enemy wasn’t restricted to the White Russians — pretty much everyone thought so at the time, including Petliura’s forces.

I want to get into Denikin’s (and Petliura’s) pogroms in a greater detail in my later newsletter. What’s important to remember is that his Volunteer Army was being backed at the time by the Allies: America, France, Britain. So they were a foreign-backed force. But these days Denikin and the White Army are seen as anti-western heroes in Russia. Even Putin is a fan of Denikin’s “Great Undivided Russia” politics.

The reason I mention Shtif’s study here is because there is a short appendix in his book that lists all the shtetls that were destroyed by Denikin’s forces. And there, among them, is my grandmother’s shtetl — Ryzhanovka.

What that means is not exactly clear, other than the fact that destruction of the Jewish community there must have been pretty serious. And Shtif’s little entry does seem to be confirmed by the population statistics I found in the Encyclopedia of Russian Jewry. Ryzhanovka’s post-Civil War Jewish population dropped by something like 80 percent — from 2,500 to 500.

“For United Russia” — a White Russian Volunteer Army propaganda poster calling on Russians to fight Bolshevism. The Bolsheviks are pictured as a demonic red dragon that strangling the “heart of Russia.”

What did all these various pogroms look like? I couldn’t find any accounts for Ryzhanovka but there are several recorded accounts of the violence by people who lived nearby — including one from Boyarka, a mestechko/shetel of about 200 Jewish families in what what was then Zvenigorod, the same county that my grandmother’s shtetl was in. It’s recounted by someone named Nekhamov, who from his story, had a relative killed in the pogroms.

A couple of notes before I quote his testimony.

Nekhamov doesn’t mention Denikin’s Volunteer Army maybe because Denikin’s Cossacks never entered his shtetl. He does mention the same Petliura-allied warlord who had also pogromed Ryzhanovka — a guy named Tsvetkovsky. As far as I can tell, the “Kazakov-Popov gang” he talks about is also a minor band allied with Petliura’s forces.

Also notice that Nekhamov keeps saying these bands dressed up as Bolsheviks and forced Jews to sing Bolshevik songs while leading them to slaughter. Apparently this was a normal thing for anti-Bolshevik forces to do back then: to dress up as communists while carrying their pogroms. I’ve seen similar stories in other survivor testimonies. In a few of them, bands pretended to be Bolsheviks and carried red flags when they entered the shtetls in order to draw out any Jews who might be sympathetic the communist cause…and then they preceded to slaughter anyone who came out to greet them.

Anyway, here’s how Nekhamov described what happened to his shtetl during the Civil War:

On June 1918, an armed insurgent gang committed violence against the peaceful Jewish population. They robbed, killed, and wounded — Prokhor Nekhama fell victim. This gang continued to dominate the whole winter. It is obvious what the defenseless Jewish population of our town, where there are only up to 200 families, was forced to go through. Local hooligans operated all night long. They beat and killed Sokol Sonya and Rzhavskaya Gdal. Thus the whole of 1918 continued.

We had not yet had time to rest a little from the experiences, when 1919 came, especially the black day of mourning on June 15, when the Kazakov-Popov gang disguised in revolutionary clothes and red signs appeared from somewhere, and began to order all Jewish men into the synagogue. They demanded an unbearable [monetary] contribution, which was done. But people are insatiable animals. They stripped us naked and drove us somewhere in the direction of the village.

Semyonovka, where the river flows, so deep and fast, in order to inflict an inhuman judgment on us. On the way they were forced to sing various Bolshevik songs, forced to trot, and when some old people were not able to do this, they cut them to pieces. Thus, they ran a distance of 4 versts to the famous river, which in its depths buried more than a hundred lives. Reaching the river, we were placed in a line of 4 people and ordered to jump into the river. Those who refused to comply, they shot at them. So that was no other way but to jump. It was thought that some who could swim managed to escape and returned home naked. The following persons were shot: Vashpolsky Judas, Sinitsky Avrum, Sokol Ilya, his son Danil Povkalinsky, Loser Dubov, Aron Krupnik, Yankel Shubinsky, Simka Prokhorovsky, Gershko Postovetsky, Volko Grinfeld, Tsipa Rakhlis, Shlema Divinsky. The number of wounded up to 40 people.

The robbery took on a serious character. There was no house that was not subject to robbery. The inhabitants were afraid to spend the night at home and fled across the steppes and meadows, and when some families dared to spend the night at home, they were cut. After the offensive, a self-defense unit was organized. Thanks to this, some time passed safely.

But at the beginning of 1920, the self-defense was disarmed by local rebels, since they accused us of being communists. Thus, the rebels held out for three months.

And in September 1920, the gangs of Tsvetkovsky, Gryzl and Budyonnovists suddenly perpetrated a pogrom under the flag of the Bolsheviks. There was a general massacre. Babies were slaughtered in front of their mothers, unbearable violence was committed against the inhabitants, and the number of new victims that day was 83 people, and the rest were wounded, beaten and raped.

So my grandmother Rosa was conceived right in the middle of all this — and then spent the first year of her life in a shtetl beset by murder and rape.

It’s hard to imagine what her mother — first pregnant and then having to care for a child — had to go through. It’s pretty clear that it must have been a shocking and defining event for her and her family. Yet no one from that generation talked about it — not my grandmother, not my great-grandmother. Until I started digging into the history of Ryzhanovka, my mom had no idea that her mother and grandmother and various grand-uncles almost certainly lived through this horror.

It seems unthinkable today in America — where people can’t shut up about their own little petty traumas — that a family would keep quiet about such a central horrible experience. But those were different times. People kept the horrors that they went through hidden — hidden even from their children. I guess it’s not that surprising. These pogroms were just the start of several decades of bloody trauma and death.

Right after going through the Civil War, they had to deal with a famine, then some more starvation during the Siege of Leningrad, then a genocidal war by Germany against the Soviet Union — a war that wiped out entire branches of my extended family, including my grandmother’s first husband. In a short period of time, they accumulated enough trauma to last many lifetimes. So much trauma that “trauma” lost any meaning. And anyway, what’s the point of picking at the scabs and reliving the horrors of the past? How could that possibly help?

So no one talked about it. But because no one talked about it, we don’t know what my my family actually went through during the pogroms. Was my great-grandmother able to successfully flee and hide? Did they get swept up in the violence? Was anyone beaten? Raped? Injured? Robbed? We just don’t know. That family history has been lost forever.

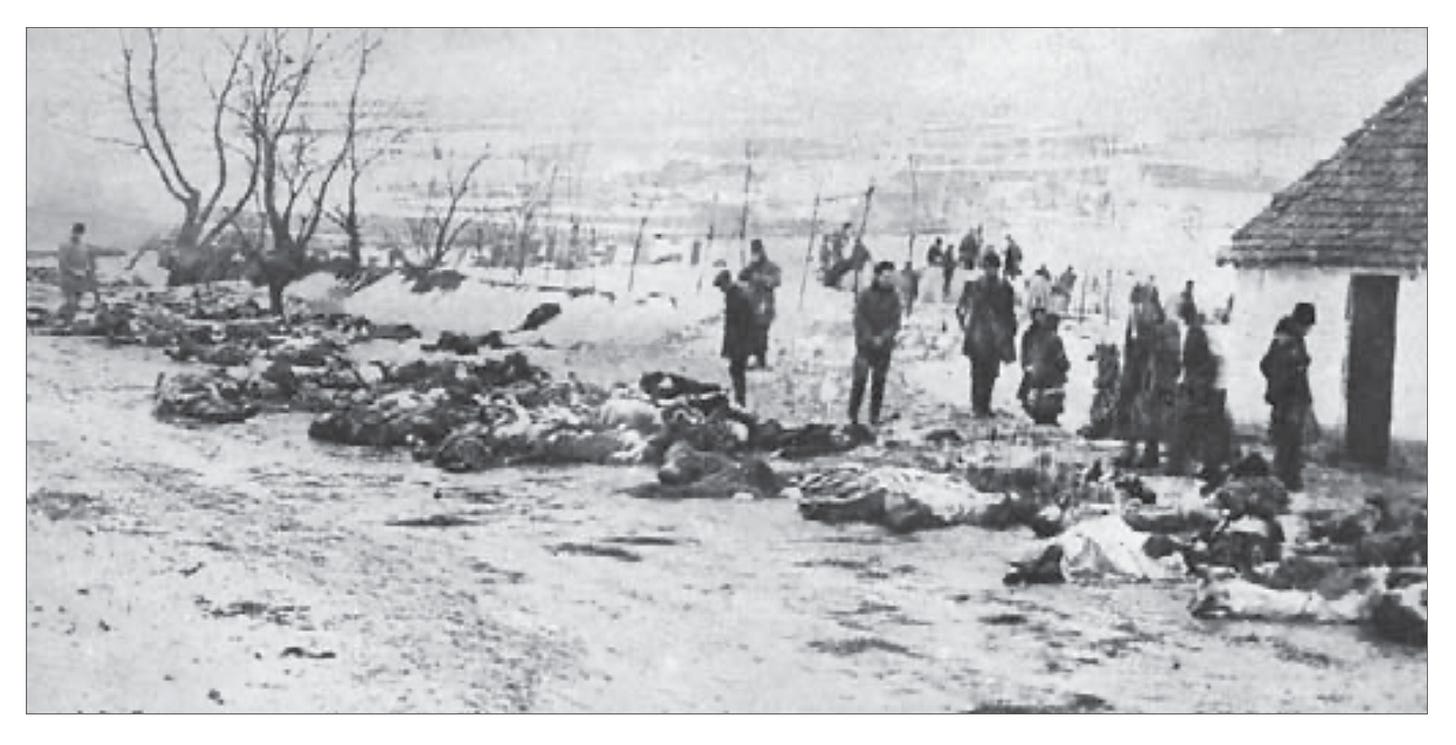

Aftermath of a two separate pogroms. Somewhere in Ukraine.

The pogroms was more destructive to Ryzhanovka than I originally thought when I first started looking into this history. Still, the shtetl wasn’t totally destroyed. My family kept living there when the Bolsheviks began consolidating control of Ukraine after 1920. And they stayed living there right up until 1933.

But then that year my grandmother and her family suddenly left the shtetl and headed for Crimea. Why? What forced them to leave the shtetl at that point — when they had held on through all the pogroms and mass murder? Well, that’s another family mystery.

My guess is that collectivization played a part. But the main thing I think they were fleeing was the famine that swept through Ukraine and Southern Russia and other Soviet Republics.

To be continued…

—Yasha Levine

Read the rest of this serialized book: The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale.

Thank you for the history of your family and Ukraine. Americans basically are clueless when it comes to history even in the next town.

Watching our political situation I am afraid we may be heading to a future that will duplicate this horrible history.

I have been following your blog for a while now. I am so grateful for your researching and your writing. My family has also never spoken about our history so I have only tiny amounts of history. Thank you so much for writing what you are learning about our shared history. My grandmother was born in 1918 in Uman, Ukraine. They left in 1920 after surviving a pogrom by hiding in a basement. They then walked across the mountains into Romania. I feel a sense of belonging as you spell out the history of our ancestors. Something deep is filling into my being. A deep thank you for your work. 🙏