This is is another installment of The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Read the previous installment.

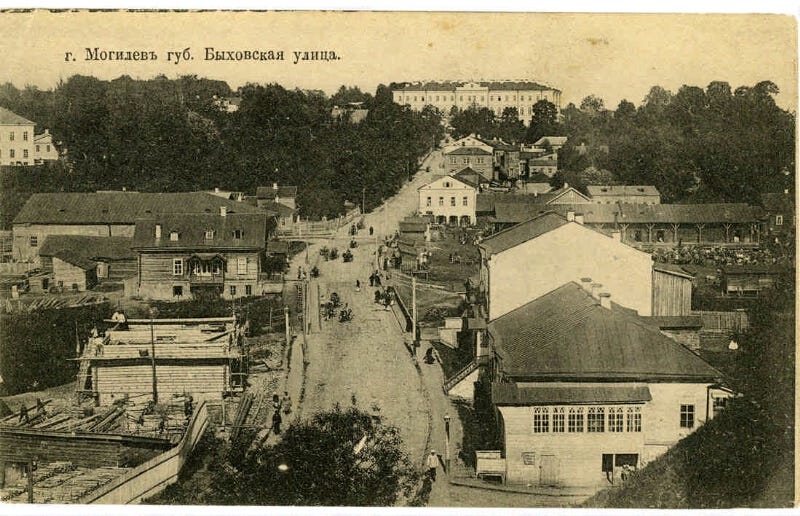

Mogilev, 1915.

To pick up from where I left off last week…So Hertz Nahum-Medelovich is my grandfather on my mother’s side. He was born in Mogilev in 1912, the ninth and youngest child. At the time, his whole family — his father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, and all his siblings — lived in a small house near the banks of the Dnepr River, where his father had his shop fixing horse carriages. The house was probably in a Jewish neighborhood and was surrounded by other petit bourgeois small time business Jews engaged in their various trades in this provincial city on the western periphery of the Russian Empire.

Two years after he was born, Russia entered World War I. Five years after he was born, the Russian Revolution happened and sometime later his whole family moved to a room in an apartment in the center of the city. I’m guessing the new bosses did not like petit bourgeois types like my grandfather running their individualistic businesses out of their own shops, so they were all moved into cramped apartment rooms seized from the upper classes like the good proletariats they were.

Back when Hertz was born Mogilev was a very Jewish city, had been for centuries — ever since Jews took up shop there in the late Middle Age. But right around the time my grandfather was born, that old Jewish world had started to change. All over the Pale of Settlement where most of the Jew lived, a multidimensional internal war that pitted various ideologies and strains of Judaism: Orthodoxism vs Hasidism vs Secularism and Zionism vs Bundism vs various strains of Russian Marxism. It was a multifront war and everyone hated everyone else. For instance, I read that Chabad wanted to form a united front of religious Jews and rejected an alliance with the godless Zionists, while the Bundists and Marxists hated all of them — the Torah huggers and the Zionists. In the end, though, the religious Jews and the Zionists lost big. Well, almost everyone other than the Bolsheviks lost big. And then most of the early Bolsheviks also lost…their lives.

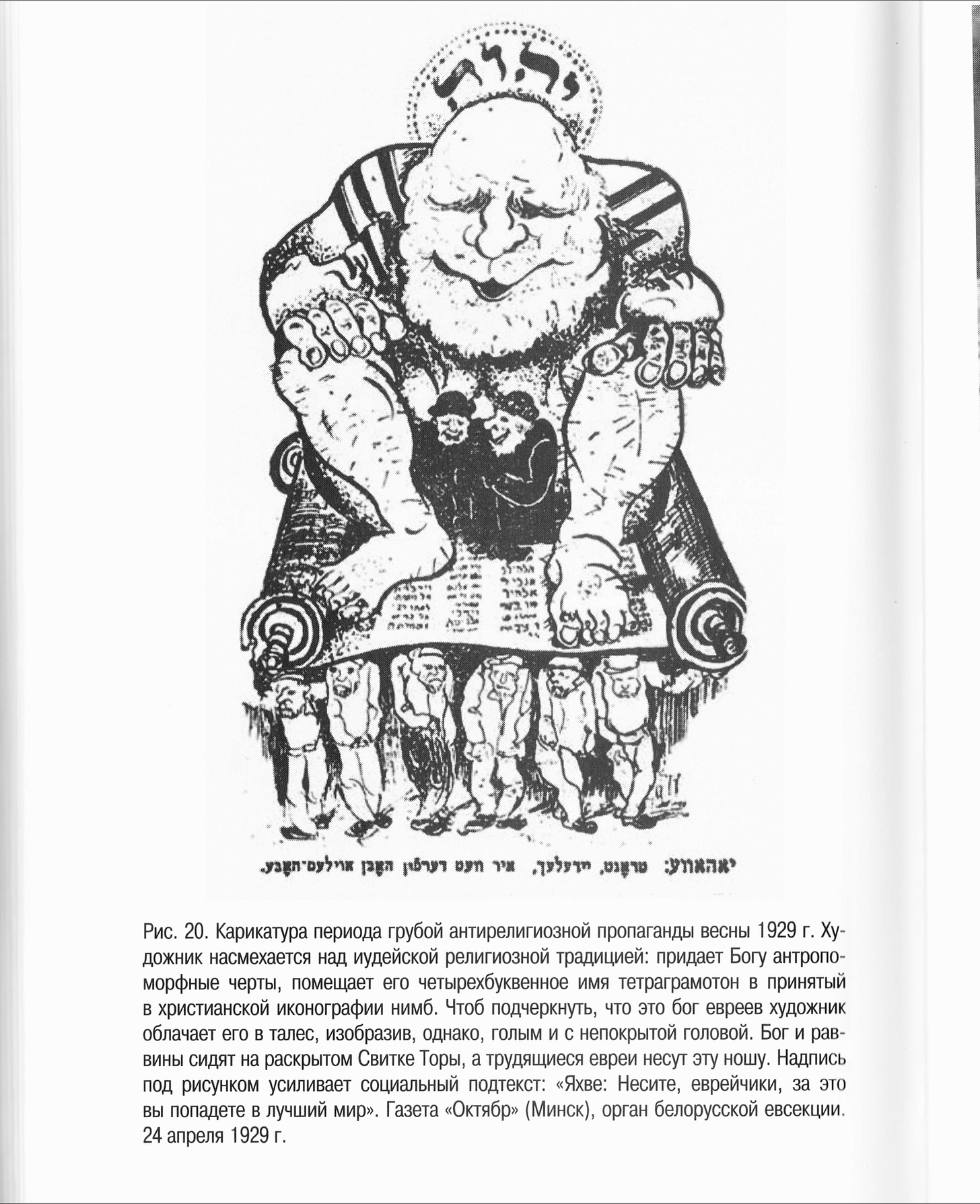

Anyway, few in today’s Soviet Jewish diaspora know or care to remember, but back when the revolution was at its most exciting and promising, young Jews — grandparents and great-grandparents to Soviet immigrants alive today — were some of the biggest haters of the Jews around and today would certainly be tagged as huge antisemites. They waged a war against religion and tradition. They printed reams of “anti-Jewish” propaganda, staged “anti-Jewish” plays, disrupted religious holidays, held show trials, and ultimately closed Jewish religious schools and synagogues, turning them into worker cultural centers. So the biggest enemy of Jewish tradition weren’t non-Jews — and it sure wan’t Stalin, at least not then. It was other Jews who wanted to dismantle that old conservative world.

An anti-religious cartoon in a paper put out by the Belarussian Jewish Section, 1929. (Source)

My grandparents on my father’s side were involved in this Bolshevik Jewish cultural revolution against Jewish tradition in Ukraine — in fact, I believe that’s how they met. But not Hertz, my mom’s father. No doubt Hertz witnessed some of this anti-Judaism agitation as a kid in Mogilev — how could he not? But he was never political as far as my mother knows. He was passively Soviet secular, like most people of his generation. He became a member of the Communist Party during the Great Fatherland War but, again, only passively. His name was automatically entered into the rolls. Everyone was expected to join.

I recently found out that Hertz’s father — my great-grandfather — was very religious and kept sneaking away to secretly pray even after that kind of thing was frowned up in the Soviet Union. And his kids didn’t turn him in. So…

Anyway, Hertz came of age in the 1930s — in the age of rapid industrialization, when many of these intra-communal Jewish fights had already gotten officially settled. In that way my grandfather was a typical Soviet young man of his generation. Like millions of others like him, he left his provincial home town and headed out to a rapidly industrializing city — in his case, Leningrad.

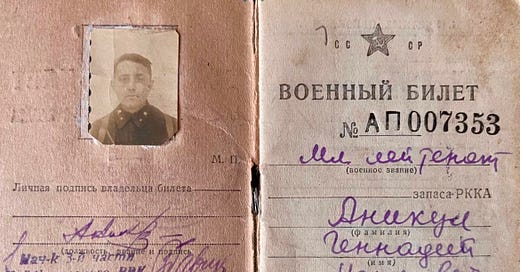

Hertz looking handsome in uniform.

His mom died in 1927, when he was 15. When he was 17 or 18, he left Mogilev and moved in with his older bother Arkady. They lived in a single room in the center of Leningrad that had been given to Arkady by the factory where he worked. Hertz eventually got a job in that same factory working as a welder. What factory did he work in? Details are hazy but mostly likely it was Skorohod, a shoe factory.

With about 2.5 million people at the time, Leningrad was the second largest city in the Soviet Union. Mogilev was a village compared to it. Like most young Jews, at some point after coming to Leningrad, he Russified his first name and patronymic — changing it from a very shtetl-sounding Hertz Nahem-Medelavich to Gennady Naumovich. It’s not surprising. A lot of Jews Russified their names to better fit into the big Russian cultural world of the Soviet Union.

In Leningrad, Gennady lived in a worker dormitory and enjoyed the newfound freedom of living in a big bustling city — going to shows, hanging out with his buddies, and dating girls. “He was handsome, had blue eyes,” my mom told me. He was popular with the ladies. His brother wanted him to court and possibly marry his girlfriend’s sister, but fate wouldn’t have it.

In 1933, Gennady was drafted into the Red Army and served out his term somewhere near Baku. My mom said that loved swimming in the Caspian Sea and would tell her stories about the the snakes swarmed in the water there.

He finished his mandatory army service in 1938 and went back to work as a welder in Leningrad. But, again, his civilian life wasn’t destined to last. About a year later, in September 1939, he got called up and sent to Poland as part of the Soviet Union’s partition and occupation. He didn’t see much action in Poland, as the Red Army faced almost no resistance. And in early 1940, he got shifted to the front in the war with Finland — the Winter War — where he served on skis in the dense frozen forests near Lake Ladoga. “They weren’t prepared for the Finnish winter. It was incredibly cold. They didn’t have any proper equipment. They had almost no skies. Soldiers had to improvise, had to make their own skies — out of pieces of wood. They had no valenki so a lot of soldiers got frostbite. They had no white camoflague suits and no proper rifles. They were being picked off by Finnish snipers like they were rabbits,” my mom recalled, based on what my grandfather told her about the war when she was a child.