Fixing the czar’s carriage

I always thought that I had descended from a shtetl shoemaker. What could be more stereotypical, right? Turns out I had been misled.

This is is another installment of The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Read the previous installment here.

As I wrote you last week, I’m finally rebooting this book after months of inactivity. Now that we’re a bit settled again and Eurasia has her grandmother around to help us out, I can finally lash myself to this networked word processing apparatus and get to work.

I’m sitting at my desk at our new place in San Francisco as I write this, a block away from Haight Street. It’s kinda sunny. A bunch of big rain storms just passed over the Bay Area. Shoppers are out in force, scurrying by below my window, circling the block in their cars looking for parking. The woman who usually sleeps on the street just across from us has been gone for days now. I wonder where she is — hopefully at a shelter where she can get out of the cold and the rain. It’s strange living in this neighborhood. When I was an immigrant teen in San Francisco, I used to come out here with my friends to score drugs and buy tickets to crappy underground raves. Now I’m a father and an upstanding citizen, pushing a stroller around. No more raves for me. Still doing drugs, though — just better ones.

So how I do restart this thing and get the juices flowing? It’s been so long since my last real update, I think a quick reintroduction is probably in order.

Immigrant narratives in America tend to skew one way: they’re produced by weaponized immigrants for an audience and a culture that prizes and cultivates weaponized immigrants. The job of immigrant stories is to reflect America’s own narratives about itself — to confirm America’s superiority and to reaffirm all the negative stereotypes Americans have about their society.

As I wrote in the introduction to this thing last summer, I want to write up a different immigrant story — one that has a bit more nuance to it.

The cliche that everyone expects out of people like me is a story about a bright boy being saved from a grim fate under Soviet authoritarianism, now living out his life in a dynamic and prosperous and free society. But that’s not really how I see it. The reality is that my family fled one failed society only to end up in a society that is itself entering an accelerated phase of stagnation and failure. But unlike our first escape, there’s really nowhere to run for us this time. The American Way has conquered the planet and it’s taking everyone down with it.

So where to start? I guess at the very beginning — with my family history in the Russian Empire and Soviet Union.

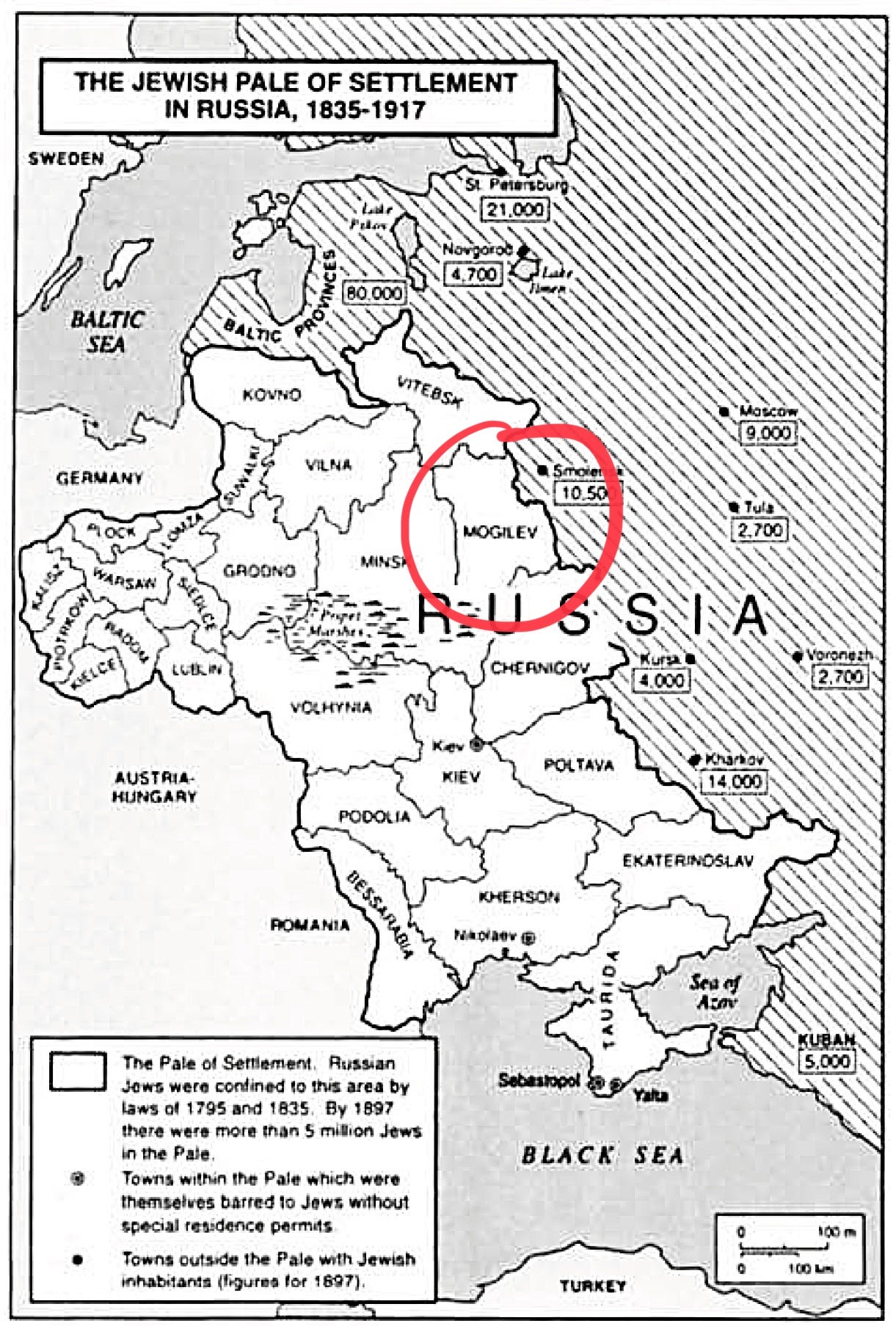

My knowledge of my ancestors — even close ones like my grandparents — is very spotty. From the larger academic history, I know that my people have been bouncing around lands that’ve been known variously as the Kievian Rus, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Russian Empire. We’ve been here hundreds of years and maybe longer, depending on your view on how the majority of us shifty Jews ended up in that land. Did we migrate over there with our donkeys and goats and camels and Torah scrolls and multiple wives all the way from the Holy Land, as the standard Israeli history would have it? Was it just few a Jewish traders who came with their goods from the Middle East to Europe and then took shiksa for wives and forced them to convert? Did some of come us come from the east through the Caucuses and Crimea and then eventually merged with our more dominant Yiddish-speaking Jewish communities from the west — converging on modern day Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland in a sort of pincer migration maneuver? A lot of this stuff is very speculative. And usually a Jew’s view on the origins issue depends on what side of the “Are we indigenous to Judea?” debate they come down on.

But wherever we came from and whoever we fucked and merged with, it’s pretty clear that we Jews have been around Eastern and Central Eurasia for a long, long time — enough be basically indigenous to the region. But while we’ve been there a long time, my own family’s collective memory only goes back only a few generations. I guess that’s normal. We come from a very simple background and simple people don’t transmit too much information to the future about their past — no letters, no diaries, no ownership records, and too much displacement, too much movement. So all I’ve got are a few facts and a few family stories.

Still it’s worth to get some of it down on paper and to try to reconstruct a basic timeline to get a sense of my family got from there to here.

So to begin…I’ll start with the Belarusian side of my family: my maternal grandfather Gennady Naumovich, who left Mogilev for the bright industrializing lights of Leningrad in the 1930s.

Gennady looking handsome in uniform.

I don’t remember my grandfather Gennady very well. He died when I was just six, when my family lived together in a small two bedroom apartment on the southwestern outskirts of Leningrad. I do seem remember the big scar and indentation on his forehead. He’d have to wear a hat even if it was slightly cold. A chunk of his skull was missing, so he’d freeze his brain and get headaches. But my memories of him are just flashes and I can’t be sure if they’re real memories or those that came about because of stories my mother told me or pictures that I saw and which then recombined with my own experiences and slowly got established in my mind as “true memories.”

I think the strongest real memory I have of my grandfather is not really a memory of him at all — but a memory about him. I remember I was in the living room of our Leningrad apartment. We had a typical Soviet bookcase with some books and nice dinnerware on shelves behind glass. My mom was with me in there, sitting on the couch. I think maybe a guest was there, too. I took a book off a shelf and, looking through it, found a picture of my grandfather between some of the pages. I started crying when I saw the photo. Did I cry because I actually missed my grandfather or because it was a performative thing — something I knew I ought to do because that’s what my mom would do? I dunno.

Weird how some memories burn into your mind, while others fall away.

As far back as I can remember, my mom’s family lore had it that my grandfather’s father — Nahem-Medel — was a poor cobbler. He moved to Mogilev from a nearby shtetl called Lukoml. He married a woman named Rivka, had a family, and plied his trade making shoes. His marriage record didn’t record his profession, but simply categorized him as “petite bourgeoisie.”

Nahem-Medel and Rivka had a big a family. Altogether, my great-grandparents had eleven kids and at least three generations lived together under one roof. Not all of the kids survived past childhood, and that included a pair young twin girls who got burned in some freakish accident at the kitchen stove and died from their wounds. So there were a lot mouths to feed and a lot of feet to shod. My mom would retell the old family joke that Nahem-Medel had so many children that by the time he’d finish making shoes for all of them, he’d have to start all over again.

So I always thought that I had descended from a shtetl shoemaker. What could be more stereotypical, right? Well, it turns out I had been misled.

A few months ago, my mom called her cousin in Israel to confirm a few details about my grandfather’s military service during the Great Fatherland War. Instead, she got something unexpected. She found out that my great-grandfather Nahem-Medel didn’t make shoes for a living. He was a mechanic. He fixed horse buggies and carriages, and the family all lived together in the same tiny house near the Dnieper River where he had his workshop.

Apparently he was well-known in Mogilev for the quality of his work — so much so that Nicholas II, Czar of Russia in its Entirety, got his carriage fixed at his shop when it broke down in town. Supposedly, the czar snapped his axle. Maybe he was taking the turns to fast?

But I was surprised. My grandfather fixed the czar’s carriage? That’s a serious claim to fame! I had no idea my family got so close to a historical figure like that. But maybe it was a self-aggrandizing family myth? A cool story that got passed down? I mean, back then Mogilev a smallish provincial town with a population of about 50,000. More than half of the people there were Jewish. So what the hell was the czar doing cruising around there? Shouldn’t he have been zipping by as fast as possible on his upholstered imperial train to a more ritzy destination?

But no, apparently it’s true. Nahem-Medel told his daughter and his daughter told her daughter, my mom’s cousin. “Why would my mother make up such a crazy story?” the cousin asked my mom. And the timeline does checkout, historically.

Russia entered World War I in 1914, two years after my grandfather was born. In 1915, Russia’s moved its central military command — the Stavka — to Mogilev. So for a short time that made this provincial city the center of the Russian world. It was where Nicholas II, his generals, a big chunk of his court, and a bunch of foreign ambassadors and their retinues spent their time. So it makes sense that Nicholas would be in zipping around Mogilev on his royal buggy.

Nicholas II and his tsarevich inspecting the troops, apparently somewhere in Mogilev.

I wonder if fixing the czar’s carriage turned out to be good for generating business? If nothing else it was a great advertising opportunity for Nahem’s shop:

“Czar quality at shtetl prices!”

“Come in as Yankel, leave a Czar!”

Unfortunately, my great-grandfather wouldn’t have been able to bank on the czar association for long — not with the revolution and all that happening just a few years later.

To be continued…

—Yasha Levine

This is part of my serialized book, The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale.