Lev Trotsky and the forgotten Jews

His childhood gives a sense of a different kind of Jewish life that existed in the Russian Empire just before it blown to bits by rot and wars and revolutions.

This part two of Chapter Two of The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Read part one here.

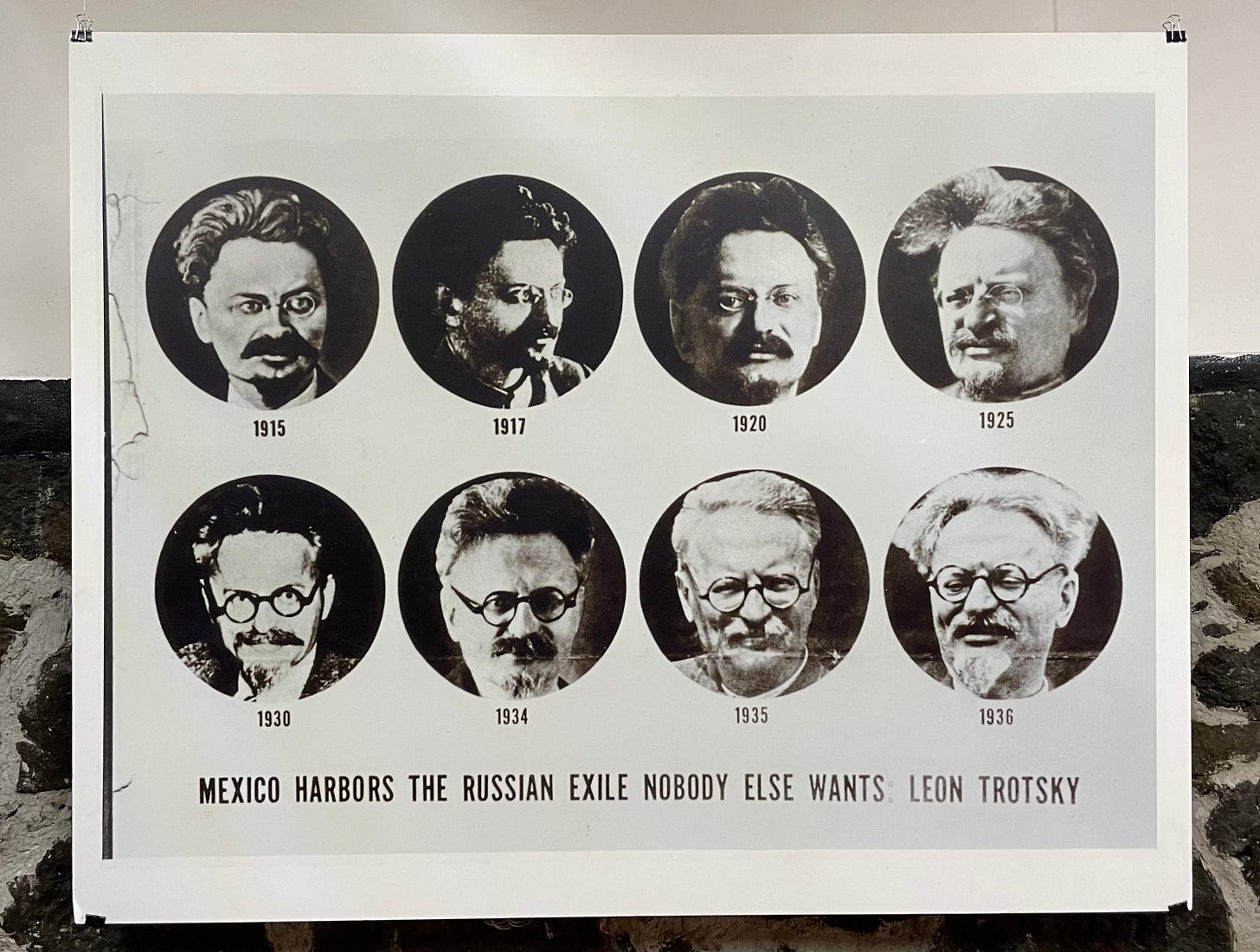

A few days ago we visited the Museo Casa de León Trotsky — the house in Mexico City where Trotsky lived out his last years and where he was assassinated by Ramón Mercader, who was a Spanish communist and an NKVD agent.

We were expecting a modest apartment but instead we found ourselves in a small villa surrounded by a giant wall with guard towers. When Trotsky lived here in the late 1930s, it must have been a much less developed, more rural area. He had a big yard where he raised chickens and rabbits, which he would eat. Now there’s a loud freeway running right up against the property and high rises towering over it.

The place has a good feel to it. It’s not big for a big time political leader like Trotsky, but not small either. It has a study, an office for his secretary, two bedrooms, a big bathroom, a dining room, a separate house for his guards and security detail. Probably the most surprising thing about the place were the guard towers with slits for shooting in them and the thick iron bank vault-style doors and window blinds installed in the living areas of the house, including in his and his wife’s bedroom and in that of their grandson’s.

This is the study where Trotsky was attacked with the infamous ice axe.

And this is one of several guard towers ringing his property.

I didn’t know this, but before Trotsky was killed with an ice axe by a guy who was able to worm his way into confidence, his compound came under a direct assault by a group of assassin commandos. They tied up some of his guards, shot up his house, injured this grandson, and maybe tried setting the place on fire. Trotsky had taken a sleeping pill that night so he was zombified throughout the ordeal. His wife — Natalia — had to roll him off and push him under their bed and even got on top of him to protect him from the gunfire. I’m guessing they installed the thick bulletproof doors after the attack, but maybe they were there from the beginning.

Here’s how Trotsky described that raid:

The attack came at dawn, about 4 A. M. I was fast asleep, having taken a sleeping drug after a hard day’s work. Awakened by the rattle of gun fire but feeling very hazy, I first imagined that a national holiday was being celebrated with fireworks outside our walls. But the explosions were too close, right here within the room, next to me and overhead. The odor of gunpowder became more acrid, more penetrating. Clearly, what we had always expected was now happening: we were under attack. Where were the police stationed outside the walls? Where the guards inside? Trussed up? Kidnapped? Killed? My wife had already jumped from her bed. The shooting continued incessantly. My wife later told me that she helped me to the floor, pushing me into the space between the bed and the wall. This was quite true. She had remained hovering over me, beside the wall, as if to shield me with her body. But by means of whispers and gestures I convinced her to lie flat on the floor. The shots came from all sides, it was difficult to tell just from where. At a certain time my wife, as she later told me, was able clearly to distinguish spurts of fire from a gun: consequently, the shooting was being done right here in the room although we could not see anybody. My impression is that altogether some two hundred shots were fired, of which about one hundred fell right here, near us. Splinters of glass from windowpanes and chips from walls flew in all directions. A little later I felt that my right leg, had been slightly wounded in two places.

As the shooting died down we heard our grandson in the neighboring room cry out: “Grandfather!” The, voice of the child in the darkness under the gunfire remains the most tragic recollection of that night. The boy — after the first shot had cut his bed diagonally as evidenced by marks left on the door and wall — threw himself under the bed. One of the assailants, apparently in a panic, fired into the bed, the bullet passed through the mattress, struck our grandson in the big toe and imbedded itself in the floor. The assailants threw two incendiary bombs and left our grandson’s bedroom. Crying, “Grandfather!” he ran after them into the patio, leaving a trail of blood behind him and, under gunfire, rushed into the room of one of the guards.

At the outcry of our grandson, my wife made her way into his already empty room. Inside, the floor, the door and a small cabinet were burning…

Trotsky survived that attempt but he was finished off a few month later by Ramón Mercader, a Spanish communist who was able to earn Trotsky’s trust and get close to him.

A funny side story is that back in the 1970s, Evgenia’s mother, Marina, casually met Mercader at a Moscow wedding party. He had gotten out of prison by then and had moved to Moscow, where he was officially received as a hero. He was an old man and hung around Spanish communist emigre circles in Moscow, which is how Evgenia’s mother met him — at a wedding party of her Spanish classmate. What’s funny is that Marina remembers that none of the young people paid him any attention. No one seemed to care that that this respectable old man in front of them was the guy who sunk an ice axe into Trotsky’s head.

It’s kinda nice that we happened to visit Trotsky’s house just as I’m beginning to write about my own family’s past. One thing I’ve started grappling with is the generic notion is that the Jews of the Russian Empire were always victims — always isolated from the general population, always suffering under the czar’s antisemitic yoke. It’s an image that has been transmitted down the generations by the masses of poor, destitute Jews that had came to America from the Pale of Settlement at the turn of the twentieth century. You can see this notion popularized in Jewish cultural productions like Fiddler on the Roof. Maybe the Jews in western Europe could be rich and assimilated, but the Jews under the Russians were stuck in their shtetls and their only real interaction with the bigger world was when some cossacks would gallop through their towns to do pogroms and rape women. It’s a black and white view of history that helps fortify the dominant mythology of Eternal Jewish Victimhood that we Jews cling to so strongly. I also think this notion appeals to the Cold War sensibilities about the irredeemable barbaric and backwards nature of Russia that dominates American culture. I myself believed in this same basic idea before I started getting deeper into this history.

Trotsky’s childhood gives a sense of a different kind of Jewish life that existed in the Russian Empire just before it blown to bits by rot and wars and revolutions. His father was born poor but was able to buy and lease a bunch of farmland from a former Russian officer in the Kherson Governorate, which was in southern Ukraine and encompassed Odessa. Reading Trotsky’s autobiography, you get the sense it was a large agricultural business and that, while there were other Jewish farmers nearby, the village that was dominated by his father’s farm existed outside of a cloistered Jewish reality. He and his parents didn’t even speak Yiddish at home, but a mixture of Russian and Ukrainian. Trotsky himself said that he had never learned speak the “Jewish language” and was as a result always disconnected from Jewish cultural life — much of which was in Yiddish.

What’s interesting is that while his parents were Jewish, they had Russian and Ukrainian workers on their farm, employing them both longterm and seasonally. And if I remember correctly they also raised pigs — which seems like a weird thing to do for Ukrainian Jews in the 19th century. What I’m trying to say is that they were very rural but basically assimilated by the standards of the day. Trotsky didn’t have to do much rebelling to kick off his family’s old shtetl identity. It was nearly gone by the time he was born, or at least that the sense he gives you in his autobiography.

One passage stood out to me about his life, and that’s when Trotsky recalls how hundreds of poor, destitute peasants would descend on his father’s farm every year to work and collect the harvest. These workers were paid little and slept out in the fields, rain or shine. Their poverty…

…This is a preview of a full letter available only to paying subscribers. Subscribe. You can do that here.

—Yasha Levine

This is part of my book, The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Read the previous installment.