This is the introduction to to Chapter Two of The Soviet Jew: A Weaponized Immigrant’s Tale. Read Chapter One here.

I’m in Mexico City right now but I started trying to write the intro to this chapter while still in our half-empty apartment in Los Angeles, surrounded by stacks of boxes and waiting for our Pod to arrive so we could put our stuff into storage. I haven’t done much writing in the last month, but I have been doing a lot of reading and a lot of thinking about how to start this next segment of my weaponized Soviet immigrant story. And having thought about it, I guess there’s really one way: to go chronologically. That means I gotta go back to the beginning. Or at least as far back as I can tell the story — which, from a purely personal family angle, isn’t very far back at all.

I come from simple old country Jewish stock. We’ve been bouncing around lands that’ve changed a lot of hands over the years. They’ve been known variously as the Kievian Rus, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Russian Empire. There are probably a few mystery places in there too, like the Caucuses or some other areas down south, given how my dad looks a little way too much like Saddam Hussain to be of purely Pale of Settlement gene pool. My ancestors had been on those lands for hundreds of years, maybe longer — long enough anyway to be basically indigenous to the region.

So we’ve been there a long time. But my own family’s collective memory goes back only a few generations. And even with the things we do know, our information is sparse. A lot of it is what I guess what you might call biblical — who begot who, who moved where, who died in what spot, who took his wife’s sister to be his mistress, that kind of thing. But I guess that’s normal. The last few generations have been through several revolutions, a civil war, and a counter-revolution, collectivization, industrialization, a major war, genocide, multiple migrations, and various cultural integrations. There’s simply been too much movement, too much churn, and few written records left behind — no letters or diaries or business records. So a lot of what we know was handed down by word of mouth — and there really isn’t even much of that. My sense is that my grandparents and great-grandparents weren’t the types of people who liked to talk about the past much. So things get hazy very quickly when you try to peer into the historical void. Still, there are a few things to say and some interesting history to tell.

Thinking about my family, I’m realizing that its two branches are sharply contrasted. One pair of grandparents — from Ukraine and Belarus — was, from what I can tell, apolitical. One was forced out of the shtetl, the other moved to the big city for work. They simply went with the flow, transitioning from a Jewish dominated life in the provinces to a de-Judified, secular life of Soviet urbanism. The other pair of grandparents was different. They were true believers. They were Marxists. In the 1920s, they were active in the youth “Jewish cells” of the Komsomol in Ukraine. They were almost certainly rabidly anti-religious and opposed to the old way of Jewish life. I’m not sure if they personally took part in the war against their fellow Jews, but around the time they were young and politically active in Jewish youth communist politics, Ukraine’s Jewish Section — filled with true believers just like them — was waging an all-out battle against Judaism and Jewish life. They were shutting down synagogues, arresting rabbis, repressing the study of Hebrew. I’m sure they were fine with that and saw it as progress.

When people think about Soviet Jews — the thing that dominates the narrative today is that they were perpetual victims. First they were victims of the Russian Empire and its antisemitic politics and then they were victims of the Soviet Union, which suppressed and destroyed the rich cultural Jewish culture that existed in the Pale of Settlement before the revolution. There is obviously a lot of truth to that. But there is another big side to the story. What’s forgotten is that a whole mass of Jews were themselves at the forefront of the war against the Jews and what they saw as their reactionary, bourgeois, religious politics and culture.

What’s interesting is that, in the end, my true believer grandparents didn’t draw any personal benefit for their dedication to Marxism and the Communist Party. After the Great Patriotic War, my grandfather Aaron was transferred from Leningrad out beyond the fringes of civilization, assigned to work as a politruk — a political commissar — responsible for enforcing correct ideological discipline in a Siberian prison near the border with with Kazakhstan. It was a horrible posting, akin to a prison sentence itself and it absolutely destroyed his health and sent him to an early grave. My dad spent his first years living there in a rough log cabin just on the other side of the gulag wall (he talked about it a bit on our podcast a few months ago). My grandfather’s exile posting didn’t seem to dampen his — or his wife’s — belief in the glory of the party. They died true believers.

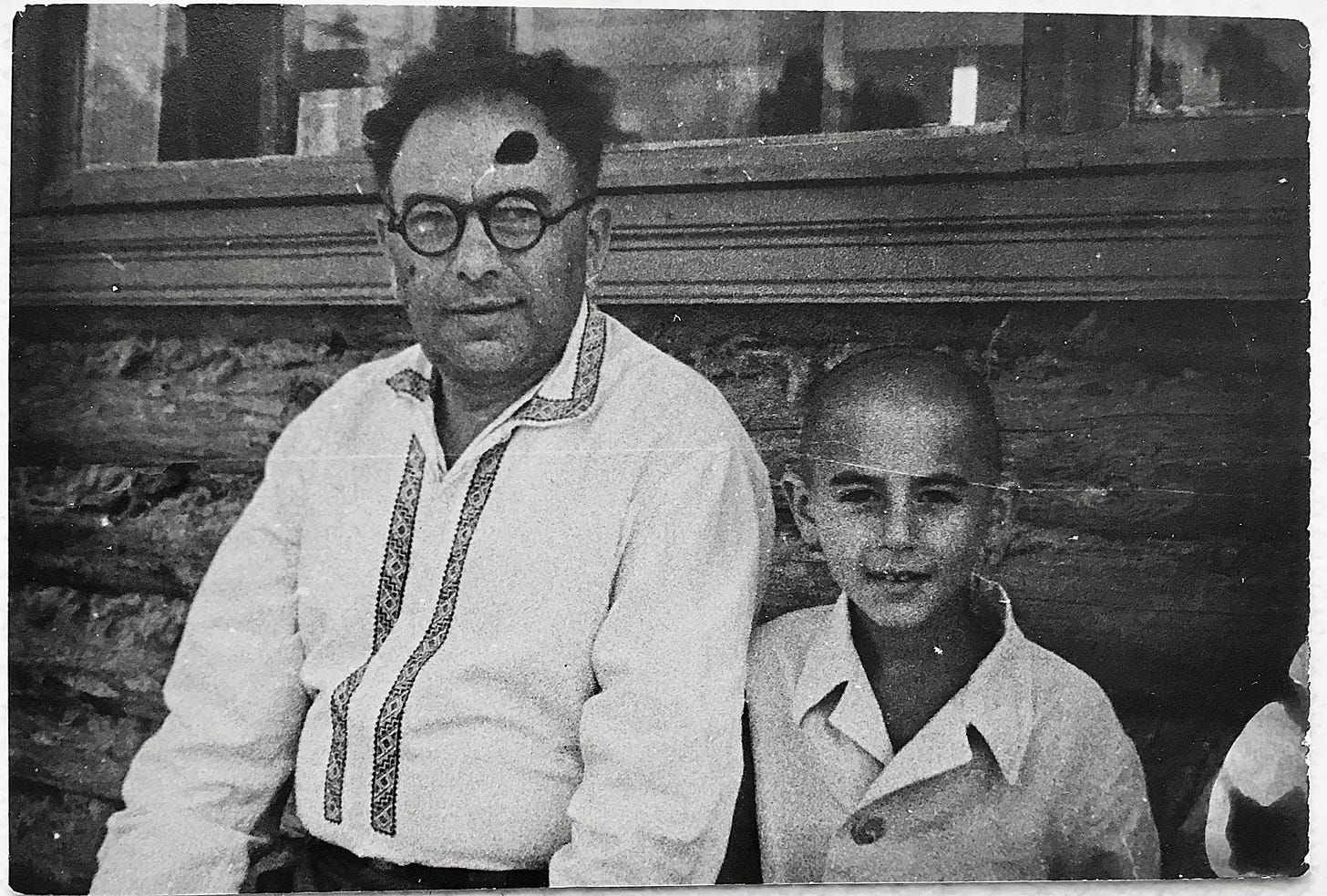

My dad with my grandfather.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I’ll write about it in next installments — beginning with my mom’s paternal side: my grandfather and his family, the Belarusian cobblers. Stay tuned.

—Yasha Levine

Love it. My own family history is very similar and equally murky.. Im really enjoying your account