Chapter One of The Soviet Jew: Part I.

I’ll be dropping all installments into this table of contents going forward. Paid subscribers get full access to all chapters and footnotes and audio versions. Read the previous bit: Introduction to The Soviet Jew: Realizing I'm part of the story.

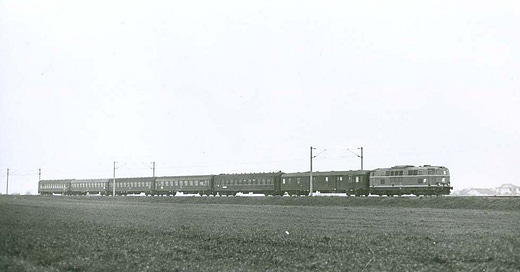

At 10:43 am on September 28, 1973, the Chopin Express pulled into a small station in the Czechoslovakian town of Bratislava, right on the Austrian border. The train, dark olive and streaked with grime, had come from Moscow and was on its way to its final stop in Vienna. It moved slowly as it approached the platform and then, with a long deep squeak, ground to a halt.

It was a cold autumn morning. People stood around wrapped in their coats, surrounded by their luggage, waiting anxiously for the train doors to open. Among the small crowd were two men who looked to be in their 20s. They had black hair and beards and minimal luggage. They showed their tickets to the conductor waiting on the platform and then climbed into the train.

Inside, the scene was immediately reassuring. It was filled with people — crying children, heaps of luggage and boxes spilling out into the corridor, the smell of salami and hard boiled eggs. It was loud and chaotic, exactly what they were expecting. They pushed their way through the train, found their compartment, and sat down in their seats. Inside with them were five others: a young couple with a small child and two elderly people.1 No one paid them any attention.

The train started with a lurch and slowly accelerated. Outside, the last bit of Czechoslovakia slipped by — fields, industrial complexes, the wide Danube River. In a half hour, the train came to a stop once again — this time at a train station outside Marchegg, a tiny town on the other side of the border in Austria. A couple of border guards and a customs official boarded and made their way through the train, checking passports and papers, poking at luggage. The two lone men felt their adrenaline kick in. Their hearts raced, their mouths went dry. The moment they had trained for, the moment that had been keeping them up at night for weeks and weeks — it was about to start.

The border officials got to their cabin and asked everyone for their passports. That’s when the men sprung into action. One of them pulled out a Bulgarian-made Kalashnikov. The other took out a grenade and an automatic pistol. They yelled at everyone to raise their hands and told the guards to drop their weapons. The two men then herded one of the guards and five passengers, including the child, off the train. Everything was going according to plan.

Then, as they made their way towards the station, something unexpected happened: the young woman with the child suddenly broke away and ran down the platform, clutching her child to her breast. At that moment, the kidnappers made a split second calculation: Let her go, the other hostages would be enough for what they needed to do.

Once inside the station, they commandeered a Volkswagen minivan, crammed the remaining four people inside, and sped to the airport in Vienna half an hour away. There — with police surrounding the airport and snipers posted on rooftops hoping for a chance to take them out — the two men began their negotiations with the Austrian government.

The kidnappers said their names were Mustafa Aoueidan and Mahmoud Khaldi and that they were members of the Eagles of the Palestinian Revolution. The issued a list of demands and warned that if they weren’t met they’d start executing their hostages.

Europe in the 1970s was full of leftwing terrorism and guerrilla activity. Palestinian groups were particularly active. Hitting Israeli targets, taking hostages, commandeering airplanes — these things were almost as a matter of routine.2 The most spectacular plot, the one that shocked the world, had taken place less than a year year earlier just across the border in Germany and involved the kidnapping of members of Israel’s Summer Olympic team in Munich — and had ended with both the hostages and Palestinian kidnappers dead after a botched rescue attempt.

But this attack on the train was different. In its own way, it was historic. It was the first time that a Palestinian group had specifically targeted Soviet Jews.

The people that Mustafa and Mahmoud had dragged off the train — well, everyone except the Austrian customs official — were Jews from the Soviet Union. Yolka Baransky, 68. Her husband Chaim, 71. David Czaplik, 26.3 They had all been traveling on a train packed with other Soviet Jews and all were on their way to Vienna, where Israeli officials were supposed pick them up, house them temporarily at a secure castle, and ultimately route them by air to their final destination: Tel-Aviv and Israel.

Why target Soviet Jews? And why in Austria?

The reason was simple. Mustafa and Mahmoud believed Israel was using Soviet Jews as a weapon in its war against the Palestinian people — and that Austria was complicit.4

They weren’t wrong.

To be continued.

A few notes for subscribers…