Since we recorded an episode on Stewart Brand last week, I thought I’d throw up a portion of my book — Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet — that deals with him. As I explained on the podcast, he’s a minor but important character in the history of the internet. His biggest contribution was in the branding department: he was part of a movement that originated here in the San Francisco Bay Area to take a counterinsurgency and surveillance technology that was being developed by the Pentagon and imbue it with the radical spirit of the counterculture.

According to Brand and people like him, computers were no longer about centralized domination and control, which was the mainstream belief in American culture all through the 1970s. Computers were about individual rebellion and empowerment. “We’re gonna topple the Man with the cool computer tools that the Man himself built, man!”

Yeah, right. How’s that going for us?

Anyway, enjoy this excerpt from my book. I took it out of Chapter 4: Utopia and Privatization.

—Yasha Levine

Hippies at ARPA

From Stewart Brand’s 1972 article for Rolling Stone magazine.

October 1972. It’s evening, and Stewart Brand, a young, lanky freelance journalist and photographer, is hanging out at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, an ARPA contractor located in the Santa Cruz mountains above the campus. And he is having a lot of fun.

He’s on assignment for Rolling Stone, the edgy house magazine of America’s counterculture, partying with a bunch of computer programmers and math geeks on ARPA’s payroll. Brand is not there to inspect computerized dossiers or to press engineers about their surveillance data subroutines. He is there for fun and frivolity: to play SpaceWar, something called a “computer video game.”

Two dozen of us are jammed in a semi-dark console room just off the main hall containing AI’s huge PDP-10 computer. AI’s Head System Programmer and most avid Spacewar nut, Ralph Gorin, faces a display screen. Players seize the five sets of control buttons, find their spaceship persona on the screen, and simultaneously: turn and fire toward any nearby still-helpless spaceships, hit the thrust button to initiate orbit before being slurped by the killer sun, and evade or shoot down any incoming enemy torpedoes or orbiting mines. After two torpedoes are fired, each ship has a three-second unarmed reloading time.

Playing a video game against other people in real time? Back then, this was wild stuff, something most people only saw in science fiction films. Brand was transfixed. He had never heard of or experienced anything like that before. It was a mind-expanding experience. Thrilling, like taking a gigantic hit of acid.

He looked at his fellow players squeezed into that tiny, drab office and had a vision. The people around him—their bodies were stuck on earth, but their minds had been teleported to another dimension, “effectively out of their bodies, computer-projected onto cathode ray tube display screens, locked in life- or-death space combat for hours at a time, ruining their eyes, numbing their fingers in frenzied mashing of control buttons, joyously slaying their friends and wasting their employer’s valuable computer time.”

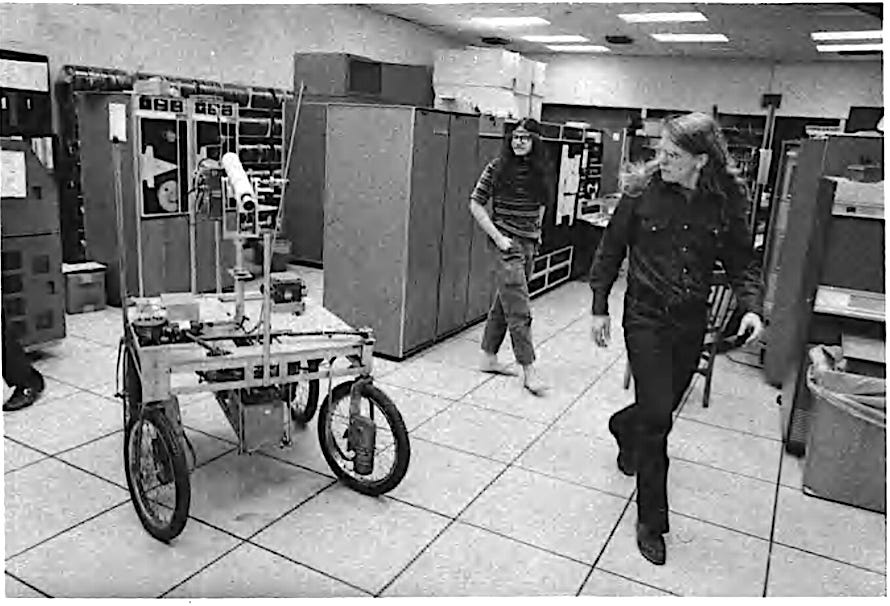

The rest of Stanford’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory was straight out of science fiction, too. While Brand and his new buddies obsessively played the video game, one-eyed robots wandered autonomously on wheels in the background. Computer-generated music filled the air, and weird lights projected on the walls. Was this a military-funded Stanford computer lab or a psychedelic Jefferson Airplane concert? To Brand, it was both, and much more. He marveled at “a fifteen-ring circus in ten different directions” going on around him. It was “the most bzz-bzz-busy scene I’ve been around since Merry Prankster Acid Tests.”

At the time, the atmosphere around Stanford was charged with anti-ARPA sentiment. The university had just come off a wave of violent antiwar protests against military research and recruitment on campus. Activists from Students for a Democratic Society specifically targeted the Stanford Research Institute—a major ARPA contractor deeply involved in everything from the ARPANET to chemical weapons and counterinsurgency—and forced the university to cut official ties.

To many on campus, ARPA was the enemy. Brand disagreed.

In a long article he filed for Rolling Stone, he set out to convince the magazine’s young and trend-setting readership that ARPA was not some big bureaucratic bummer connected to America’s war machine but instead was part of an “astonishingly enlightened research program” that just happened to be run by the Pentagon. The people he was hanging with at the Stanford AI lab were not soulless computer engineers working for a military contractor. They were hippies and rebels, counterculture types with long hair and beards. They decorated their cubicles with psychedelic art posters and leaflets against the Vietnam War. They read Tolkien and smoked pot. They were “hackers” and “computer bums... full of freedom and weirdness.... These are heads, most of them,” wrote Brand.

They were cool, they were passionate, they had ideas, they were doing something, and they wanted to change the world. They might be stuck in a computer lab on a Pentagon salary, but they were not there to serve the military. They were there to bring peace to the world, not through protest or political action but through technology. He was ecstatic. “Ready or not, computers are coming to the people. That’s good news, maybe the best since psychedelics,” he told Rolling Stone readers.

And video games, as out-of-this-world cool as they were, just scratched the surface of what these groovy scientists were cooking up. With help from ARPA, they were revolutionizing computers, transforming them from giant mainframes operated by technicians into accessible tools that any person could afford and use at home. And then there was something called the ARPANET, a newfangled computer network that promised to connect people and institutions all around the world, make real-time communication and collaboration across vast distances a cinch, deliver news instantaneously, and even play music on demand. The Grateful Dead on demand? Imagine that. “So much for record stores,” Stewart Brand predicted.

The way he described it, you’d think that working for ARPA was the most subversive thing a person could do.

Cults and Cybernetics

Brand was thirty-four and already a counterculture celebrity when he visited Stanford’s AI Lab. He had been the publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog, a wildly popular lifestyle magazine for the commune movement. He ran with Ken Kesey and his LSD-dropping Merry Pranksters, and he had played a central role in setting up and promoting the psychedelic concert where the Grateful Dead debuted and rang in San Francisco’s Summer of Love. Brand was deeply embedded in California’s counterculture and appeared as a major character in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Yet there he was, acting as a pitch man for ARPA, a military agency that had in its short existence already racked up a bloody reputation— from chemical warfare to counterinsurgency and surveillance. It didn’t seem to make any sense.

Stewart Brand was born in Rockford, Illinois. His mother was a homemaker; his father, a successful advertising man. After graduating from an elite boarding school, Brand attended Stanford University. His diaries from the time show a young man deeply attached to his individuality and fearful of the Soviet Union. His nightmare scenario was that America would be invaded by the Red Army and that communism would take away his free will to think and do whatever he wanted. “That my mind would no longer be my own, but a tool carefully shaped by the descendants of Pavlov,” he wrote in one diary entry. “If there’s a fight, then, I will fight. And fight with a purpose. I will not fight for America, nor for home, nor for President Eisenhower, nor for capitalism, nor even for democracy. I will fight for individualism and personal liberty. If I must be a fool, I want to be my own particular brand of fool—utterly unlike other fools. I will fight to avoid becoming a number—to others and to myself.”

After college, Brand enrolled in the US Army and trained as a parachutist and a photographer. In 1962, after finishing his service, he moved to the Bay Area and drifted toward the growing counterculture. He hooked up with Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, took a lot of psychedelic drugs, partied, made art, and participated in an experimental program to test the effects of LSD that, unknown to him, was secretly being conducted by the Central Intelligence Agency as part of its MK-ULTRA program.

While the New Left protested against the war, joined the civil rights movement, and pushed for women’s rights, Brand took a different path. He belonged to the libertarian wing of the counterculture, which tended to look down on traditional political activism and viewed all politics with skepticism and scorn. Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and a spiritual leader of the hippie-libertarian movement, channeled this sensibility when he told thousands of people assembled at an anti– Vietnam War rally at UC Berkeley that their attempt to use politics to stop the war was doomed to failure. “Do you want to know how to stop the war?” he screamed. “Just turn your backs on it, fuck it!”

Many did exactly that. They turned their backs, said “fuck it!” and moved out of the cities to rural America: upstate New York, New Mexico, Oregon, Vermont, western Massachusetts. They blended eastern spirituality, romantic notions of self-sufficiency, and the cybernetic ideas of Norbert Wiener. Many tended to see politics and social hierarchical structures as fundamental enemies to human harmony, and they sought to build communities free of top-down control. They did not want to reform or engage with what they saw as a corrupt old system, so they fled to the countryside and founded communes, hoping to create from scratch a new world based on a better set of ideals. They saw themselves as a new generation of pioneers settling the American frontier.

Stanford University historian Fred Turner called this wing of the counterculture the “New Communalists” and wrote a book that traced the cultural origins of this movement and the pivotal role that Stewart Brand and cybernetic ideology came to play in it. “If mainstream America had become a culture of conflict, with riots at home and war abroad, the commune world would be one of harmony. If the American state deployed massive weapons systems in order to destroy faraway peoples, the New Communalists would deploy small-scale technologies—ranging from axes and hoes to amplifiers, strobe lights, slide projectors, and LSD—to bring people together and allow them to experience their common humanity,” he wrote in From Counterculture to Cyberculture.