Prequel: Weaponizing Fascism for Democracy

I’d like to start by going back to the end of World War II — to the days when the weaponization of nationalism was just beginning to crystalize as an American foreign policy strategy.

This is an installment of an investigative series about the history and origins of America’s propaganda machine — and the central role that weaponized immigrants play in it.

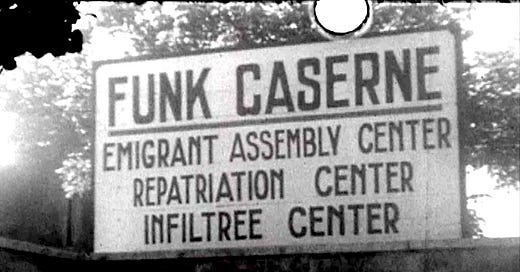

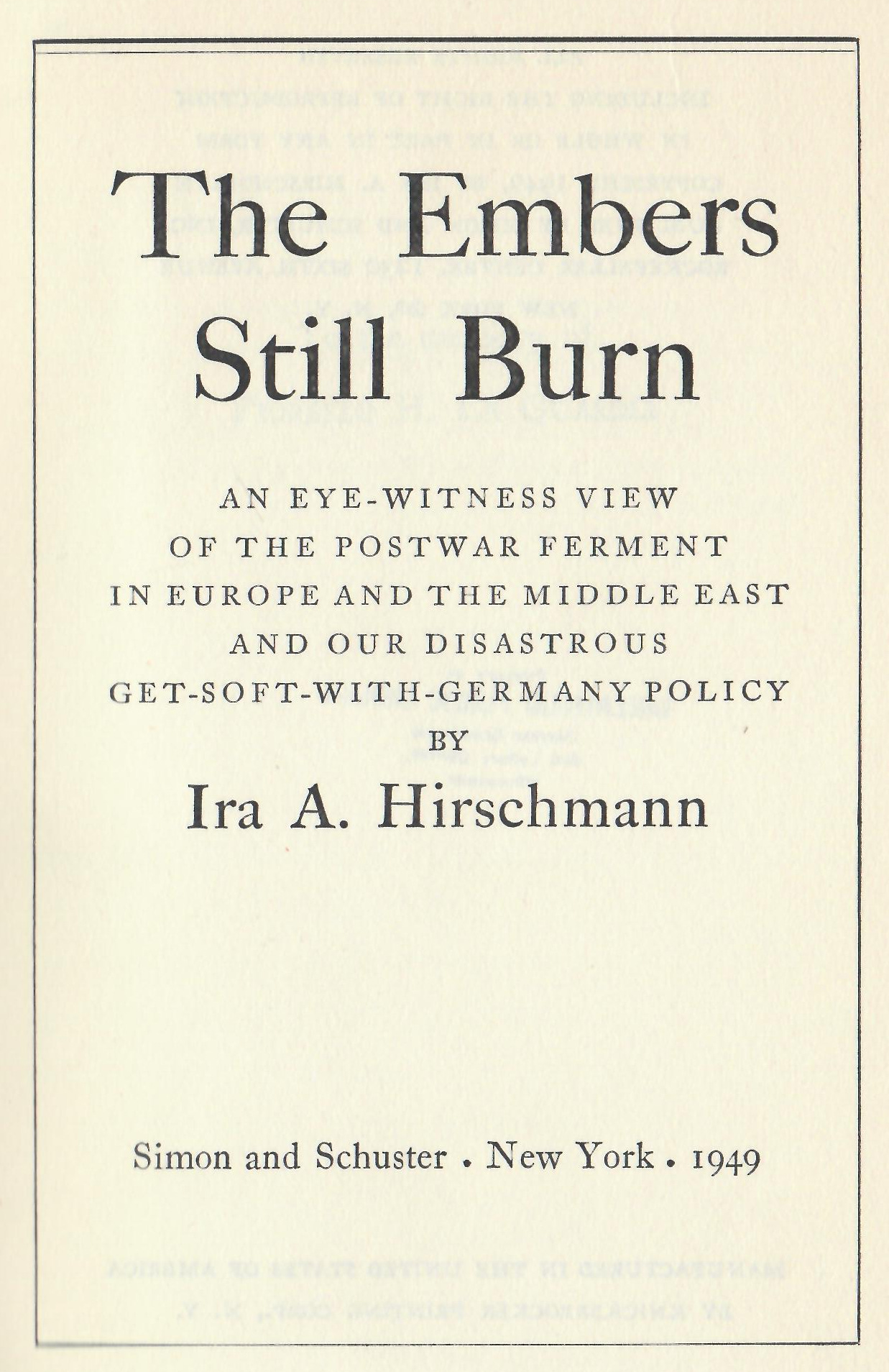

A sign outside a Jewish displaced persons camp in Munich, 1946

When I launched Immigrants as a Weapon back in September, I argued that America had done more to promote the far-right around the world than any other country on earth. I wasn’t exaggerating. America really is the biggest and most active player in the field — the biggest by far.

Even a cursory look at modern American history shows that promoting nationalism and backing far-right emigre groups has been a major plank of American foreign policy going back to the very end of World War II. This mixture of covert and overt programs and initiatives was first deployed to fight the Soviet Union and left-wing political movements but has over the years touched down all over the globe — wherever America has some sort of geopolitical interest, including modern capitalist states like Russia and China. One of these nationalism weaponization initiatives — which targeted the USSR for destabilization in the 70s and 80s — was how a Soviet kid like me ended up in San Francisco as a political refugee.

This history is important. Without it, it’s impossible to understand the mechanics of our reactionary foreign policy today — whether in China or with our “strategic partner” Ukraine, a country that’s at the center of today’s impeachment show.

There are all sorts of possible entry points into this story. I guess I could go all the way back to America’s support for the White Russians against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. But for now I’d like to start at the very end of World War II — when this approach was just beginning to crystalize as a distinct strategy inside America’s foreign policy apparatus.

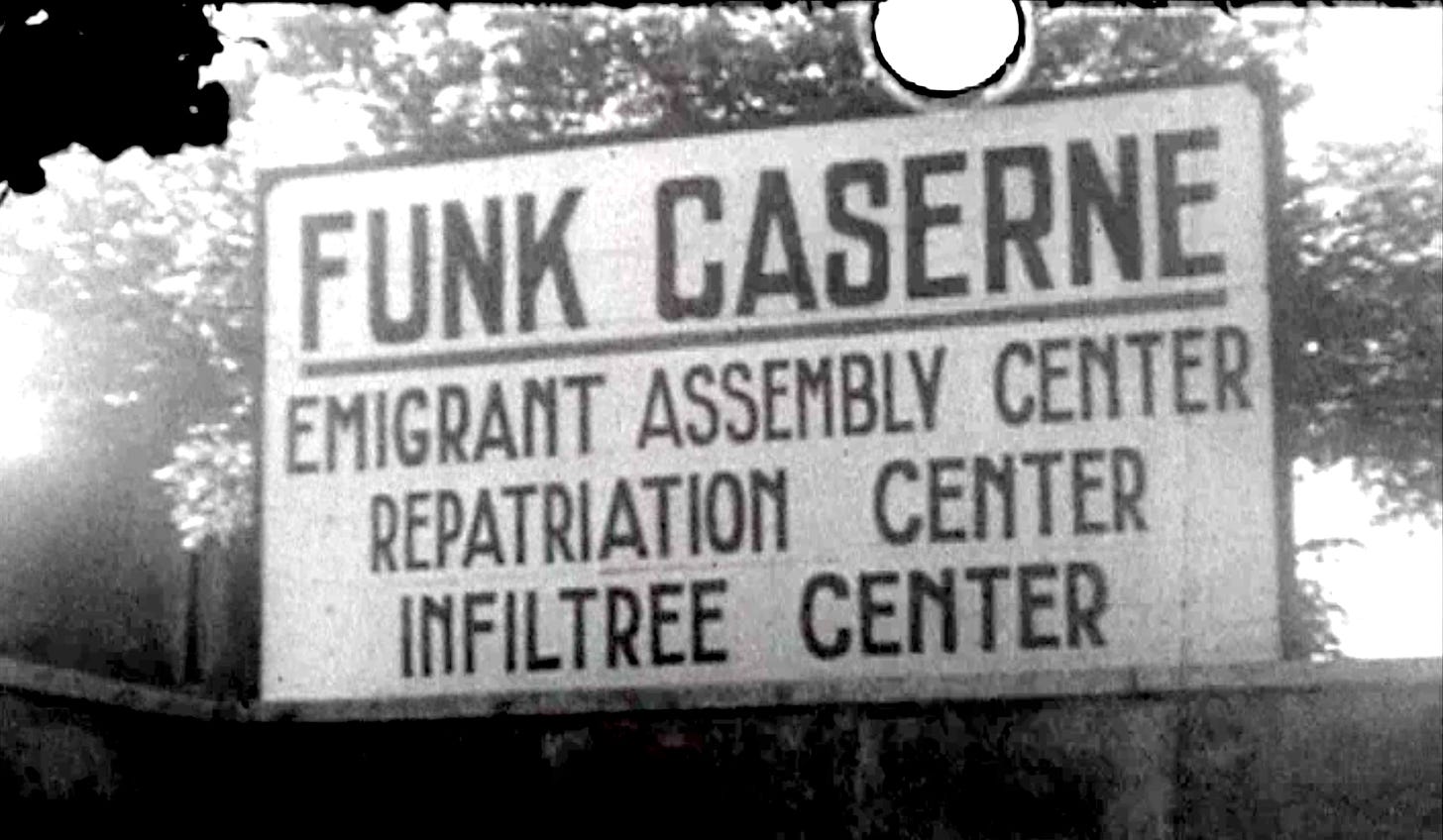

To do that I want to focus on the experiences of an American businessman named Ira Hirschmann.

Ira was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Baltimore. He started out his career in the advertising industry, moved up to running things as a department store executive in places like Saks Fifth Avenue and Bloomingdales, and then turned to liberal philanthropy, diplomacy, and Democratic Party political activism.

In 1946, he was appointed as a representative of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitations Agency — known as UNRRA — and was sent on several trips to Europe to report on how the agency was handling the hundreds of thousands of “displaced persons” who were still living in camps in Italy, Germany, and Austria.

Ira was a New Deal Man. He believed that a liberal, humanitarian world was possible. To him, the Allied victory over fascism was the starting point for this new world. America, Europe, and the Soviet Union could finally reconcile their political differences and work as partners to create a peaceful, better world for all.

But on his trips out to Europe for the UNRRA, disillusionment crept in almost immediately. He realized that the political establishment in America and Britain did not want peace but was preparing for a new war — and displaced persons camps were where this new war was bubbling up to the surface.

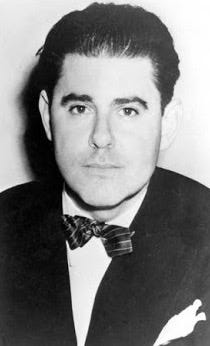

After coming back to the States he published a short, angry book about his experiences: The Embers Still Burn.

At the end of World War II, there was something like 7 or 8 million homeless people wandering around Europe. Most were quickly repatriated or made their own way back to their home countries. By 1946, when Ira came to Europe, there were still about a million people scattered through several hundred camps overseen by the UN and Allied military command.

It was a diverse crowd: Ukrainians, Latvians, Estonians, Lithuanians, Poles, Croats, Russians, Cossacks, Serbs. Poles and Ukrainians made up the biggest chunk of the “DP” population. There were Jewish survivors from all over Europe — 141,000 by UNRRA’s count in 1946.

The Jews were, of course, in a category of their own. Most of them had barely survived the war. They had been through slave death camps, spent time in hiding, or fought as partisans. Just about all of them were in a bad and feral state — psychologically and physically traumatized and depleted. And they were also totally alone. Their families and friends and communities were slaughtered during the war. They wanted to leave Europe but no one wanted to take them. America was too antisemitic to open its doors and instead was trying to force the British to send them to Palestine. In the meantime, they were stuck in limbo and needed all the extra help and care they could get.

But they weren’t getting it.

Touring the camps, Ira was horrified to learn that more than a year after the war had ended, tens of thousands of Jews who had survived genocide were still living in filth — conditions that were scarcely better than those of Nazi concentration camps.

He described a facility in Munich, an abandoned Luftwaffe garage known as Funk Caserne.

Wherever he went in Germany, Ira saw similar problems.