TikTok, imperialism, and the end of internet utopianism

To me the most interesting part of this ban is that it shows that Internet utopianism is pretty much dead. Don’t know about you, but the sooner we bury that corpse the better.

You’ve probably heard about this whole TikTok business. Donald Trump has given the company 45 days to either sell itself to an American firm or be banished from our borders. So it looks like TikTok is going to be forced to sell to a bunch of drooling Silicon Valley oligarchs for pennies on the dollar. “Nice viral app you got there, kid. Would be a shame if something were to happen to it. Hey, we just want to help out!”

A bipartisan War With China campaign has been building for quite a while now, so something like this ban was just a matter of time. What’s incredible is how many influential people on the prog-left are cheering it on.

Ryan has gone full pro-empire and is totally on board with Donald. But I guess it shouldn’t be surprising.

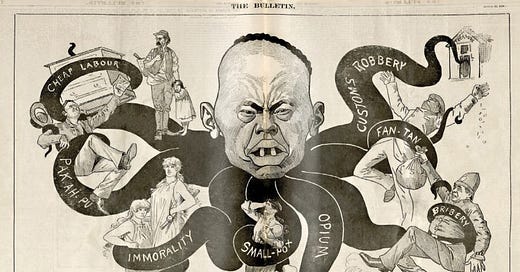

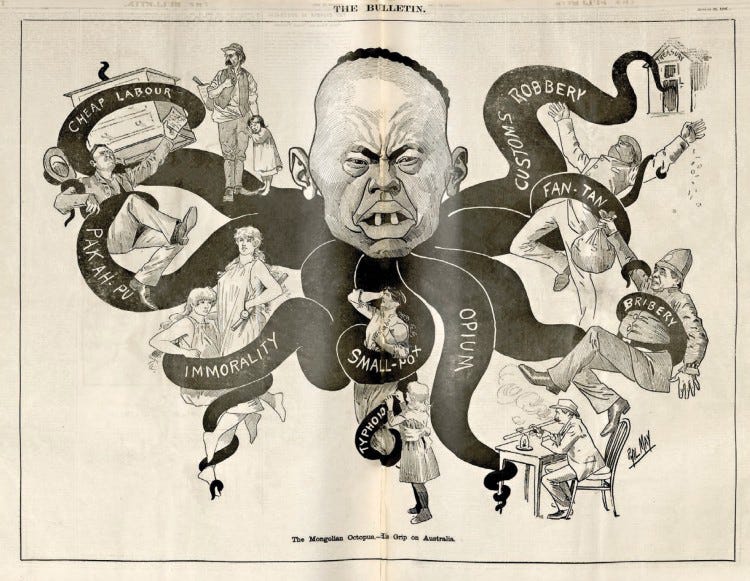

There’s a coalition of prog-type journalists and political activists in DC — many of them centered around The Intercept and Matt Stoller’s elite-driven antitrust movement — that’s been pushing for a clash with China. Some of them, like Matt and Ryan, really believe that China is like Nazi Germany. Matt has called the Chinese Communist Party the “modern Nazi Party,” while Ryan has compared China to a “new Nazi Germany” and called it “a techno-fascist government with perhaps millions in concentration camps.” If you ask me, all this is not-so-subtle code for “we must go to war with China.” What other response to can there be to a techno-fascist Nazi Germany with millions in concentration camps? We must stop these shifty fascist asians from wrapping their tentacles around the rest of the planet!

The Bulletin, 1886

I’m going to write something longer about the politics surrounding the TikTok ban as the story evolves, but I want to get a few quick thoughts down on paper now.

To me the most interesting part of this ban is that it shows that Internet utopianism is pretty much dead. Don’t know about you, but the sooner we bury that corpse the better.

From the start of the dot com boom, Silicon Valley and America’s political elite has done a great job of marketing the Internet as a totally new type of technology — a utopian system that’s removed from American imperial and business interests. Google? Facebook? Apple? eBay? These companies aren’t extensions of American imperial power. No way! They’re neutral technological platforms involved in connecting and empowering people. They’re serving users with digital democracy, regardless of their nationality or politics. They’re post-ideological and post-historical!

For a long time a lot of people believed this sales pitch. Even Silicon Valley bought into its own hype.

Of course, this idea of technological neutrality was itself extremely ideological and underpinned by massive historical revisionism. As I show in my book Surveillance Valley, the Internet has always been an instrument of American economic and military power. The Internet has always been a weapon — ever since it was developed by Pentagon in the 1960s and then unleashed on the world in early 1990s.

This ban of TikTok proves my point.

But there’s something bigger going on, too. It shows that no one really believes in Silicon Valley global utopianism anymore.

Read reporting on the issue and you’ll find that a kind of paranoid realpolitik prevails these days. No one talks about the Internet being a post-political platform. Now it’s all about how technology can be weaponized by a rival power againstAmerican interests. If an Internet company is Chinese, it naturally must be an extension of Chinese national power. If a company is Russian, the Russian government must be benefitting from its use somehow. And if a company is American — like Google or Facebook — it of course must pledge allegiance to American imperial interests. And Google and Facebook publicly agree.

The logic makes a lot of sense — and represents the hard reality that has always underpinned information technology. But what’s surprising is that is also represents a total reversal in American political culture.

From the moment that computer networking emerged in consumer culture, everyone believed in openness. It was a fundamental religious tenet of the Information Age.

From Al Gore to Newt Gingrich to Wired magazine — the consensus was that open networks, like open markets and free trade, would create a new global order that would topple monopolies, decentralize political power, and usher in a direct worldwide democracy that would render governments obsolete. Laws limiting or censoring networking technology were seen as an attack on the principle of democracy itself. This notion was endorsed in a landmark Supreme Court ruling striking down the Communications Decency Act of 1996, a law that sought to regulate obscene speech online.

Writing the majority opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens praised the network as “a vast democratic fora” — a unique new medium that brought Jeffersonian Democracy into the 21st century. “This dynamic, multifaceted category of communication includes not only traditional print and news services, but also audio, video, and still images, as well as interactive, real-time dialogue,” he wrote. “Through the use of chat rooms, any person with a phone line can become a town crier with a voice that resonates farther than it could from any soapbox. Through the use of Web pages, mail exploders, and newsgroups, the same individual can become a pamphleteer.”

When the internet went global, this belief in openness became a central plank of American foreign policy. Under the banner of Internet Freedom, first formulated and put into practice under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the U.S. championed an unfettered global internet and has sought to isolate and punish countries — China in particular — that censored or controlled their domestic internet space and kept American companies away. “Information freedom supports the peace and security that provide a foundation for global progress,” she declared in 2010. “We should err on the side of openness…”

But as the TikTok bans shows, the internet is now too free. It’s too democratic for its own good. It needs to be protected from malicious outside forces that seek to undermine its democratic potential.

What changed?

As I’ve written before, the erosion of America’s religious belief in Internet Freedom began in earnest with Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016 and Russiagate, a conspiracy theory that was unleashed to cover for that loss. But with China and Trump, this ideology of openness and unfettered democracy is reaching a whole new level of disintegration.

Part of this has to do with the fact that America’s elite feels threatened by a rising power. But I think an even bigger issue here is the need to displace blame. Our political and business elite has presided over stunning levels of national decline and degradation. America is falling apart. And someone has to take the fall. So our ruling class has desperately tried to shift blame away from themselves and onto sneaky and dangerous foreign enemy — aka the Chinese and the Russians. And the Internet has been a perfect virtual reality canvas for this xenophobic campaign. You can project anything you want on it.

That’s it for now. I’ll write more about this later. Take care.

—Yasha Levine

UPDATE 12/9/2020: In an earlier version of this piece, I wrote that Ryan Grim, along with Matt Stoller, believes that China is like Nazi Germany. That is only partially correct. Aside from comparing China to a “new Nazi Germany,” Ryan also believes China is “a techno-fascist government with perhaps millions in concentration camps.” Ryan Grim complained and accused me of libel, so I updated the story above to better reflect his views. I strive for accuracy!