TikTok and America’s fake Internet Freedom War

All this shows the limits of American liberal values. We're “enlightened” and “open” so long as Americans perceive that we have total superiority.

Since my last dispatch on TikTok and the death of Silicon Valley utopianism, I had a chance to take a closer look at the language of Donald Trump’s executive order banning TikTok — and also WeChat. And I noticed some very familiar language — language that took me back to a simpler, more optimistic time for the American Empire.

Here are the relevant bits:

TikTok automatically captures vast swaths of information from its users, including Internet and other network activity information such as location data and browsing and search histories. This data collection threatens to allow the Chinese Communist Party access to Americans’ personal and proprietary information — potentially allowing China to track the locations of Federal employees and contractors, build dossiers of personal information for blackmail, and conduct corporate espionage.

…This mobile application may also be used for disinformation campaigns that benefit the Chinese Communist Party, such as when TikTok videos spread debunked conspiracy theories about the origins of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus.

…The United States must take aggressive action against the owners of TikTok to protect our national security.

I won’t even comment on China’s “debunked conspiracies” about COVID — which Donald’s people have been pushing via the Internet on the American people more than anyone out there. But it’s no surprise that the president sees Chinese tech as a threat to the American Way of Life. He’s not alone, either.

Just about every layer of America’s media and political class shares his view that China is a force of pure undemocratic evil that needs to have its kneecaps shot out. From the respectable prog-left, to the radical center, and the right — the push to restrict China’s incursion into America’s telecommunication space enjoys multi-spectrum partisan consensus. Everyone who is anyone backs Steven Bannon’s vision. So no surprises there.

What interesting about seeing this “the Internet is a threat” stuff put into an official presidential executive order is that for years the Chinese government has been basically saying the same exact thing: that the Internet is a dangerous weapon that can be wielded by an aggressive foreign power.

But instead of being seen as a sensible and correct position — which it was, especially in the beginning — China was mocked and criticized as a weak, authoritarian power that’s afraid of letting its people communicate freely with the outside world. “THIS IS WHAT CHINESE COMMUNISM LOOKS LIKE,” we were told. “THIS IS HOW EVIL THEY ARE!”

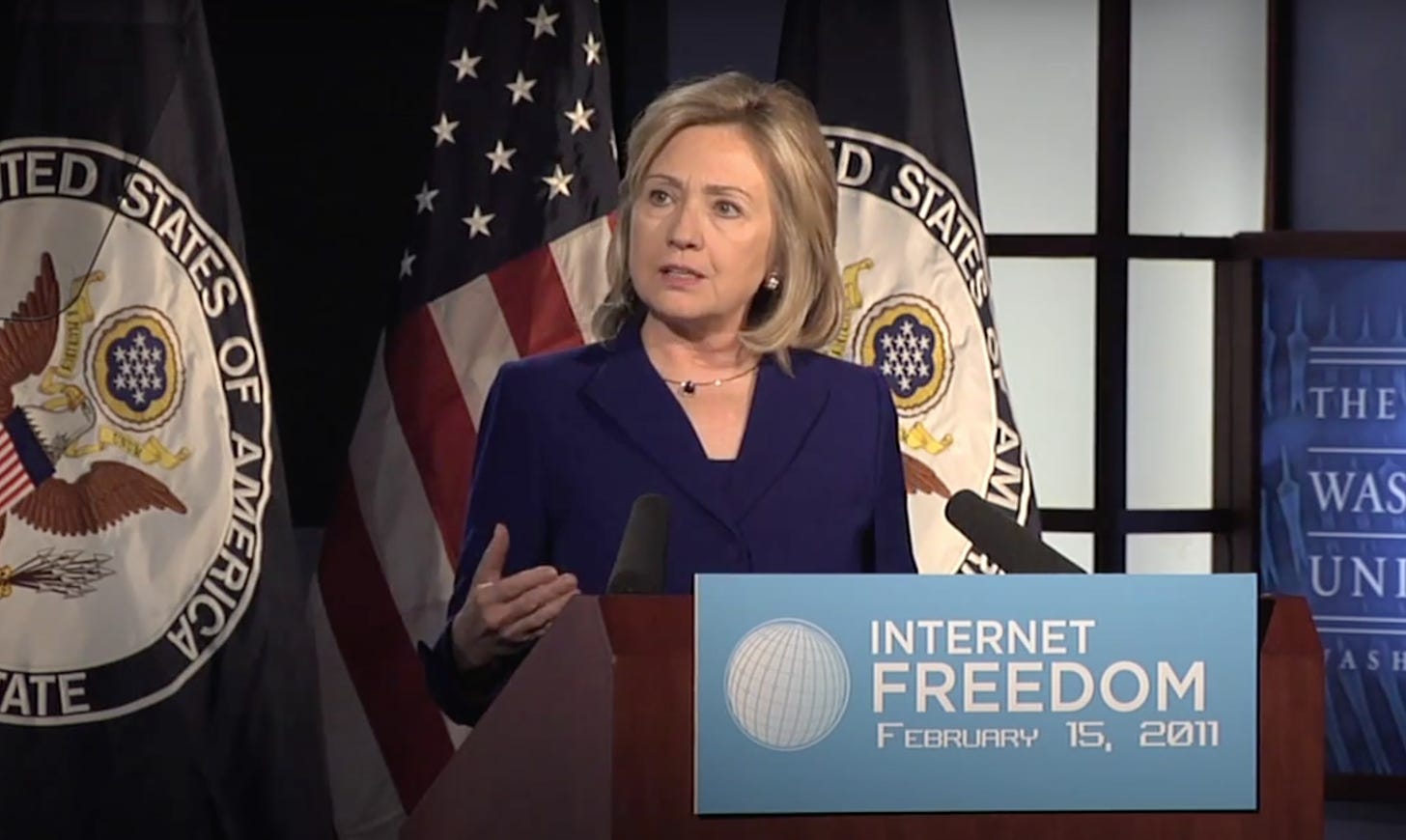

Meanwhile, as if to prove China’s point, America launched bottomless-dollar initiative to make sure China wouldn’t be able to control its own domestic Internet space. Under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, this came to be known as America’s war for “Internet Freedom” — a war which actually started back in the early 2000, when this privatized Pentagon tech first began to go global.

Today’s Hillary Clinton would call 2011 Hillary “Internet Freedom” Clinton a Chinese-Russian asset.

I devote several parts of my book Surveillance Valley to tracing the early history of this conflict. Here’s an excerpt:

Internet Freedom

The CIA had been targeting the People’s Republic of China with covert broadcasting since at least 1951, when the agency launched Radio Free Asia. Over the decades, the agency shut down and relaunched Radio Free Asia under different guises and, ultimately, handed it off to the Broadcasting Board of Governors.

When the commercial Internet began to penetrate China in the early 2000s, BBG and Radio Free Asia channeled their efforts into web-based programming. But this expansion didn’t go very smoothly. For years, China had been jamming Voice of America and Radio Free Asia programs by playing loud noises or looping Chinese opera music over the same frequencies with a more powerful radio signal, which bumped American broadcasts off the air. When these broadcasts switched to the Internet, Chinese censors hit back, blocking access to BBG websites as well as sporadically cutting access to private Internet services like Google. There was nothing surprising about this. Chinese officials saw the Internet as just another communication medium being used by America to undermine their government. Jamming this kind of activity was standard practice in China long before the Internet arrived.

Expected or not, the US government did not let the matter drop. Attempts by China to control its own domestic Internet space and block access to material and information were seen as belligerent acts—something like a modern trade embargo that limited US businesses’ and government agencies’ ability to operate freely. Under President George W. Bush, American foreign policy planners formulated policies that would become known over the next decade as “Internet Freedom.” While couched in lofty language about fighting censorship, promoting democracy, and safeguarding “freedom of expression,” these policies were rooted in big power politics: the fight to open markets to American companies and expand America’s dominance in the age of the Internet. Internet Freedom was enthusiastically backed by American businesses, especially budding Internet giants like Yahoo!, Amazon, eBay, Google, and later Facebook and Twitter. They saw foreign control of the Internet, first in China but also in Iran and later Vietnam, Russia, and Myanmar, as an illegitimate check on their ability to expand into new global markets, and ultimately as a threat to their businesses.

Internet Freedom required a new set of “soft-power” weapons: digital crowbars that could be used to wrench holes in a country’s telecommunications infrastructure. In the early 2000s, the US government began funding projects that would allow people inside China to tunnel through their country’s government firewall. The BBG’s Internet Anti-Censorship Division led the pack, sinking millions into all sorts of early “censorship circumvention” technologies. It backed SafeWeb, an Internet proxy funded by the CIA’s venture capital firm In-Q-Tel. It also funded several small outfits run by practitioners of Falun Gong, a controversial Chinese anticommunist cult banned in China whose leader believes that humans are being corrupted by aliens from other dimensions and that people of mixed blood are subhumans and unfit for salvation.

The Chinese government saw these anticensorship tools as weapons in an upgraded version of an old war. “The Internet has become a new battlefield between China and the U.S.” declared a 2010 editorial of the Xinhua News Agency, China’s official press agency. “The U.S. State Department is collaborating with Google, Twitter and other IT giants to jointly launch software that ‘will enable everyone to use the Internet freely,’ using a kind of U.S. government provided anti-blocking software, in an attempt to spread ideology and values in line with the United States’ demands.”

China saw Internet Freedom as a threat, an illegitimate attempt to undermine the country’s sovereignty through “network warfare,” and began building a sophisticated system of Internet censorship and control, which grew into the infamous Great Firewall of China. Iran soon followed in China’s footsteps.

It was the start of a censorship arms race…

I hadn’t really reread this bit since my book came out more than two years ago. Looking at it now, all the same forces and interests are still in play — and that includes the spooky Falun Gong cult that…

This is a short version of a longer piece only available to subscribers — read it here.

—Yasha Levine

Subscribe to Immigrants as a Weapon and get full access to member-only notes and letters.