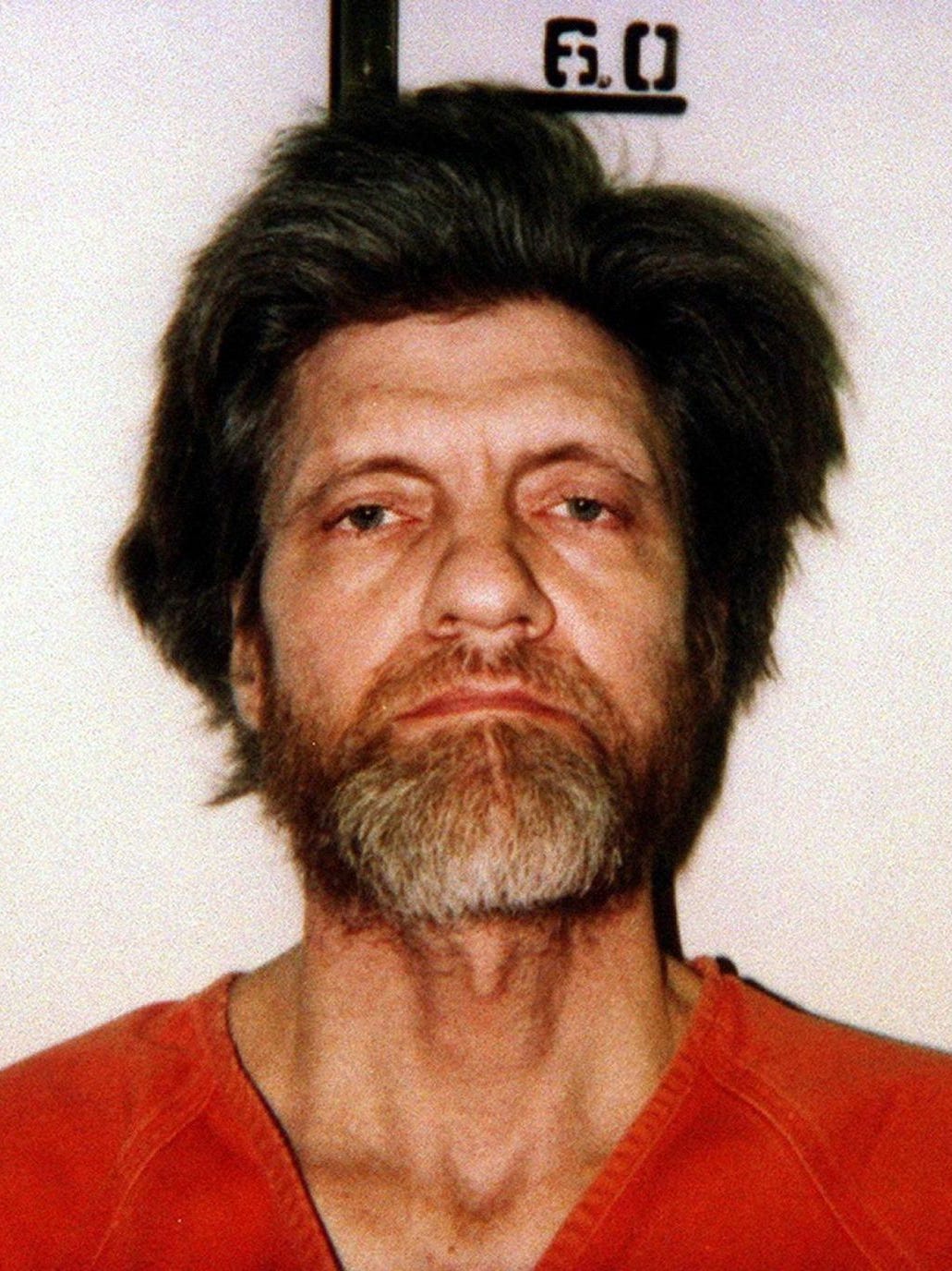

The Unabomber was wrong

I’ve been paging through Ted Kaczynski’s essays — collected in Technological Slavery — which includes his manifesto, some editorials, some later essays, as well as his prison correspondence. Overall his critique of our industrial civilization seems correct to me. But his solution — which calls for a movement to destroy the foundations of our advanced technological society — doesn’t seem like it will succeed.

A revolution against industrial technology can be successful in the longterm only if this revolutionary ideology has sway over the whole world and can stop people — any and all people — from re-developing or continuing to use industrial technologies. But for an anti-technological society to be able to police the world this way, it would have to have global reach. And something can’t be global like that without being technological to a very advanced degree. How do you maintain and enforce this anti-technological purity in a totally decentralized human world of small societies? You just can’t. Some group in some region of the world is bound to develop its own ideas and follow its own trajectory — a trajectory that might lead them embrace the old taboo devil arts of technology. Why wouldn’t they? I guess it’s what A Canticle for Leibowitz was hinting at in its own way.

So any global revolution against a technological society might succeed in the short term but it is ultimately doomed to fail — it’s within the very logic of this kind of revolution. I mean, even the Butlerian Jihad was powered by advanced technology…technology that allowed jihadists to cross space and time to kill the evil thinking machines and then enforce a ban on them across the known universe.

Just as industrialism was foisted on the world at spear and gunpoint and then maintained and expanded through increasingly centralized and global and violent organizations, an anti-technological society would have to do that, too. You’d have to stamp out any pockets of resistance and then make sure no one starts to get itchy fingers and pine for the old days of their ancestors.

I guess there’s a depressing lesson there for degrowth thinking — thinking that I very much support.

Another strange thing I noticed in Ted’s text came early in his manifesto:

3. If the system breaks down the consequences will still be very painful. But the bigger the system grows the more disastrous the results of its breakdown will be, so if it is to break down it had best break down sooner rather than later.

4. We therefore advocate a revolution against the industrial system. This revolution may or may not make use of violence; it may be sudden or it may be a relatively gradual process spanning a few decades. We can’t predict any of that. But we do outline in a very general way the measures that those who hate the industrial system should take in order to prepare the way for a revolution against that form of society. This is not to be a political revolution. Its object will be to overthrow not governments but the economic and technological basis of the present society.

Huh? A revolution against our industrial-technological society isn’t political? What’s he talking about? This is like the most radical political goal imaginable today. I sent this passage to my friend Joe Costello, who writes brilliantly about the politics of technology, and his comment was that Ted is just like everyone else in our society: “Despite his radical crazy, he still had the very traditional take that technology isn’t political, held pretty much by all.”

There are other funny things about Ted’s biases and blind spots. Despite his radical thinking about technology, he manifesto shows him clinging to the banal cultural concerns of a conservative male of his time and place. It’s obvious as soon as you start reading the manifesto. I mean, before he even gets to the meaty political part of his critique of our technological society, he has to go on and on about the gays, the feminists, the affirmative action types, leftists…pages and pages of this stuff. Feels very 90s.

He also talks about individualistic freedom in a way that sounds like it could have come out of the Mises Institute — a concept that would probably be totally alien to the kind of small hunter-gatherer societies that he advocates. I doubt individual freedom mattered much to people who lived in small bands, totally dependent on the group for survival.

So, yeah, he was a man of his time and place — if way out on the insane radical fringe. But then only insane people can be prophets. And he is a prophet in his own crazy way.

But it is funny how much he hates “the left” — even as he admits time and time again that he can’t provide a totally accurate definition of what he means by the left, that it’s more of a feeling. The left occupies a huge amount of space in his manifesto in a way that the right and the liberal center never does, despite them having the exact same problems.

For example:

Leftism is in the long run inconsistent with wild nature, with human freedom and with the elimination of modern technology. Leftism is collectivist; it seeks to bind together the entire world (both nature and the human race) into a unified whole. But this implies management of nature and of human life by organized society, and it requires advanced technology. You can’t have a united world without rapid long-distance transportation and communication, you can’t make all people love one another without sophisticated psychological techniques, you can’t have a “planned society” without the necessary technological base. Above all, leftism is driven by the need for power, and the leftist seeks power on a collective basis, through identification with a mass movement or an organization. Leftism is unlikely ever to give up technology, because technology is too valuable a source of collective power.

I mean, he is not wrong. A lot of the left — to the extent it actually exists — is still in love with industrialism and sees technology as the answer to all problems: nuclear power, more growth, more production, more consumption, air conditioners for all. Anthony Galluzzo calls this the Jetson Left. There are those, though, that are increasingly pushing for a degrowth vision for the future: cutting production, reusing what we have, living more in tune with the natural world, living outside the confines of this industrial prison we’ve built for ourselves. The number of people who are at least interested in these ideas is growing. Because let’s face it, our hyper-industrial way of life is depressing and pointless. We’re totally alienated from the environment that produced us and we’re all miserable.

But anyway, Ted’s critique of the left can be applied to pretty much any ideology of the industrial age — it spans the spectrum. The neoliberals that holds sway over most of the world today fully pushes technology as the answer to everything, all while unifying the world into one big information network market with resources and people flowing across the globe as dictated by global capital. One planet, one system, everyone connected, everyone watched and managed. That’s the logic that underpins the history I tell in my book Surveillance Valley. So it doesn’t matter if it’s capitalism or communism — most ideologies that embrace the industrial age are global in nature. That’s the technology talking.

—Yasha

Support our work. Subscribe and get access to locked podcasts and full newsletters.

Want to know more?