I’ve been brushing up on my San Francisco history lately and picked up a pretty good little book at the local shop here on Haight Street: A Short History of San Francisco by Tom Cole.

There’s an interesting bit in it about the effect that the West Coast’s first national railroad connection had on San Francisco’s economy and, as a direct byproduct, on the growth of anti-Chinese racism.

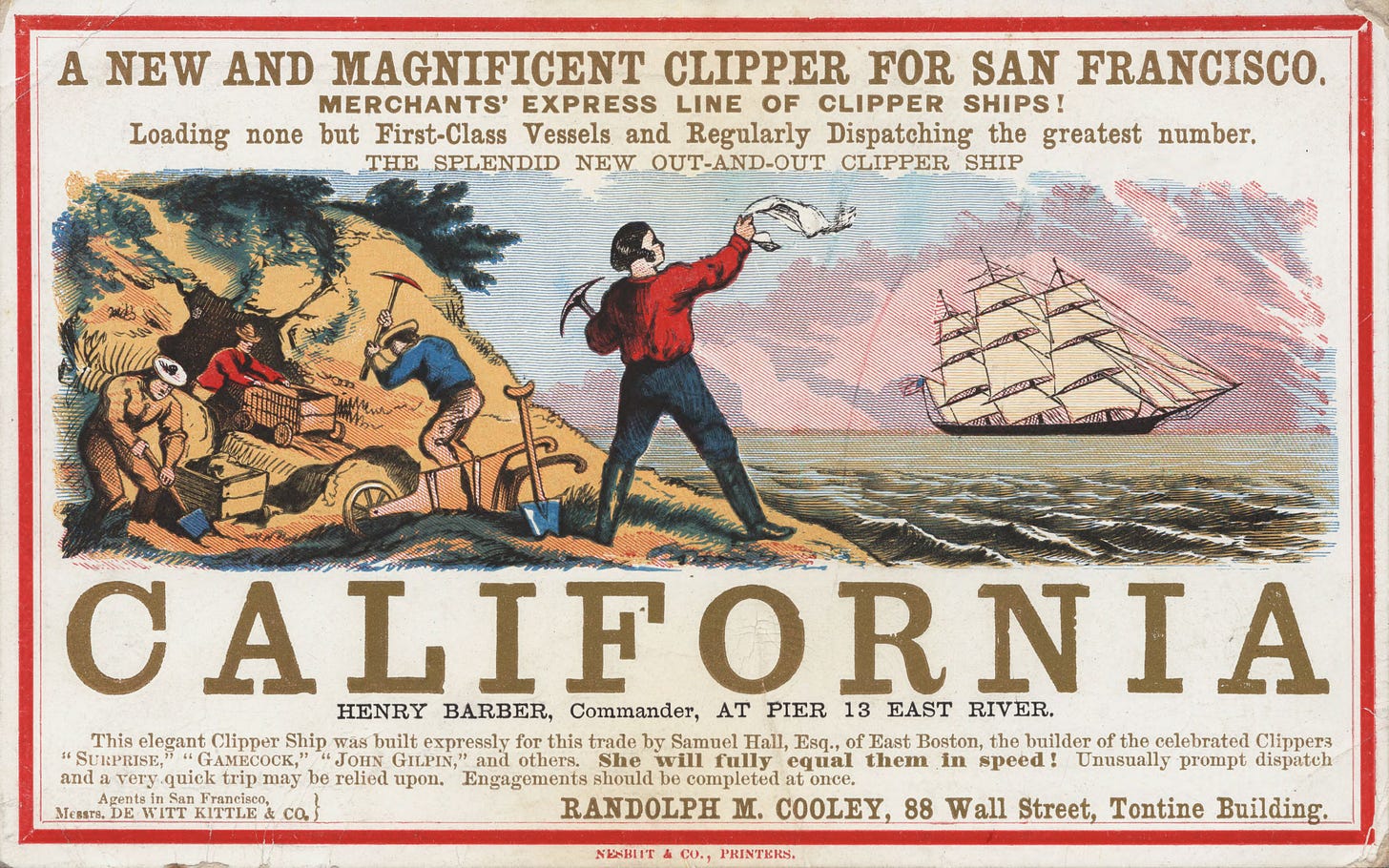

At the time San Francisco’s biggest boosters and speculators were all cheering the coming railroad technology. Until then San Francisco was not an easy place to get to. It was isolated from the rest of the world. The only to get here was either by a long and dangerous sailboat journey or a long tough slog across the midwestern plains and a treacherous hike up with all your gear and wagons over the Sierras. The railroad was gonna change all that. It was going to fold space-time and connect San Francisco to the national economy and to the world. Most of the big men who made their money off gold and silver and various speculative scams were convinced the railroad was gonna be a sure thing for them, even if they weren’t directly involved in the railroad itself. They believed it was gonna trigger yet another economic boom and make everyone even richer.

You have to remember that at the time, San Francisco could do no wrong. It had just come off two giant super nova sized booms that basically created the city: first the gold rush of 1849 in Northern California, followed by the silver rush of 1859 out in Nevada. The linking of the two coasts via railroad was happening exactly a decade after the start of the silver boom. It was supposed to keep the good times rolling for everyone.

Turned out, at least in the short term, the railroad had the opposite effect.

San Francisco had always been extremely isolated. But that isolation gave the city a lot of upsides. It protected its industries and it protected its labor power by sheer distance from the rest of America’s quickly industrializing monopolistic corporations. When the railroad was finally built, technology destroyed that protective mote. It folded space-time and foisted a kind of early globalization on the city — allowing eastern capital and industry to come in and take things over. Workers didn’t do too well in those conditions. Local factories closed, jobs suddenly vanished, while more and more workers streamed into Northern California from the east. Even the real estate market took a big dip. And the easy scapegoat? Not the technology, not corporate power. San Francisco’s Chinese residents, obviously.

Here’s the relevant bit from the book:

In the winter of 1862 Congress voted in the Pacific Railroad Act, which gave extremely low-interest financing, generous subsidies, and vast amounts of land along the right ol way to two rail companies: the Union Pacific, building from Omaha, and the Central Pacific, building from Sacramento. The genius of the Central Pacific was a young engineer named Theodore Dehone Judah, who had built California’s first railroad, the twenty-two-mile Sacramento Valley line, in 1856. For years Judah had been roaming the Sierra, surveying a rail route across the escarpment. But his plans and enthusiasm failed to ignite San Francisco’s capitalists. In 1861 Judah turned to a group of Sacramento merchants and businessmen, who in June formed the Central Pacific Railroad.

Four uncommonly crafty members of the Sacramento combine—Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, and Charles Crocker—were quick to realize the stupendous potential of their investment. They bought up and squeezed out their fellow investors, including Judah (who fought to regain control of his railroad until his death from yellow fever in 1863). The Big Four, as the sagacious ex-merchants came to be called, had captured a rolling gold mine. The federal governments haste to get the railroad built meant that not only did Huntington, Stanford et al. build the line with ridiculously cheap borrowed money, but they ended up owning vast tracts of rich western land in a checkerboard pattern on either side of the right of way. The four grew preposterously rich, moved to San Francisco, and began a mansion-building competition on Nob Hill. They treated the Central Pacific (which became the Southern Pacific in 1884) like a private money preserve. In the last four months of 1877, for example, the Big Four made the following personal withdrawals from the company’s overstuffed treasury: Crocker $31,000, Huntington $57,000, Stanford $276,000, but parsimonious Hopkins a mere $800. In time the Southern Pacific became a colossus, owner of virtually all the stated transportation companies, 9,000 miles of track and, even today four million acres of wooded, fertile, mineral-rich land. Known as “The Octopus,” the Southern Pacific and its owners utterly dominated California politics for decades.

FINANCIAL BUST

San Francisco waited gleefully as the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific inched towards each other. In April 1868, five years and three months after construction had begun at Front Street in Sacramento, the first Central Pacific train breached the Sierra at Theodore Judahs carefully chosen Donner Pass. (The crossing of the mountains had been a monumental and hair-raising bit of engineering; from then on the going was relatively easy.) Thirteen months later, on May 10, 1869, a thousand or so people met at Promontory Point, Utah, “to enact the last scene of a mighty drama of peace, on a little grassy plain surrounded by green-clad hills, with the snow-clad summits of the Wasatch Mountains looking down,” as the Alta California’s correspondent wrote. At the joining of the rails, a Golden Spike was driven, speeches made, trains whistled, and the coasts were linked.

San Francisco greeted the news with characteristic revels. The bars were jammed, the streets crowded, and some citizens carried a banner reading “San Francisco Annexes the United States.” More soberly, the Evening Bulletin editorialized, “It would be folly to say that quick communication will not stimulate trade.” That’s what they all thought—Billy Ralston, James Lick, William Sharon, the Big Four, all of them. San Francisco’s isolation had been irksome. With the completion of the railway the city could now chug to the forefront of American cities.

But an obscure writer and aging theorist named Henry George knew better. George predicted in the Overland Monthly that the expected boom would fail to materialize. He understood that San Francisco had profited in many ways from its seclusion at the continent’s edge In effect, it had been protected by a tariff of plains, desert, and mountains from the mighty factories of the East. Now those factories, George saw, would be able to flood the West with cheap manufactured goods. George saw, too, that the thousands of Chinese brought to California to work on the railroad (they were called Crockers Pets”) were soon going to occupy stage center in a terrible racist drama.

Georges predictions weie astonishingly accurate. The boom was a will- o’-the-wisp, blown through the minds of overheated boosters, men drunk on their own hopes.