Part Three: Zionists, Palestinian kidnappers, and the forced migration of Soviet Jews to Israel

The forgotten story of how a pair of Palestinian guerrillas helped liberate Soviet Jews — including my family — from being forced to go Israel.

This is part three of my story about the forced Soviet Jewish migration to Israel. Read the previous two installments: Part One: A saved Soviet Jew goes to Israel and Part Two: Soviet Jews and a Zionist Population Transfer Dream Deferred. Also read a bonus installment on Soviet Jews who fled Israel back to the USSR.

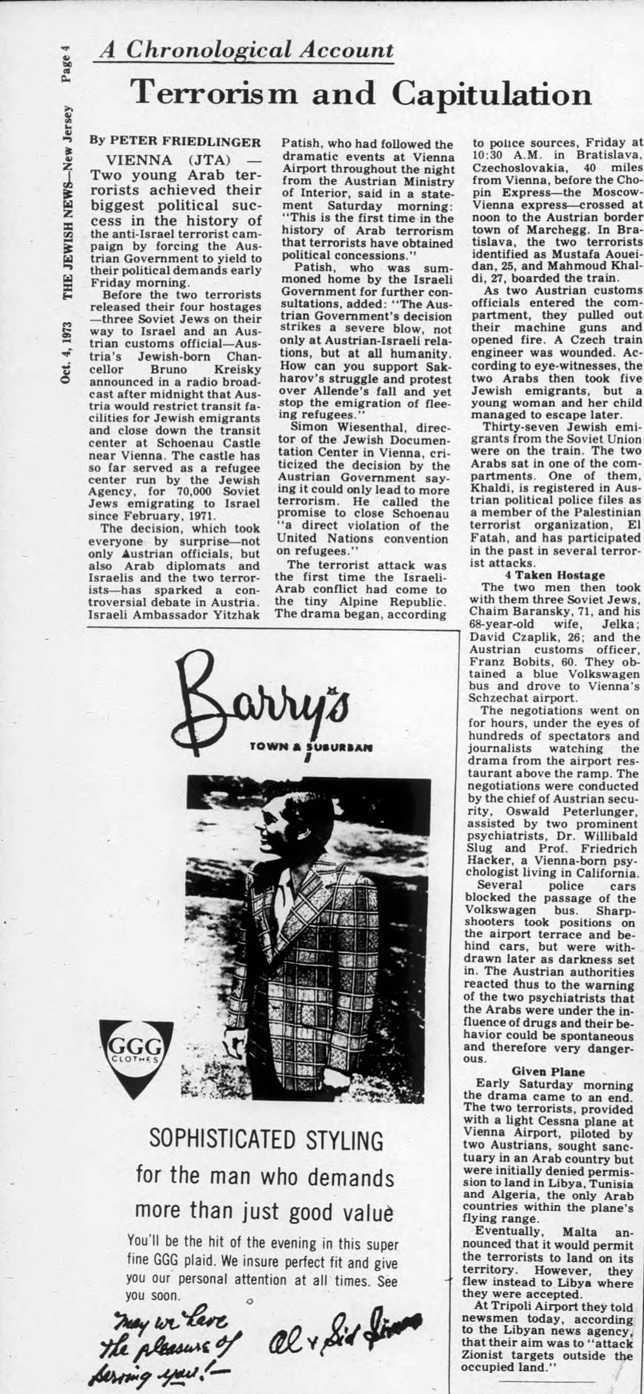

At 10:30 am on September 23, 1973, two men in their mid-twenties boarded the Moscow-Vienna “Chopin” express train at a station in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia — a town right on the Austrian border.

The train was filled with Soviet Jews bound for Israel. In this crush of families and heaps of luggage, the two men probably stood out. They were alone, were carrying minimal luggage, and they had a very obvious non-Eastern Block kind of vibe. What no one realized was that they were both Palestinian, and they were heavily armed.

They made their way to their compartment and sat down. Outside, the last bit of Czechoslovakia slipped by. The train crossed the border and came to a stop at a station right outside the small Austrian town of Marchegg. Two Austrian border guards and a Czech customs official boarded and made their way through the train, checking passports and papers.

When the officials got to their cabin and asked for their passports, the two men sprung into action. One of them pulled out a Bulgarian-made Kalashnikov. The other took out a grenade and an automatic pistol. After a short strand off, they disarmed the border guards, took several hostages, and pushed them off the train. At the station, they commandeered a Volkswagen Kombi, crammed everyone inside, and drove all the way to the airport in Vienna — which was an hour away.

At their destination, they began their negotiations with the Austrian government.

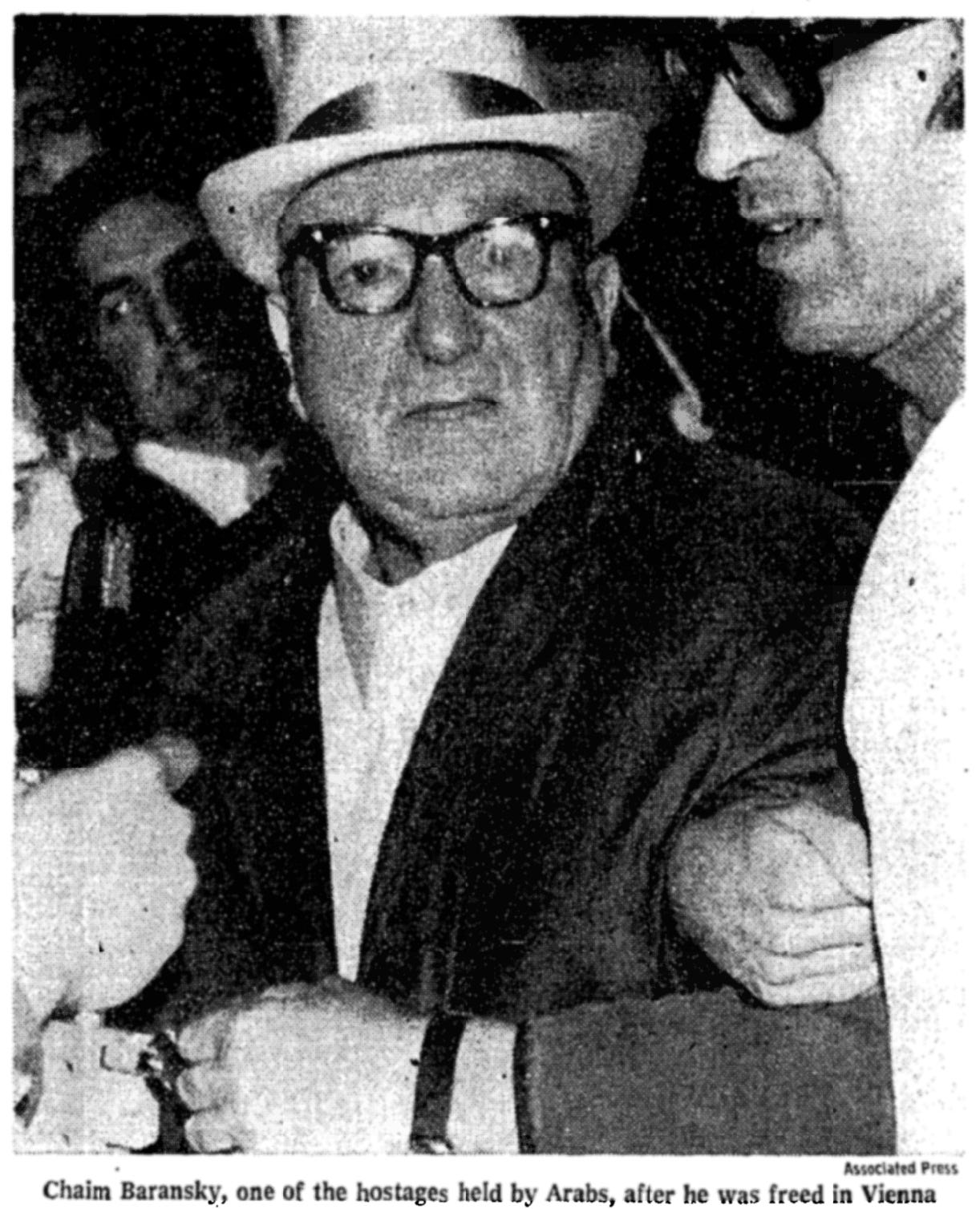

The two men — their real names were Mustafa Aoueidan and Mahmoud Khaldi — said they were part of a group called the “Eagles of the Palestinian Revolution.” They had two demands. One: That Austria immediately close down a special transit camp that was being rented out to Israel and was being used as a way-station for Jews leaving the Soviet Union. Two: That Austria provide them with a getaway plane so they can escape to the country of their choice. And if their demands weren’t met? They’d execute their four hostages: an Austrian customs official and three Soviet Jews — age 71, 68, and 26.

As Mustafa and Mahmoud explained, they were doing this because they believed Israel was using Soviet Jewish immigration as a demographic weapon in its war against Palestinian people. And Austria was directly complicit.

They weren’t wrong.

Two years earlier, in 1971, the Soviet Union had suddenly started letting out tens of thousands of Jews a year. Almost all of them were routed through Schönau, an old castle on the outskirts of Vienna that the Austrian government was letting Israel operate as an immigrant transit hub. No other country was doing this. So that made Austria a strategic chokepoint in the Soviet-Jewish weaponized-immigration-pipeline to Israel.

The goal of kidnapping was to force Austria to close the camp down, and thereby shut down — or at least slow down — Soviet Jewish immigration to Palestine. But the kidnapping was also meant to carry a message. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine — which was believed to be behind the kidnapping — wanted to highlight that the movement to liberate Soviet Jews and transfer them to Israel was an integral part of Israel’s war on the Palestinian people, and that anyone helping Israel carry out this migration was complicit and was therefore a legitimate target.

It all made sense. And to be honest, I’m surprised there weren’t more of these kinds of ops targeting Soviet Jews as they made their way to Israel through Europe.

But there was an unexpected twist to this story.

What the kidnappers didn’t realize was that while they were fighting for the Palestinian cause, they were also doing a huge favor for Soviet Jews. Their operation that day had a positive effect on the fates of hundreds of thousands of us — helping liberate us from forced migration to Israel.

My own family was directly affected. Years later, we would take a similar train out of the Soviet Union to Austria. But unlike the Jews that came before this kidnapping, me, my brother, father, and mother weren’t forced to go to Israel against our will. Thanks to Mustafa and Mahmoud, we were free to choose the country where we wanted to settle — and that was something that Israel absolutely hated, and desired to stop.

This kidnapping and its ramifications are a mostly forgotten chapter in the story of Soviet Jewish immigration. My parents didn’t know about it, neither did any Soviet immigrant living in America that I talked to. They had no idea that their freedom to choose was aided by Palestinians fighting against Israel’s occupation.

So I’m gonna tell the story.

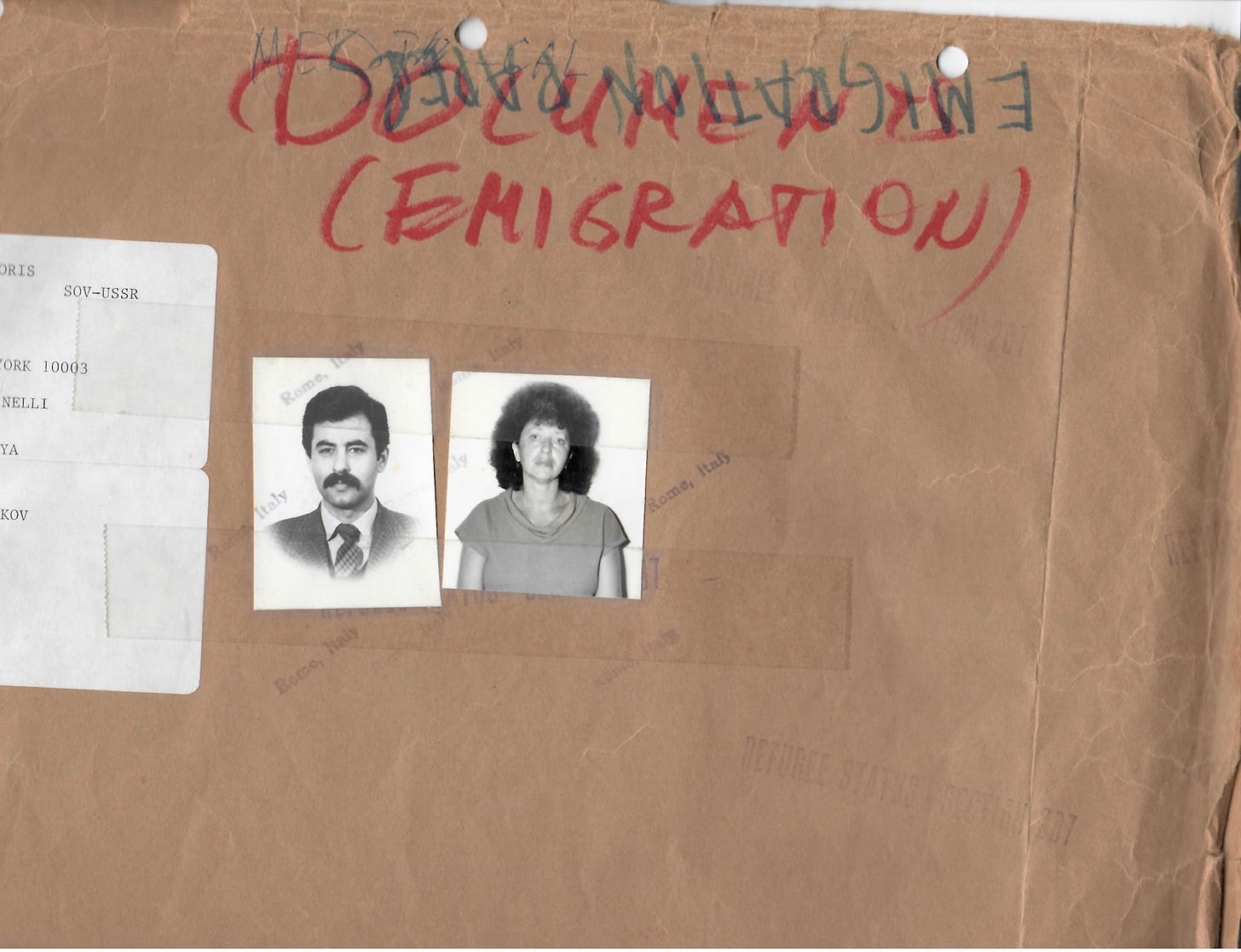

My family’s Soviet refugee document package submitted to U.S. immigration authorities in Rome in 1990 — with my parents photos plastered on the front.

As I’ve mentioned before, Israel was the first state to covertly inflame and support Jewish nationalism within the Soviet Union. From the earliest days, its leadership saw the Soviet Union’s large Jewish population as an important asset in its demographics war against the Palestinian people.

In the 1950s, Israel established a dedicated covert intelligence division called Nativ that sent in agents into the Soviet Union to make contact with Soviet Jews and proselytize Zionism. The operation was tepid at first, but it picked up after 1967, when Israel occupied the West Bank and began constructing settlements. Zionists needed a lot of Jewish (or at least Jewish-passing) bodies to fill all that newly occupied land.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, the number of Soviet Jews who were let out of the country was tiny — usually only several hundred a year, sometimes more but usually a lot less. So for years, the dream of Soviet Jews flooding into Israel was just that — a dream. But after two decades of sneaking in Zionist propaganda and working with America to pressure and squeeze the Soviet Union to let out its Jews, things began to change.

In 1971, the Soviet Union suddenly opened the flood gates. That year it let out somewhere between nine and thirteen thousand Jews — about ten times what it allowed the year before. Israel had been dreaming of this day. The prophesy was finally coming true.

For Soviet Jews, though, the process of getting out was a bit convoluted.

In 1967, the Soviet Union broke off all diplomatic relations with Israel following Israel’s surprise attack on Egypt and Syria in what became known as the Six-Day War. It would not restore them until 1991. There was no Israeli embassy in the USSR, nor were there any flights to or from Israel. Soviet Jews couldn’t just hop on an El-Al flight in Moscow and be in Tel-Aviv a few hours later.

Schloss Schönau. Pictured here in the late 19th century.

To get around this problem, Israel cobbled together a solution. The Dutch Embassy, which fronted for Israeli diplomatic interests, would issue Soviet Jews a visa that allowed them to go to Israel. But since they couldn’t travel to Israel directly, they’d have to go through a willing third-party country — and that country was Austria.

Israel hammered out a deal with the Austrian government to get access to an old castle south of Vienna that could be used as a kind of super-territorial transit point for Soviet Jews: They would arrive in Vienna by train or plane in groups of various sizes from all over the Soviet Union and live at the camp for a bit. They didn’t need visas and would be overseen by Israeli officials and guarded by Israeli security. And when enough of them would amass, Israel would charter an El-Al flight from Vienna to Tel-Aviv.

That’s how things went. In 1971 and 1972, the plan was carried out without a hitch — and somewhere around 40,000 Soviet Jews got processed through the castle and sent on to Israel.

The American Jewish World, 1972

On the surface everything was going great. But tensions were already brewing.

First was the security situation. The Austrian government wanted to keep the existence of the camp on the down-low as much as possible. Palestinian and leftwing guerrilla groups were operating at full capacity in Europe back in those days and hitting Israeli and Zionist targets. With Schloss Schönau involved in moving Jews to occupied Palestine, it was a giant red flashing light that was just begging to be hit. And that’s the last thing that the Austrians needed or wanted. But to their great annoyance, the Israelis wouldn’t listen. This was their big political moment and Israeli politicians just wound’t stay quiet about it. They wanted to show off. Golda Meir came for a photo op, so did other top Israeli pols.

The camp was being routinely covered in the Israeli and international press, so it wasn’t long before the Austrian government started getting anonymous threats. In early 1973, it even arrested three people suspected of plotting an attack on the camp but had to let them go after their comrades in Beirut threatened to bomb the Austrian embassy. In short: Schloss Schönau was a nightmare security situation. Something was gonna pop. And the Israelis were the ones who’d be to blame.

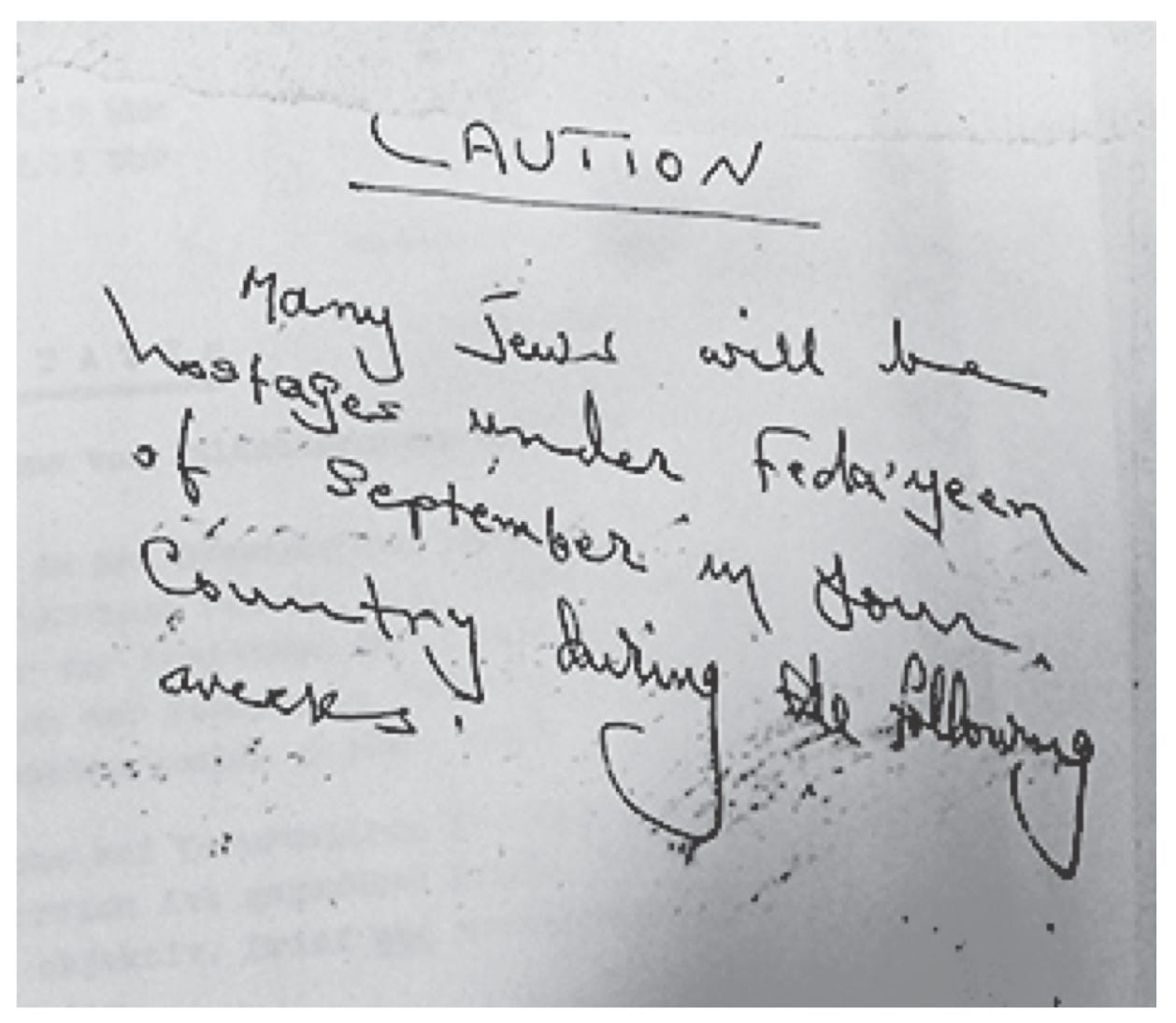

“CAUTION: Many Jews will be hostages under Feda’yeen of September in your country during the following weeks.” — an anonymous note sent to the Austrian embassy in Beirut in February 1973.

But there was something else that annoyed the Austrians.

Soviet Jews who wound up in Schloss Schönau with an Israeli visa didn’t actually have to go to Israel if they didn’t want to. There were plenty of other countries willing to take them if they wanted to apply for immigration — with the main destination being America. And the Austrian government would periodically deliver official literature to the camp that outlined the various immigration options that were available to Soviet Jews. But once the Austrians left, the Israelis running the camp would throw it in the dumpster.

The last thing Israel wanted was to give Soviet Jews the freedom to choose where they would spend their lives. Their Jewish bodies were needed in the newly expanded post-1967 Jewish homeland, not in Brighton Beach. So the Israelis withheld evidence and lied to incoming migrants about their options and generally gave the Austrians — their gracious hosts — the finger.

And this cynical and manipulative plan worked. From 1971 through 1973, Israel was able to route almost 80,000 Soviet Jews straight to Israel with minimal migration leakage to other countries.

Bruno Kreisky, Austria’s powerful Chancellor, was Jewish and should’ve been sympathetic to the Israeli position on forced Soviet Jewish migration. But he wasn’t. In fact, he was deeply annoyed and insulted. That’s because he was a type of Jewish politician that doesn’t really exist anymore. He was not a Zionist.

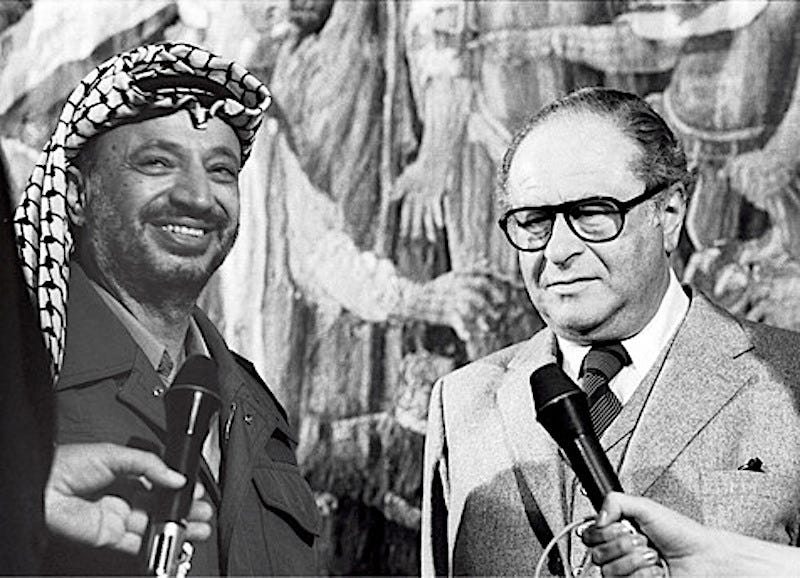

Bruno Kreisky meets with Yasir Arafat in Vienna, 1979. (Source: akg-images / IMAGNO / Votava)

Kreisky, who became Austria’s Chancellor in 1970 and remained in power for thirteen years, was born in 1911 into a wealthy assimilated Jewish Austrian family. He was active in the communist and socialist political scene in the 1930s. Like the majority of Austrian Jews, he fled the country after Anschluss. And he spent the war hiding out in Sweden. Despite Austria’s embrace of Nazism and the fact that most of the Jews who stayed were rounded up and massacred, Kreisky never became a Zionist.

As historian Kathrin Bachleitner wrote in a great essay on Kreisky and the Schloss Schönau scandal, the Chancellor believed that the fascism and the antisemitism that took over his country were purely political problems — problems that socialist politics in Austria could fix. This wasn’t something that required the establishment of a Jewish state. In fact, he was repelled by the idea of Zionism and believed it differed little from the “blood and soil” fascism of Hitler and the Nazis. He saw himself as an Austrian — an Austrian with a Jewish cultural identity. And Austria was his country. It was where his family had lived for generations. “Try as I may, I cannot see why the land of my real ancestors should be less dear to me than a strip of desert with which I have no ties,” he would later write in his autobiography.

With his lack of Zionist zeal, Kreisky believed that Soviet Jews had a right to emigrate wherever they wanted. He couldn’t get on board with how the Israelis were herding them to Israel as if they were nothing but cattle. But Israeli officials didn’t care. They disregarded the Austrians and made their own rules. They acted like the camp they were running in Austria was an extension of Israel — as if, as Kreisky would later write, “the camp in Schönau was extraterritorial.”

So Kreisky was pissed but there was little he could do. But then something unexpected happened.

In an op rumored to have been planned and overseen by the infamous Carlos the Jackal himself for the the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine Mustafa Aoueidan and Mahmoud Khaldi took a group of Soviet Jews hostage on a train to Austria. They saw Austria as complicit in the war against the Palestinian people and so they holed themselves up in Vienna’s airport and demanded that Austria shut down the Israeli-run Jewish migration camp at Schloss Schönau.

As a flier they carried explained in somewhat broken English:

By the name of the Palestinian Martyrs who had been martyred in struggling to return back, and by the name of the Palestinian Revolution. We, The Eagles of the Palestinian Revolution, declare our responsibility about this operation. We have done this mission, because of feeling that the immigration of the Soviet Union Jews form a great danger to our cause.

We haven’t done this mission because we are murderers by nature, but because of the crimes of Zionists who bombed our camps, killing our infants and children, women and olds, or when they murder our leaders by meagre methods and because they had declared that they will fight and destroy our people anywhere will be found. We have done it because we have rights, have the will of determination and decision to fight the Zionists wherever can be found, as ever as they are recruits to the enemy. It is not our first strike, it will not be the last, and nothing we will accept, but liberating our land by force…

Officials in Israel — including Prime Minister Golda Meir — counseled Bruno Kreisky against ceding to the kidnappers’ demands. They made the usual arguments: You can’t negotiate with terrorists. You can’t show weakness and give them what they want because it will invite only more attacks and plots like this in the future. As for the three Soviet Jews and the Austrian customs official who stood to be executed? Well, this was war. And you can’t fight a war without loss of life or collateral damage.

Unlike politicians in Germany, Kreisky wasn’t swayed by their arguments. He didn’t think this was Austria’s war. And the last thing he needed was a replay of the Palestinian hostage plot at the Munich Summer Olympics that happened just a year before — when a botched rescue operation by German police ended up with a massacre of both hostages and kidnappers. And anyway, Kreisky had long wanted to clean house at Schloss Schönau. So the kidnapping offered the perfect cover.

After half a day of negotiations — during which consulting psychologists concluded the two Palestinians were high on speed, were unpredictable, and could snap and kill their hostages at any moment — Kreisky agreed to their demands.

He promised to kick the Israelis out of Schloss Schönau. And he provided the two Palestinians with a pilot and a getaway plane, which they took — first bouncing around the Balkans and ultimately landing in Libya.

In announcing his decision, Bruno Kreisky made it clear that shutting down Schloss Schönau didn’t mean it was the end to Soviet Jewish migration through Austria. All he was doing, he said, was pulling the plug on Israel’s murky, extra-legal operation and putting it into the hands of Austrian officials. It was a change of bureaucracy and a normalization of the process — nothing more.