I recently found a paper I wrote for a film history class I took almost a decade ago at Hunter College on the different aesthetics of early socialist and fascist documentaries. What I wrote feels very relevant right now. Fascism is the winning ideology/aesthetic of our times and we don’t notice it as fish don’t notice water.

—Evgenia

P.S. Looks like I was a BAC already then.

Aestheticization of Politics versus Politicization of Aesthetics on the Example of Leni Riefenstahl and Dziga Vertov

By Evgenia Kovda • Originally written in 2015

It is interesting how often Dziga Vertov and Riefenstahl’s oeuvres get compared — and how frequently both are seen as propagandists for totalitarian regimes, despite being so polar in their views on film and on the role of artist in society. To see the difference in these two filmmakers we have to do it contextually. We have to compare and contrast the political systems under which they lived, and the way their films interacted and commented on those systems.

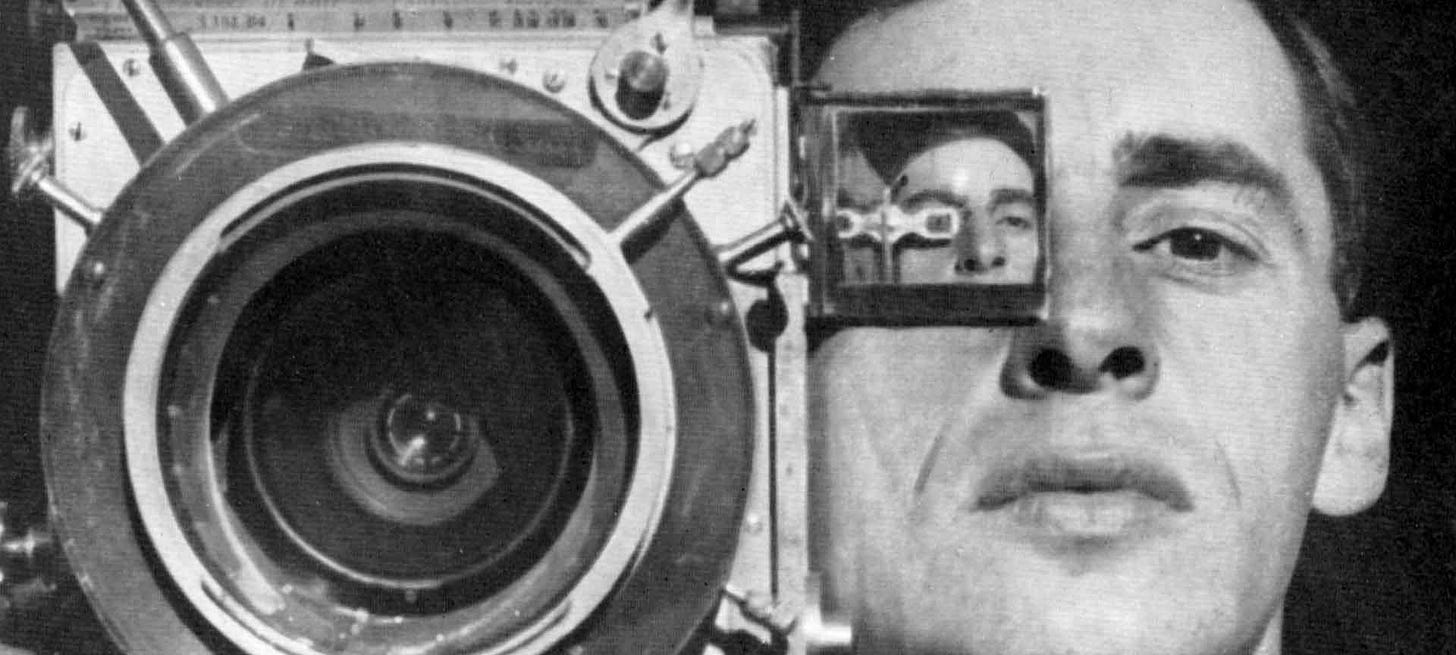

One of the most characteristic things about Vertov was that he was an ardent socialist who believed in radical democracy and saw it as something that would liberate people, empower them. He saw his goal as a filmmaker to show and illuminate truth through kinoeye — he wanted people to realize they can create their own life narrative, that they are potent and strong — both men and women — and they are part of this new society of workers who are their own masters. Aesthetically, his movies were very avant guard. But the aesthetic he created was solely to fit the content of his movies: a new society — the vanguard of potential world revolution. For Vertov, the medium is the message — as Marshal McLuhan would put it. They are not separate. Vertov sees film primarily as a political art form that fits the revolutionary times best.

Riefenstahl was a completely different type of artist. She believed in the "l'art pour l'art" doctrine, or at least that is how she defended herself when accused of being Nazi regime propagandist. Whether Riefenstahl shared popular enthusiasm for Hitler or not is in fact insignificant because her aesthetic itself is fascist.

In his seminal essay “Art `in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), Walter Benjamin talks about the inner workings of a fascist regime as having a politics of anti-politics. The goal of such a state is the mindless subjugation of the people. To him, the aestheticization of politics under fascism is unescapable, since fascist aesthetics exalt egomania and servitude, and glamorize death. According to Benjamin,

“The logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life....All efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing: war. War and war only can set a goal for mass movements on the largest scale while respecting the traditional property system…”

So art under fascism is not supposed to be political, but it should inspire and indoctrinate the masses on emotional level. That is precisely what Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” did with its inherently fascist aesthetic.

The first scene of the movie is a good example of both egomania and servitude:

Adolf Hitler’s plane is flying in the cloudy sky. It is slowly landing and we can see a well-organized marching crowd on the ground walking in perfect columns. Once Hitler comes out of the plane we can see closeups of people cheering him. They are full of joy to see the Führer even for a short moment. They are not citizens, they are devotees that would die for their Führer any moment if needed. That is the impression they give.

Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” was the first high production value documentary in the world. It was entirely sponsored by the government. Riefenstahl had a crew of 120 people and about 50 movie cameras at her disposal, as well as an almost unlimited budget for production. It is a truly epic picture. Riefenstahl was the general of that army of cameramen and proved herself very capable. The film looks extremely militaristic and well orchestrated. The movie doesn’t look as if made by an “artist of immensely naive political nature, ignorant of the outside world”. The feeling of awe it arouses is intentional. The greatness of the leader is juxtaposed with excited impersonal masses. The closeups of people’s faces are just reaction shots to the Führer’s speech to show the ecstatic state the führer puts people into.

Vertov’s fascination with Vladimir Lenin was of a different kind. He indeed saw him as the incarnation of communist ideals, and as the founder of the first communist state on earth. Yet he didn’t see Russian people as just obedient subordinated masses. He saw them as individuals too.

Vertov’s “Man with a Movie Camera”, “Three Songs About Lenin” or “Symphony of the Donbass” — none of these films have impersonal crowd shots. They show individuals who, though unnamed, have agency. They work, they do sports, frolic on the beach or sing. There is a sense of citizenry, a sense of community that aspires towards a better future. There is a feeling that people are alive and that they all are important and have something to contribute to the society.

Vertov’s “Man with a Movie Camera” has a main character: a cameraman. But id doesn’t really have any figure of authority. The filming and editing process is exposed to the viewer. Nothing is hidden. There is no deception in construction of the narrative. It creates a feeling that just like cutting the film people can also cut, move around and ultimately change the societal structure.

Vertov was a true pioneer of cinema and he was driven by his politics. Here is an excerpt from his manifesto:

“I am kino-eye. I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it. I am in constant motion. My path leads to the creation of a fresh perception of the world. I decipher in a new way a world unknown to you.”

Vertov’s aesthetics are inseparable from his political beliefs. His beliefs were firmly rooted in the promise of building a new egalitarian society, where all citizens would be an active part of it. His invention of jump cuts, his rapid montage, his peculiar camera angles — all these were at the service of a bigger political goal. It was not about unity, obedience, the preservation of order and ultimately war — like in the case of Riefenstahl. It was about the creation of a new, radically different and better world. Here lies the crucial difference in artistic sensibilities of Vertov and Riefenstahl.

The way their career unraveled in their later years is also very telling of their deep rooted artistic difference.

Vertov fell out of favor with the government after Lenin’s death. He was considered not didactic enough, too avant guard, intellectual. Under Joseph Stalin’s rule, he was ostracized and socialist realist filmmakers took the lead. Vertov didn’t even try to ingratiate himself with Stalin or change his style to fit in. He didn’t want to twist the truth. And he couldn’t be apolitical either. His art was inseparable from his beliefs. He was true to himself until the very end, despite being reduced to an editor of some insignificant newsreels. For sticking to his beliefs, he never was allowed to make another film again. He saw himself as a tragic figure: “The filmmaker without the film camera”

After World War II, Riefenstahl was to some degree ostracized because of her affiliation with Hitler and the Nazi regime. But she moved to United States and managed to live quite a comfortable life. Se was recognized as a great filmmaker who made some mistakes in the past — but those mistakes were written off as a result of naiveté rather than anything ideological. She was acquitted at the Nurnberg trial and was free to pursue filmmaking again.

Riefenstahl’s most notable post-Nazi project was not a film, but a book of photographs based on trips she made to Sudan in the 1970s. It was called “The Last of the Nuba.” Even though this is a seemingly unrelated project to her past, the continuity of her work can still be traced. Photos of the Nuba people betray her aesthetic vision once again: the glorification of well-built, strong and muscular bodies. In Riefenstahl’s photographs, the Numba do not represent ordinary humans with their weaknesses. They are supermen and women — warriors, tall, agile, fierce and courageous. They look perfectly beautiful and a bit frightening in their power — at least that is how we see them through Riefenstahl’s lens. Her photographs of the Nuba show a similar sensibility to the“Olympia” athletes or “Triumph of the Will” soldiers. Their bodies exude pure strength and confidence, they have no imperfections or weaknesses and the aesthetic of the wholes series is very much in the fascist vein — which tells us more about Riefenstahl’s politics than about the Nuba tribe itself.

The question is: Can art ever be apolitical? I doubt it. So-called apolitical art is most likely still political — but political in ways we cannot see. Which means it is in-line with the status-quo, politics that we perceive as normal. That brings up an interesting question: If people today can’t see the politics in Riefenstahl’s art, does it mean that today’s status-quo politics is fascism?

Very interesting. It seems AI produces a fascist aesthetic.

Great piece, I dont know Vertov's work, but while not being art, this made me think of Joe Rogan and the aesthetic he's cultivated. As this open minded psychonaut that is ready to listen to all sorts of people. Yet slowly thru out the years his thinking has become so far right.

The F word gets thrown around a lot now so I'm not sure if it's fascist but definitely sneaky propaganda that has swindled a ton of people it seems like. The "bro" unassumingly aestheticized politics in a big way.