While plotting out my next installment, I picked up another pandemic-related book from my local San Francisco library. It’s about how authorities handled a small bubonic plague breakout in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the first few years of the 20th century — and all the bigotry and hysteria and profiteering schemes and political fighting that came out of it.

I picked up this book because it’s related to the pandemic and to a piece of San Francisco’s forgotten early history — only later realizing that it of course it overlaps somewhat with my own immigrant project. Chinese workers here in America had a lot of similarities to the Jews of Eastern Europe and the Russian Empire: they lived in a parallel yet economically integrated world. They were forced into ghettos, were routinely pogromed, and suffered all sorts of discrimination and exploitation and had to navigate various exclusionary laws, including restrictions on owning property.

Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco’s Chinatown by Guenter B. Risse.

I’ve been making my way through it now and I think it’s probably a bit too detailed for the general reader — gets too much into the weeds of the local San Francisco situation. But even as I write this I’m thinking, “maybe not.” It’s interesting history and and it’s filled with all sorts of bits that are relevant to our own pandemic situation. Stuff like this — from the first signs of a possible outbreak in 1900:

In early January of that year a group of medical experts had expressed confidence that no foreign illness would stage a “disastrous invasion” of America because of the “sanitary improvements of progressive civilization.” Bubonic plague was considered an “Oriental disease,” lurking in contaminated Asian soil…Its bacilli were generated in filthy matter, and the disease rarely afflicted individuals adhering to new Western hygienic principles.

I swear passages like this could be describing the way American’s media and political establishment treated Covid in the beginning of 2020, when it mocked China for taking it seriously. To the people in power here, the way China reacted was a cautionary tale about the way these shifty totalitarian foreigners will use any pretext, no matter how fake or silly, to repress their citizens. There was also a lot of talk about it being a filthy asiatic disease which emerged out of gross asiatic culinary habits — remember the bat soup memes and all that? All through those early months, people took it for granted that this was a filthy Asian disease and would never make an impact here, not in our clean, democratic America!

And there’s all sorts of other stuff in the book that’s relevant to our current pandemic: the militarization of pandemic control, the role of the press in inflaming and spreading fear and hate, the suppression of information about possible plague outbreaks because the knowledge would cause a panic and hurt commerce, and the way petty local political infighting immediately blew up and shaped the response to the disease — in San Francisco’s case, Democrats and Republicans in city government fought over the budget and prevented funds from being released to do bubonic plague surveillance in the city.

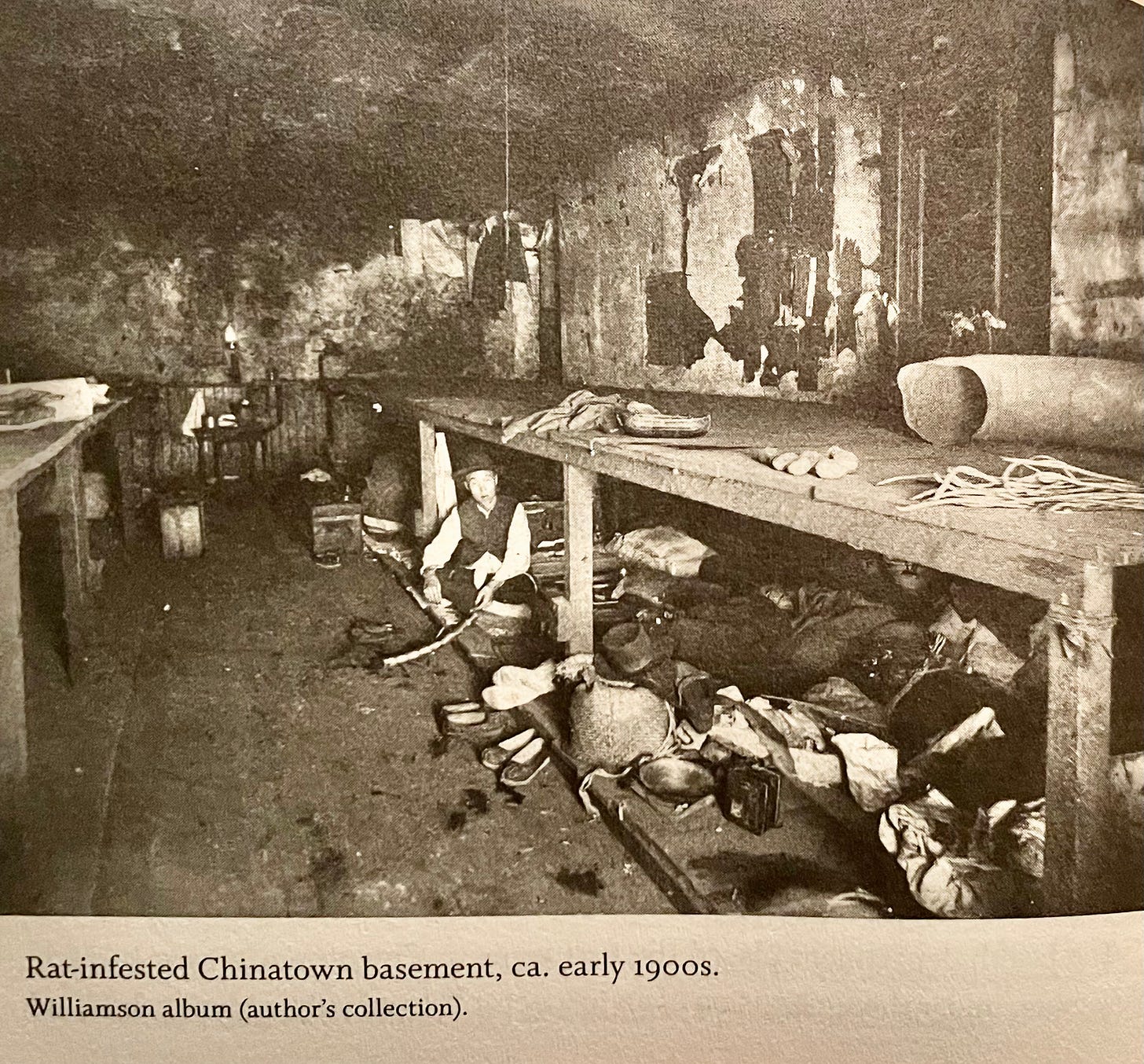

These are the kinds of conditions Chinese workers were forced to live in. San Francisco’s wealthy Anglo owners of these hovels believed the Chinese were barbaric and preferred to live like this.

But what really caught my eye was in early on in the book — in the introduction, actually. It has what is probably the most concise and readable description of the origins of the whole strange “mongoloid” racial category that emerged in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries — a category that encompasses pretty much all “non-European” easterners in Eurasia — anyone from Jews to Russians to the Chinese.

Here’s how Guenter B. Risse, the author of the book, explains this racial category: