“My thoughts on Russian culture”

Putin might be flexing Russia’s muscles in Syria and Russia in general is acting more like a powerful state in its foreign policy. But internally, culture wise, nothing has changed from the 1990s.

I’ve started to work again on the script for a film I plan to make: “Наследство” — or, Inheritance. Yasha and I wrote the first draft a few years ago and I’m reworking it a bit. It’s a Soviet zombie horror film that tries to make sense of the surreal environment in Russia today and its Soviet past. It’s a genre film, yet it’s a personal story that’s in part based on my ambivalent relationship with Moscow and my somewhat traumatic time there as a teenager. I don’t give away too much away, but the film is fantastical reflection of what it feels like for me to be in Russia. As Adam Curtis would put it, it’s an “emotional history.”

I’ve been getting into the right state of mind for the film, so I wanted to write a bit about the Russia I know.

Watching and reading the news here in America, many people get the sense that Russia is still very much the USSR, a formidable communist enemy state that’s out to destroy American democracy. The media constantly uses hammers and sickles, red banners, and Soviet imagery to describe Russia, as if America, the leader of the Free World, was still locked in combat with the Evil Forces of Collectivism.

When I was teaching at Hunter College in New York a few years ago, one of the brighter students in my film class asked me once if Russia was still communist. I was surprised and couldn’t help but laugh. But then I remembered that even Soviet immigrants here in the U.S. refer to Russia as the Soviet Union and imagine it to be no different from the place they ran away from. If former Soviets think Russia is still the evil USSR, what can I expect from Americans at large?

I even noticed that some people on the anti-imperialist left also think that Russia has a bit of its old Soviet spirit left in it. They think that Putin is out there on the world stage opposing American neoliberalism.

When I tell my friends back in Moscow that a lot of people here in America think Russia is still the Soviet Union, they can’t believe it’s true. They think I’m exaggerating. They like — and some of them even love — America, so they can’t really fathom it. This new American Red Scare — and the ongoing conflation of Russia with the Soviet Union — makes no sense to them.

The idea that modern Russians are a bunch of nefarious, retrograde communists who hate the western liberal way of life is weird and can’t be further from the truth. Many Russians shudder at the mention of socialism and equate democracy with capitalism. Most Russians I know personally hate socialism and the Soviet Union as much as the American establishment does, maybe even more so.

I was born in Moscow and lived there for first twenty one years of my life. I got most of my schooling there, including a BA in Iranian studies — which isn’t worth much here in US, unless I go work for the State Department.

I haven’t been living in my motherland for a decade now. But I do take long trips back to Moscow every year or so — sometimes twice a year. And I keep in touch with my friends and follow most of the major political and cultural events there. Every time I went back, the city seemed very lively — and was getting better every year. There was a good feeling there. The buses and subways were being modernized and expanded. There were new parks and movies theaters, cafes and art museums, and even a brand new film school. People were becoming political, joining protests movements. Things were improving, people were positive about the future, enjoying the bounty of western consumerist society.

My friends in Moscow were doing better and better, too. They were still in their 20s but some of them already had successful careers — some had switched career tracks on the fly. Things were flexible and fluid and easy for them. No one had any student debt — they got their college education almost for free. They became entrepreneurs, climbed corporate ladders, opened cafes and bars, bought apartments and dachas, travelled for six moths at a time. So while I was still very confused about what to do, had no real job, and had no straight path to follow as an immigrant in America, they were doing great. In fact they were doing much better than most Americans I knew their age.

There was a particularly intoxicating feeling you got there from being in a place where young people run the cultural side of life. You can be an editor-in-chief of a major magazine at twenty. At twenty five, you can be at a point in your career people in America only reach at forty or fifty — if they are lucky.

Russia seemed to be at the peak of its game.

So I was surprised that when I moved back in 2016 for a year and was considering staying for good to see my friends shocked at the thought. Why would I ever think of returning? Why would I come back home to this crappy Russia from America, the Promised Land, seemed to be the refrain.

They couldn’t understand any emotion but excitement about America. Excitement that was based on spending a month sightseeing in Los Angeles and New York and San Francisco and Las Vegas and going on a cross-country car trips. They thought America was real thriving democratic society — that it was a “normal” country, unlike Russia.

My friends simply did not want to hear anything negative about America. I was very annoyed with this persistent attitude. I was also annoyed by their constant complaining about their life in Russia. They definitely were not checking their privilege.

Then I started noticing something. I began to see that everything that seemed to me to be dynamic and alive and happening in Moscow only appeared that way because I had been passing through as a kind of tourist — there for a few weeks or a month and then gone again. My reading of what was going on was superficial. Once I had spent some real time at home, I started looking more closely at what was going on and very quickly realized that my positive assessment of recent Russian cultural growth was misplaced. What I was seeing wasn’t dynamism. It was stagnation papered over with derivative American cultural and material imports.

It wasn’t just the nightlife and entertainment and general consumer lifestyle stuff — like cross fit studios and boutique boxing gyms and cold press juice bars and gourmet burger joints and hip pour over coffee shops. It was also culture in general. By that I mean everything from TV shows to films to books to visual art and art galleries and museums. It all looked like a cheap copy of what was recently the rage in New York and Los Angeles — things that were already not so great to begin with, considering that today’s American culture is itself stagnant and stuck in a consumerist death trap. I mean, some of the most progressive political ideas that hit the mainstream in the last years has been a rehashing of the New Deal of 1930s combined with watered down 1960s radicalism. Even America’s preeminent global entertainment industry is stuck in a cul-de-sac, dominated by never ending film franchises, remakes, and dull algorithm-driven television series.

Back in Russia, I started referring to this Russian cultural copy phenomenon as evrostandart. Or as Russian liberals like to say it, they’re doing things “like in a normal country.”

What I found curious about this is that no one in Russia seemed to notice this evrostandart copycat phenomenon. Their colonial mindset was so internalized that it didn’t even register for them.

You can see it in the way that coolest and hippest Russians consume American entertainment content. They passionately discuss all the latest shows on HBO, and are elated if America produces Russia-themed shows like ”Chernobyl” or “Queen’s Gambit.” The coolest and hippest Russians swoon when an American TV series focuses its eye on them. They’re flattered that people in Metropole seem to be interested in them, a small people on the periphery.

This seems an embarrassing sentiment considering that Russians were at the forefront of early cinema and Soviet filmmakers were one of the best innovators and theoreticians of film theory, whose ideas are still taught at film schools all over the world.

This turn of events testifies to the general hegemony of the American popular culture. And similar attitudes can be surely found in Paris or Berlin as well. But in Moscow, this is particularly pernicious. The creative class here is obsequiously pro-American. When you hear them talk — their conversation is full of English words injected frequently with an American pronunciation. It’s considered very very trendy among the trendiest people in Moscow, even though it reminds me of the Russian immigrant parlance you hear in Brighton Beach.

My American friend from New York visited me in Saint Petersburg when I was living there, and found it embarrassing how obsequious people were to her, an American. She genuinely wondered, “shouldn’t they hate me?” “Hate you?” I replied. “Very funny — You are a native English speaker!”

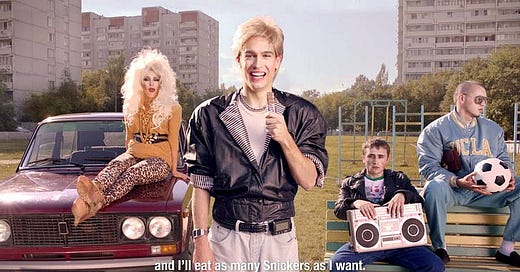

I grew up watching Tom and Jerry, Popeyes, and Disney cartoons which I preferred to the Soviet ones. I ate Snickers, Mars, Skittles. I listened to N’Sync and Britney Spears. I did all this not because I sought out to steep myself in mass American culture, but because I was naturally surrounded by it. Russia was flooded with western goods and western advertising and western cultural content. I mean, MTV Russia appeared when I was 8 and from then on I watched everything the channel showed: the new music videos, Beavis and Butt-Head and Cribs. Other Russian channels showed American films every day. I couldn’t get away from it, even if I wanted to. I remember how at 11, I watched and absolutely loved Don't Be a Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood. I didn’t understanding that it was satire. But it was funny and interesting. It felt like a window into a magical colorful faraway world.

Yet despite being surrounded by all things American, I spoke Russian and lived in Russia where it wasn’t so colorful. Moscow seemed grim and gray. It wasn’t festive like the world that America projected — like what I saw on MTV or in Don’t Be a Menace or in Olsen twins comedies. So I naturally thought of everything that was in Russia as sort of second rate — like the black and white life from those TV shopping commercial. You know the grey and frustrating image of what life is like before you buy that new blender or pillow or super sharp kitchen knife.

That was twenty years ago now. And this basic sentiment still has not changed.

Sure, Putin might be flexing Russia’s muscles in Syria and Russia in general is acting more like a powerful state in its foreign policy. But internally, culture wise, nothing has changed from the 1990s: Russia is still the colonized society, in thrall of everything western, treating every new western trend with an almost religious zeal.

Russia’s creative and liberal class feels like a new expat community in itself. Once I moved back there, I realized that they had replaced American expats, who mostly left home during the mid-to-late 2000. With them gone, Russians ran their own western-style businesses and made their own copies of metropolitan artifacts. In fact, Russians are much more effective at introducing western trends into their home country than the expats. They are well-traveled and well-steeped in everything western, and they’re also Russian and so know better what will work in their own domestic market. They don’t need people from Metropole telling them what to do anymore. They know perfectly well themselves — just copy what already exists — adapt an American show, open a chain of third way espresso shops, build out some Moscow apartments in the style of upscale Meatpacking District lofts and sell them at a ridiculous premium to a fawning clientele.

The more avant-garde clique of Moscow’s creative class might make slightly higher quality copies. But it’s still copy, copy, copy. There’s nothing else to it.

Just look at the list of the latest hit shows and films to come out of Russia: Optimists (a Mad Men ripoff), Sputnik (an Alien ripoff), Sleepers (a Homeland ripoff). I can go on and on.

There’s another thing about Russian cultural production that’s just as destructive and stagnant as the evrostandart copycatting: it does not want to look at the present.

Even the most avant-garde liberal “creators” working the scene don’t actually want to look at Russia as it is — because it’s too uncomfortable, because there’s nothing evrostandart about it, and never was beyond the tiny centre of Moscow that they’ve retrofitted in the image of a western city. They deny the importance of the October revolution and try to paint the 70 years of the Soviet Union as some kind of horrific mistake of history. They do not like to be reminded of their Soviet past or their radical two-generations-removed peasant heritage. It’s only a source of embarrassment for them. They like pretending to be some sort of royalty and align themselves with the Romanov family, which was officially canonized as saints in 2000 just when Putin took power. They’re in denial and don’t want to look honestly at their own society, so it makes sense that they’re so drawn to making shitty copies of imported western culture.

What is interesting is that the people who are in power — the Putin clan types that most of Russia’s creative class viciously opposes — have the same exact cultural values. Because they are liberals, too. And it’s the hardest thing to explain to someone who is not Russian.

The difference between the Putin’s power clique and the opposition that’s now represented by Alexei Navalny is rather minimal. It is not even cultural really — not everyone in the Kremlin is some brutish goon in a gold plated armchair, as they are often portrayed. It’s one clan against the other. The liberal clan is a bit more technocratic and has more Western MBAs under their belts. But even that doesn’t fully explain it.

The Russian political landscape is so confusing to the outside observers that it’s hard to describe it in a straight manner. I think Imaginative fiction does a much better job. The 90s Russia is best captured by Victor Pelevin in his novel Generation P — or, Homo Zapiens. While Russia today seems to elude all the Russian writers for now. No one really pinned it down well. Vladimir Sorokin tried to portray Russia of the mid-oughts as a semi-medieval brute monarchy in his satirical novel Day of the Oprichnik, and there is some truth to it. But even Sorokin — the best that Russia’s liberal creative class has to offer — misses the mark. Because he fails to see that Putin’s people are actually like him.

Surveying Russia’s cultural scene, I can’t really find a single recent film or book that reflects the schizophrenic reality of Russia today. It’s something I’m trying to fix.

—Evgenia Kovda

PS: Tomorrow Yasha and I are releasing a new podcast ep where we talk about this issue more broadly. Stay tuned.

Good luck on your film Evgenia! It sounds so amazing and one of my favorite genres. I am also so looking forward to listening to this new episode with my mom as we drive cross country on my exodus out of LA.

I am in a very close relationship with a Moscow boy who lives in the US now too and you pinpointed the mood perfectly -- the grim black and white portion of life before you get the new blender. We endlessly butt heads over this as he constantly complains about how terrible Russia is because he still wants to believe in the illusion presented of America. I, on the other hand tell him -- well look -- we've got the new blender, but that doesn't mean much of anything with my $50k in student loans and inability to afford a home or have healthcare.

I don't want to pretend to know what life is like in Russia, I just get infuriated by the claim that America is so great cause of these new blenders haha. As always appreciate your reads on this topic and this one particularly makes me feel more sane!

Thank you Evgenia for this thoughtful piece. I'm much older than you, and I have watched the hollowed-out "culture" of consumerism masquerading as "democracy" and "capitalism" spread from my native California into Russia, China, India -- literally everywhere. I have been living for the past 45 years in a self-congratulatory "beach town" with its own branch of the University of California and outposts of Google and Amazon nestled above glittering lifestyle emporia that claim to be successors the funky surf shops of old. It's all a lie here, just like it is in Moscow.

I'm leaving, because I can sell my grossly inflated house to people who think that they can "consume" our non-existent "California beach culture," and have enough to get by in a more rural place -- one still blighted by our hollow consumerism, but less certain of its worth.