There’s а tendency to fetishize big cities. To a lot of people, they’re the answer to all our problems: they’re dense, walkable, can have good public transportation, they’re easier to organize politically, they’re supposedly sustainable and green. So the bigger and denser they are, the better for everyone. Build up and up. No limits! Rarely, if ever, do I see anyone talk about their destructive side.

There’s a great book from a few decades ago that looks at this issue from the perspective of the city where I grew up: Imperial San Francisco by Gray Brechin.

San Francisco was a boom town built on a mining frenzy — first the Gold Rush, then the Silver Rush that followed a decade later. This race to extract riches from the earth launched a massive population transfer and led to frenzied industrial development that leveled much of the natural world around San Francisco — a mad dash to build buildings, ships, and railroads, to dig mine shafts and redirect rivers to into complex hydraulic mining rigs, to erect dams and dig canals for cities and farms.

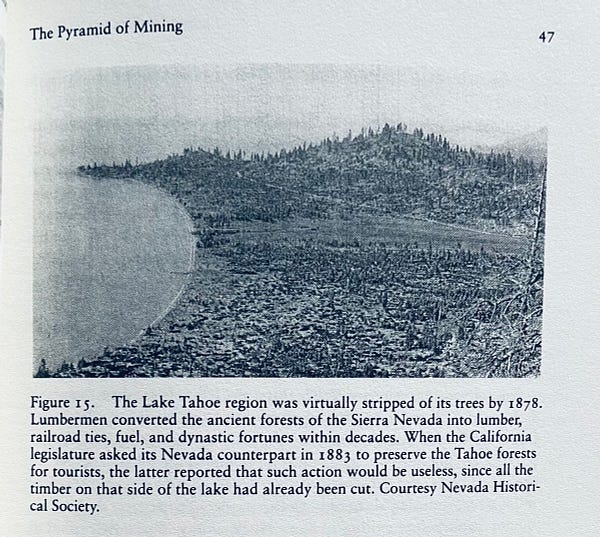

For San Francisco and the surrounding region to be developed, half of California and part Nevada was despoiled and denuded and terraformed. Most forests were cleared, pretty much all the redwoods cut down, rivers were drained, mountains were reduced to mud, animals and birds hunted to extinction — whole ecosystems wiped off the map. That’s how this city was built — on the destruction and plunder of the natural world — not to mention the genocide of the local California Indian tribes. It’s easy to miss the signs of this destructive process because we no longer have a frame of reference to how things used to be. Much of the “nature” that exists now is stuff that grew back after the big clearing took place.

One I dipped into Imperial San Francisco is its focus on water — water and real estate. There would be no city here and no surrounding suburbs, no food, no rising rents, no Silicon Valley high-tech hubs populated by imperial outfits like Lockheed Martin and Google and Facebook — not without draining every surrounding watershed and piping it to San Francisco.

At first this water system was built and owned by an private water monopoly, the Spring Valley Water Company. Then, starting in the early 20th century, it was carried out by the city itself. These dams and aqueducts and reservoirs killed off entire ecosystems and transformed the natural world — all so that a few speculators who got rich off the Gold and Silver Rush and snapped up San Francisco’s barren soil could turn a grim sand dune into a wet and lush environment. Lawns, lush parks — that’s what these Anglo-Saxon types were used to and that’s what they needed to recreate in order to lure the masses and make their speculative land holdings pay off. Brechin writes that after the Central Park was built in Manhattan adjacent property had increased by 1,000 percent in just a few years. That’s what they wanted here, too. And that’s what they built — an ersatz ecosystem that superficially mimicked Central Park and the wet climate of where most of these new settlers had come from: the Atlantic Coast, England.

If you’ve ever been to Golden Gate Park you know they succeeded. But to do it, they needed to drain water from all over the Bay Area and beyond. At some point the city wanted to drain Lake Tahoe. Instead, it got to dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley in a supposedly protected Yosemite National Park.

They doing this alone out here in California. The founding speculators of Los Angeles did the same thing — they plundered water from a distant countryside to fuel their plans for suburban sprawl. That’s what the plot of Polanki’s Chinatown is all about.

How much does San Francisco need to drain in order to maintain its fake lush ecosystem?